This brief was originally published in December 2020 and updated in July 2025.

A mother, who does not wish to be named, holds her baby in their home on February 2, 2023, in Houston. The COVID-19 pandemic only deepened the racial disparities in pregnancy-related deaths that existed prior to 2020. Photo: Jahi Chikwendiu/Washington Post via Getty Images

A mother, who does not wish to be named, holds her baby in their home on February 2, 2023, in Houston. The COVID-19 pandemic only deepened the racial disparities in pregnancy-related deaths that existed prior to 2020. Photo: Jahi Chikwendiu/Washington Post via Getty Images

Behavioral health issues, including drug use, were the leading cause of maternal deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic, accounting for one-fifth of those deaths

Maternal death rates are 18 percent to 49 percent higher in states that haven’t expanded Medicaid eligibility compared to states that have

Behavioral health issues, including drug use, were the leading cause of maternal deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic, accounting for one-fifth of those deaths

Maternal death rates are 18 percent to 49 percent higher in states that haven’t expanded Medicaid eligibility compared to states that have

This brief was originally published in December 2020 and updated in July 2025.

In 2023, at a time when maternal mortality was declining worldwide, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the United States was one of only seven countries to report a significant increase in the proportion of pregnancies that result in the death of the mother since 2000. The other countries are Venezuela, Cyprus, Greece, Mauritius, Belize, and the Dominican Republic, as well as the U.S. Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. Maternal deaths in the U.S. had leveled in the years prior to the pandemic, but the maternal mortality ratio is still higher today than in comparable countries, and significant racial disparities persist.

The Commonwealth Fund’s 2025 Scorecard on State Health System Performance revealed that states with the highest maternal mortality rates rank among the worst in overall health system performance. This brief delves deeper into this relationship by highlighting the causes of maternal mortality and its impact on overall health. We draw on a range of recent data sets to describe the state of maternal health in the U.S. today. While there are multiple systems for measuring maternal mortality, we relied whenever possible on estimates published by the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System (PMSS), maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (For more details, see “How We Conducted This Study.”)

