The United States has far higher maternal and infant mortality rates compared to other high-income nations, and stark geographic and racial/ethnic disparities. Timely, high-quality data on the factors contributing to poor and inequitable maternal-infant outcomes is critical for developing and evaluating interventions to address this longstanding public health crisis.

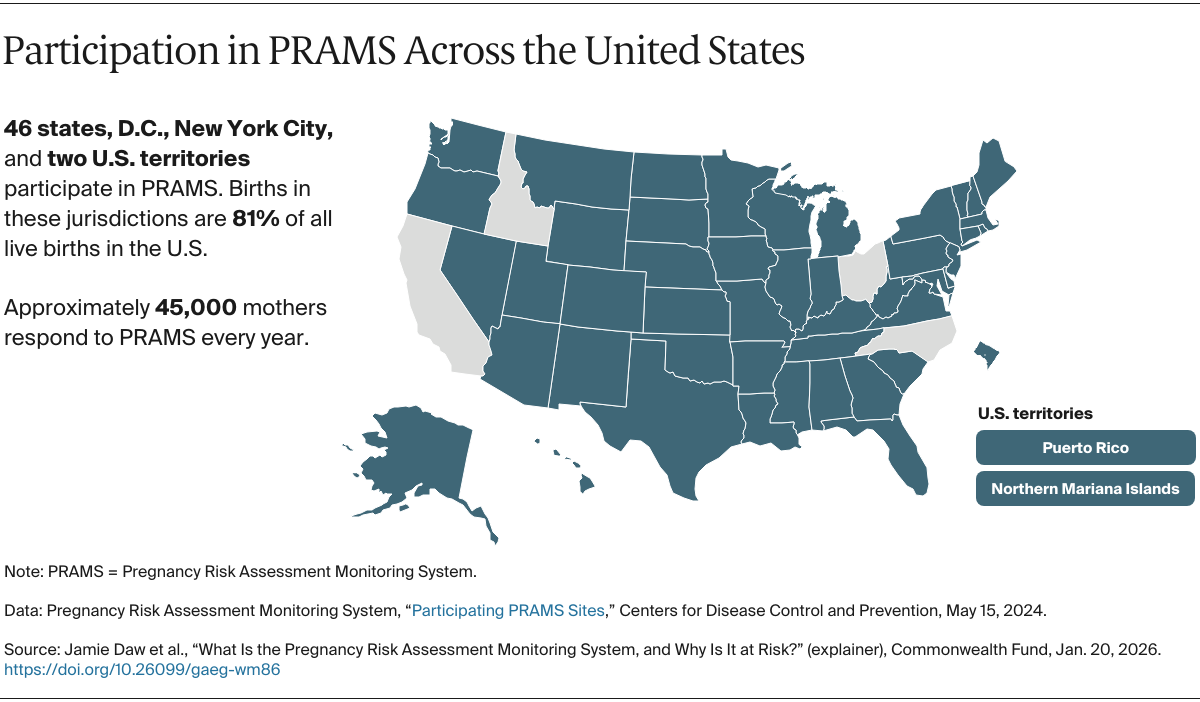

One key source of such data — the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) — is under threat. PRAMS, which is led by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in collaboration with state and city health departments, plays a crucial role in the health of U.S. mothers and babies. By collecting information directly from mothers on maternal health, health behaviors, and experiences before, during, and after pregnancy, PRAMS helps public health experts and policymakers understand what is and isn’t working when it comes to pregnancy and infant care.

PRAMS has been credited with improving maternal health efforts and helping to reduce infant deaths in the U.S., which went from 10 per 1,000 live births in 1987, when the program began, to 5.5 per 1,000 by 2022. However, the shutdown of the PRAMS data collection system in January 2025, and staff reductions at the CDC in April 2025, have led to uncertainty about future funding and data access. Without PRAMS, policymakers and health systems are losing critical data for addressing health disparities and improving maternal and infant health outcomes nationwide.

How does PRAMS support efforts to improve maternal and infant health?

PRAMS has been foundational in supporting the field of maternal-child health research in the U.S., generating hundreds of published studies and successful public health initiatives, including breastfeeding initiatives in both Tennessee and Michigan and a folic acid education campaign in Vermont. PRAMS data have also been integral to the development of programs to improve maternal health. Examples include Asabike Health Start, which provides in-home support to Native American mothers in Michigan, and a pilot program for dental care outreach to pregnant Medicaid enrollees in Connecticut.

States also use PRAMS data extensively when designing policies. In Maine, it informed changes to Medicaid policy, including reimbursement for smoking cessation treatment and extended postpartum coverage, along with public awareness campaigns on shaken-baby syndrome and lead paint risks. In New Jersey, a PRAMS analysis on the root causes of infant mortality among Black families led the state’s Department of Health commissioner to channel $4.7 million to community-based case management programs. Nearly 50,000 women have received case management services as a result, and 25,000 have been referred to home visiting and Healthy Start programs. This funding was also used to hire 79 doulas, 30 maternal-child community health workers (CHWs), and 13 CHW supervisors.

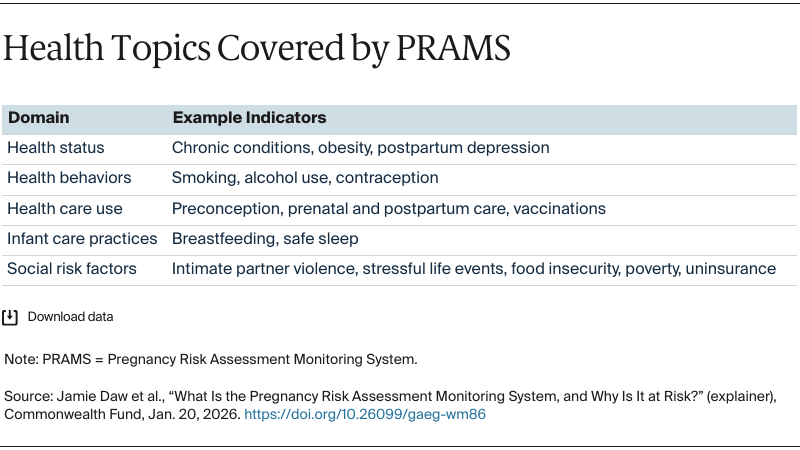

What kind of data does PRAMS collect?

The national Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System tracks maternal health, health behaviors, and experiences before, during, and after pregnancy. Led by the CDC in collaboration with state and city health departments, PRAMS has collected survey information from thousands of mothers across the country every year since its launch in 1987. Topics include prenatal care, pregnancy experiences, birth outcomes, and health behaviors. Surveys may be conducted by mail, online, or via telephone. This information helps researchers and policymakers understand the factors that affect maternal and infant health and identify trends, disparities, and emerging issues of concern.