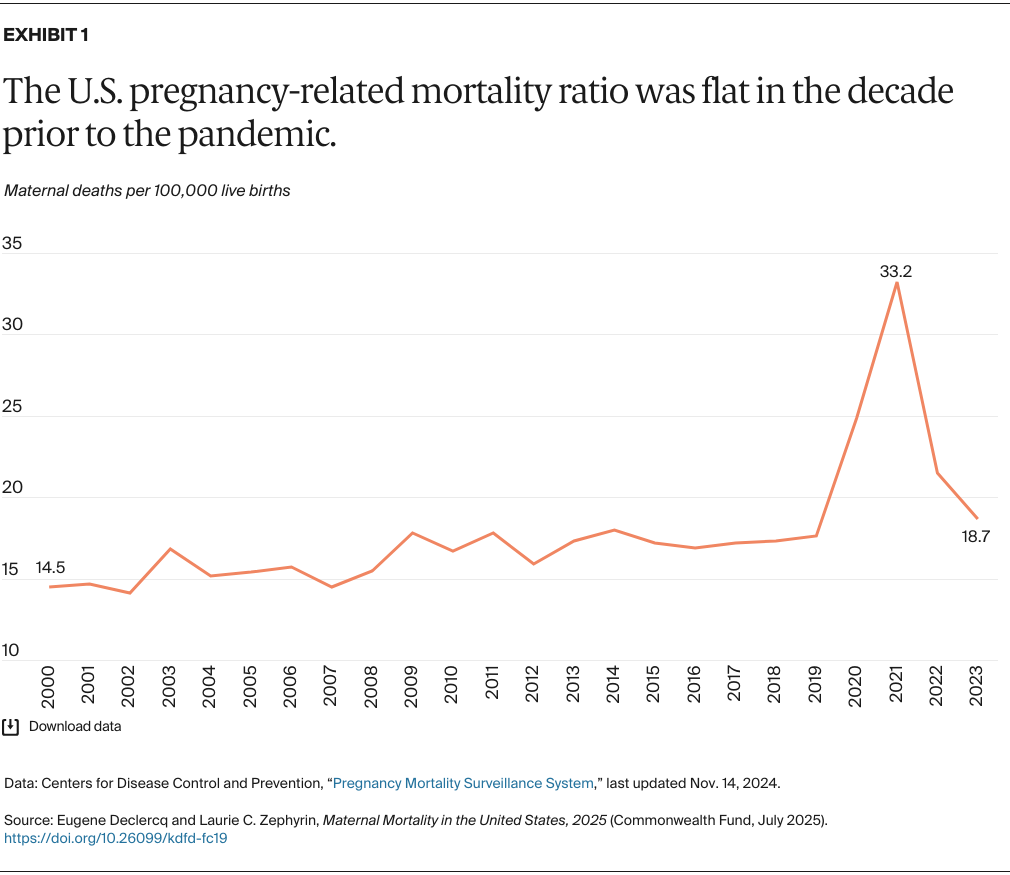

The pregnancy-related mortality ratio increased by 22.8 percent between 2000 and 2009 before stabilizing at about 660 deaths a year. That changed between 2019 and 2021, when the number of deaths almost doubled, to 1,222, largely because of the COVID-19 pandemic. By 2023 the ratio had almost returned to its prepandemic level, dropping back to 676 deaths — similar to the earlier totals, although the number of births has continued to decline. While Exhibit 1 suggests less change in maternal deaths over time than past media reports indicate, even this more conservative measure would place the U.S. last among high-income countries, with a mortality ratio triple that of Sweden, Japan, the Netherlands, Germany, the United Kingdom, and France.

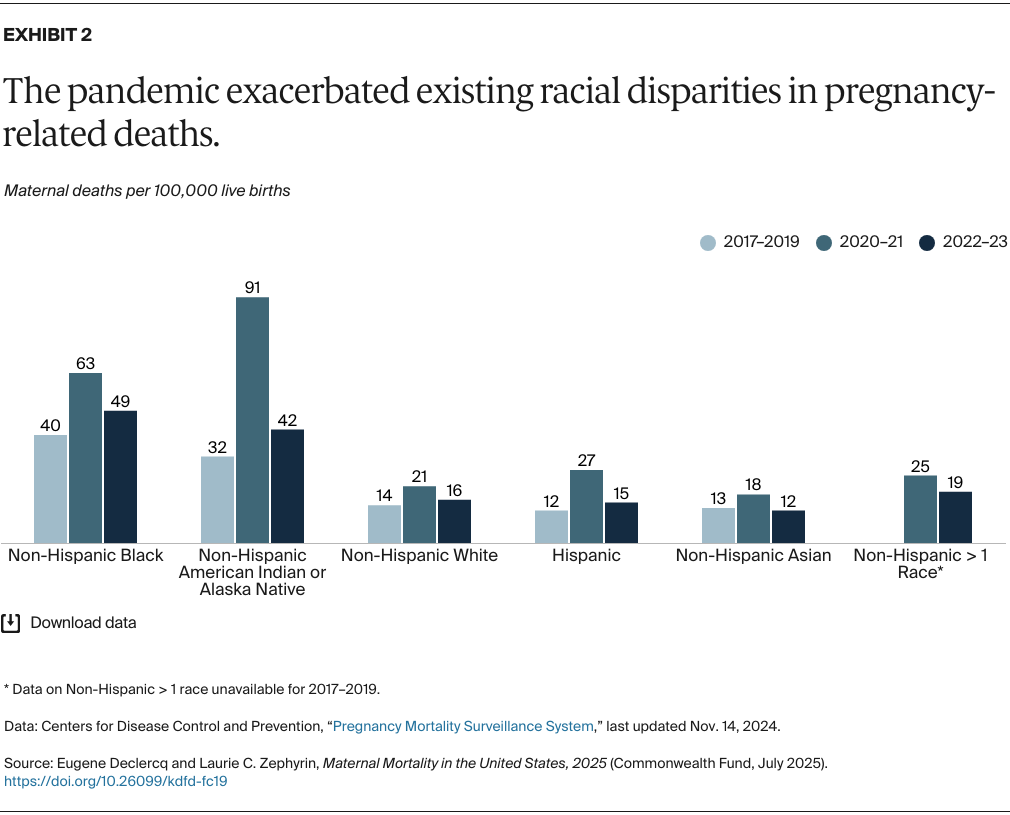

The COVID-19 pandemic only deepened the racial disparities in pregnancy-related deaths that existed prior to 2020. Ratios for non-Hispanic Black people and non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native people were far higher than for other groups, both prior to and, especially, during the pandemic (Exhibit 2):

COVID-19 had significant impacts on maternal deaths across the board, with research showing infection with the virus increased risks of pregnancy-related complications. Racial and ethnic disparities in impact were related to differences in rates of infection across different groups and variations in vaccination rates. These differences have been ascribed to disparities in baseline social drivers of health, as lower access to resources, inadequate housing, and environmental and work-related hazards contributed to greater COVID exposure.

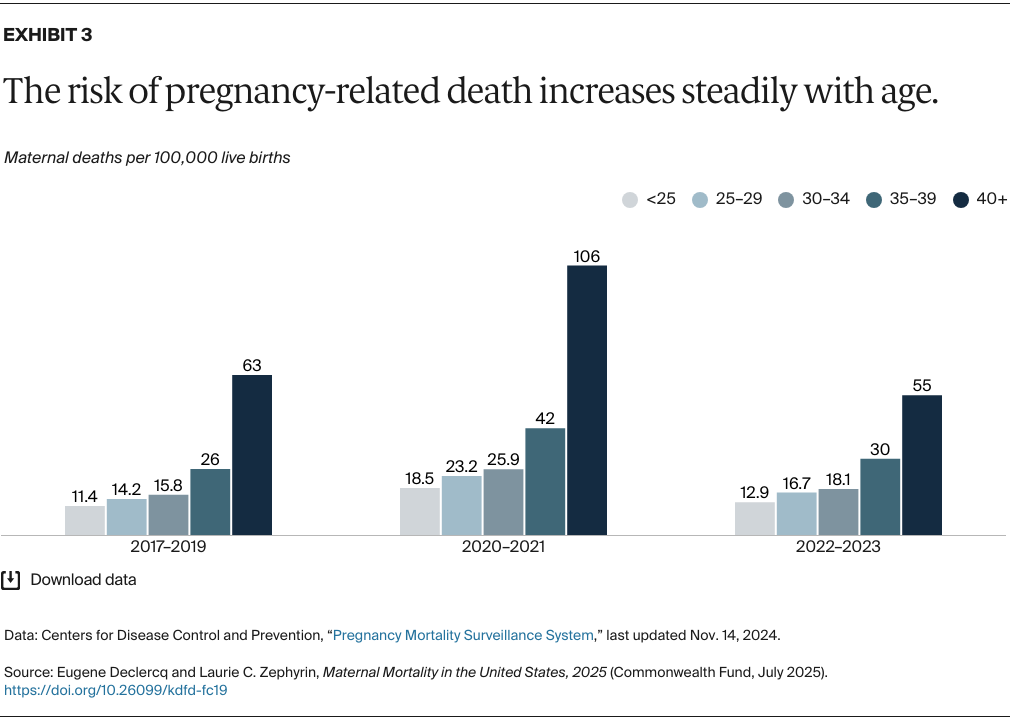

The pregnancy-related death ratio increased across age groups in each of the periods studied. A familiar pattern is seen: a surge in deaths during the pandemic followed by a sizable decrease in 2022–2023, though not to prepandemic levels (Exhibit 3). While there are steady increases across all age groups, pregnancy-related death ratios were at least 80 percent higher for those age 40 and older than those ages 35–39 in each time period. Pregnancy-related death ratios for those age 40 and older reached 106.3 during the pandemic.

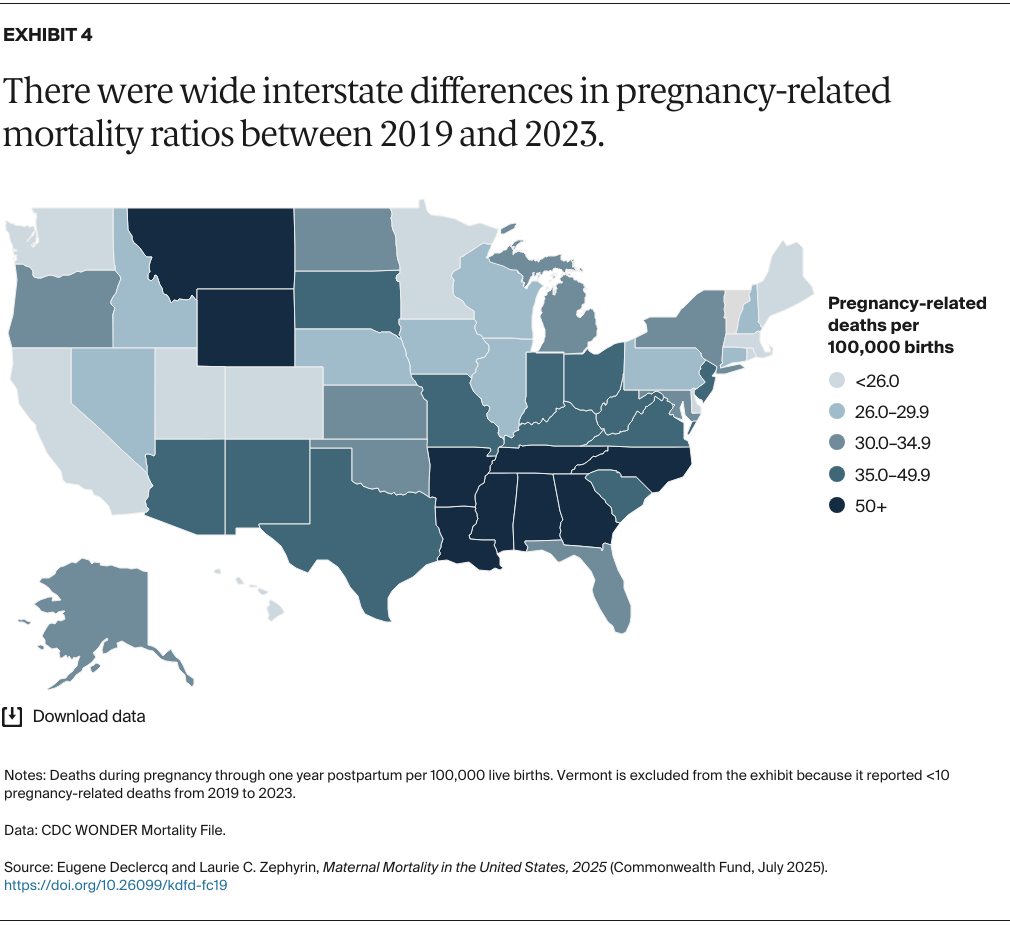

States in the Deep South report higher pregnancy-related death ratios, while states in the Northeast and West report lower ratios (Exhibit 4). (Note: Since the CDC’s PMSS reports data by region only, we looked to the National Vital Statistics System database to obtain comparisons among states.) Six states — California, Colorado, Delaware, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Utah — reported a ratio of pregnancy-related deaths of less than 25 per 100,000. Meanwhile, Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, North Carolina, Tennessee, Wyoming, and the District of Columbia all had rates at least twice that high.

Historically, the Deep South has invested less in maternal health and experienced poorer maternal and infant health outcomes than other areas of the U.S. For example, few states in the region have expanded Medicaid eligibility, and little has been done to address the widespread impact of hospital obstetric unit closures.

In addition, rural areas of the U.S. have a disproportionate number of maternity care deserts — areas with no or limited access to maternal health services — and lack sufficient workforce capacity and investment. (See Exhibit 8 for more on this.)

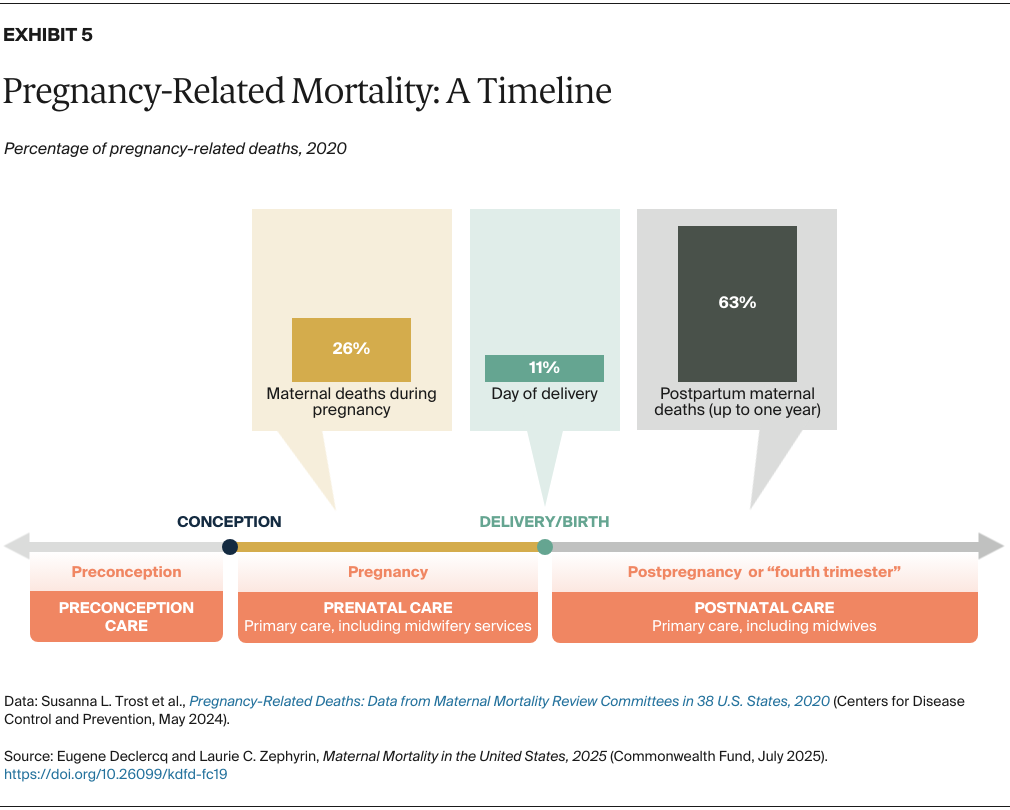

A significant development in our understanding of pregnancy-related deaths occurred in 2015, when the CDC began presenting these deaths by when they occurred across the 21-month period between conception and one year after birth (Exhibit 5). In 2020, only 11 percent of deaths occurred on the day of delivery, with the majority of deaths — 63 percent — happening in the first year postbirth.

While efforts are underway to improve clinical care at the time of birth, comprehensive solutions to prevent maternal deaths must ultimately involve health care systems, community-based birth and maternity care systems, policymaking, and clinical and social interventions before, during, and after pregnancy. One example of a policy response is the extension of Medicaid eligibility for pregnant women up to a year postpartum (see Exhibit 15). With most maternal deaths and morbidity occurring in the year after birth, it’s especially important to ensure that women have adequate health care coverage and that there are consistent standards of care during this time.

Comprehensive care in the postpartum period also requires integrated family care for mother and baby, efforts to ensure social needs are met, and treatment of mental health issues.

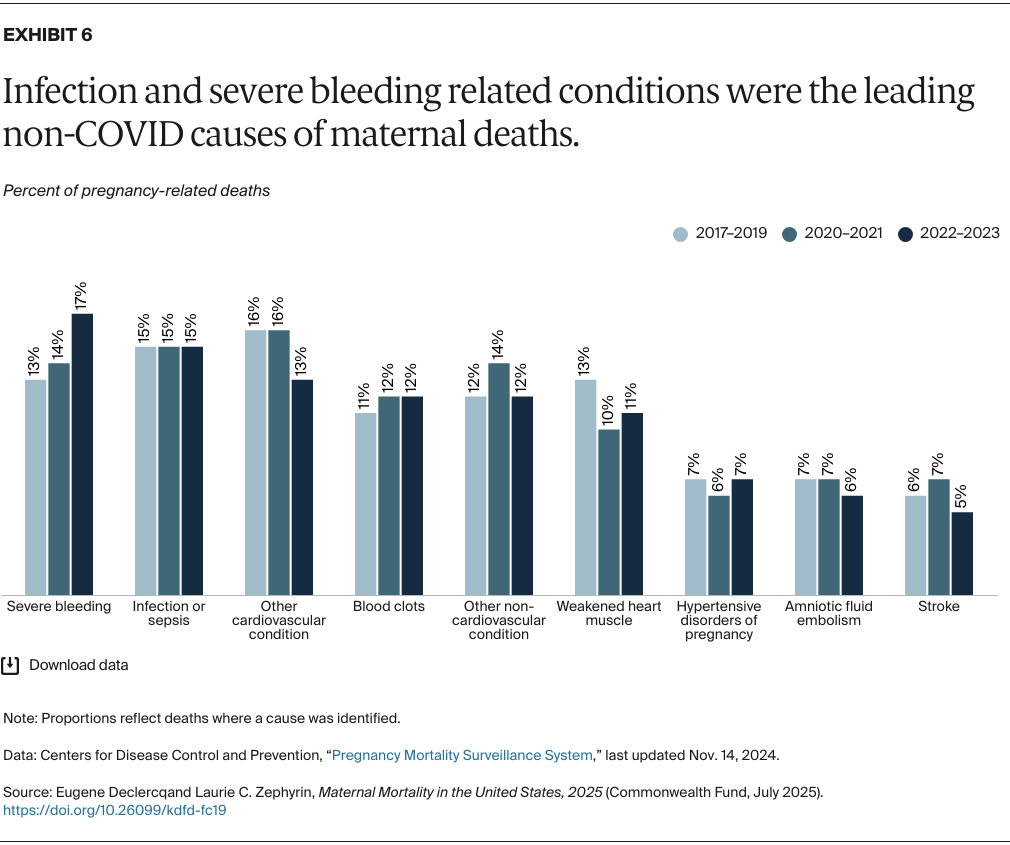

Since the massive surge in COVID-19 deaths in 2020–2021 can overwhelm the comparison of causes of death over time, Exhibit 6 is limited to non-COVID causes. Severe bleeding (hemorrhage) increased notably during this period, accounting for roughly one in six deaths by 2022–2023, while non-COVID infections now cause about one in seven maternal deaths.

Cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension-related complications, and cardiomyopathy (weakened heart muscle), contribute to the leading causes of pregnancy-related death. Mortality and morbidity from these complications are mostly preventable; eliminating disparities in treatment, experience, and outcomes is critical to addressing this problem.

What these data do not present are deaths associated with mental health and substance use. For those, we turn to the next exhibit, which is based on data from maternal mortality review committees.

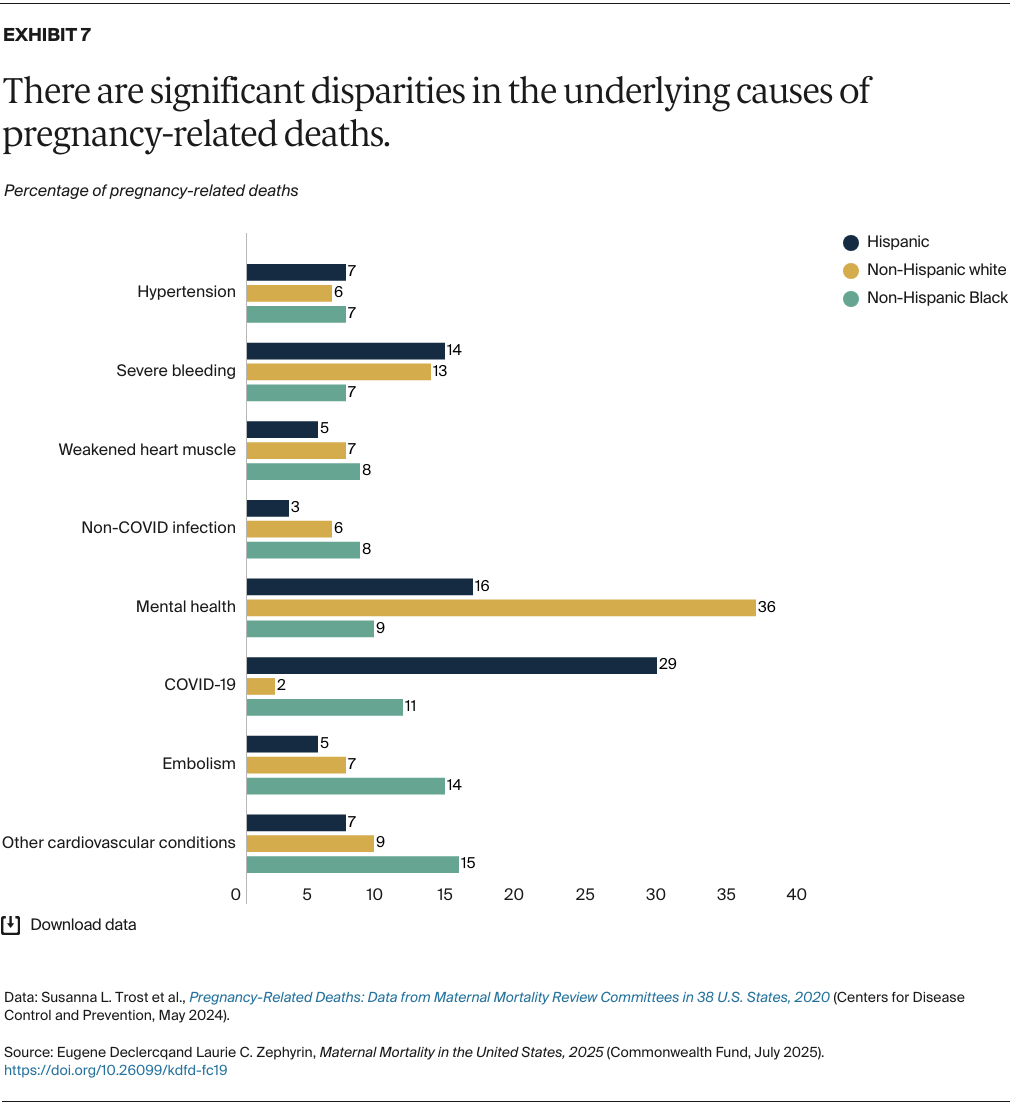

In contrast to the CDC data presented in the previous exhibit, state maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) include more underlying causes of death and more granular data by race and ethnicity. MMRC data reveal that four times the proportion of non-Hispanic white women died as a result of mental health issues in pregnancy, including substance use conditions, compared to non-Hispanic Black women, and more than twice the proportion compared to Hispanic women (Exhibit 7). Additionally, white women experienced almost double the proportion of deaths from severe bleeding compared to Black women.

Pregnant non-Hispanic Black women were far more likely to die from cardiac-related conditions, COVID-19, and embolisms. Pregnant Hispanic women died at much higher rates from COVID than either other group — and the 2020 data in Exhibit 7 don’t capture the full force of the pandemic in 2021.

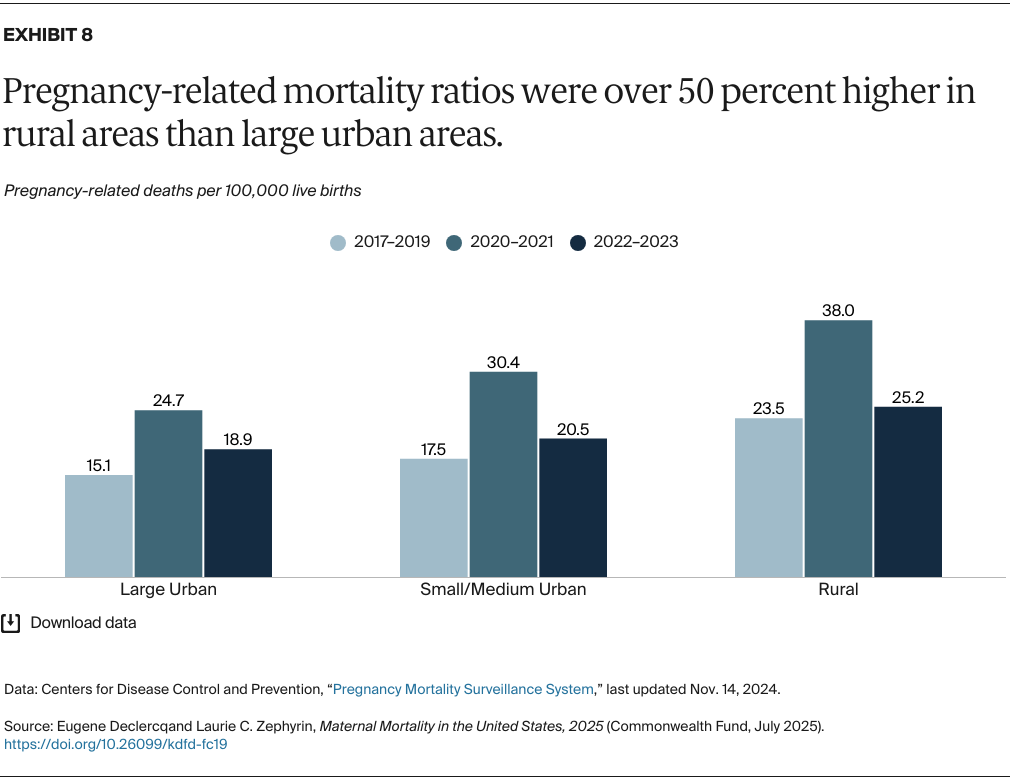

Maternal deaths have long been more likely to occur in rural areas compared to urban areas, with the former more than twice as likely to lack an obstetrician. Mortality ratios in rural areas were over 50 percent higher than in large urban areas (Exhibit 8), though following the pandemic that difference dropped to 33 percent. During the pandemic, pregnancy-related death ratios increased by 74 percent in small-to-medium metro areas, 64 percent in large metro areas, and 62 percent in rural communities (where they were already high). Postpandemic mortality ratios declined in all settings, but especially in rural areas where ratios approached prepandemic levels.

Rural residents were already more likely to be living in a maternity care desert. Rural areas also have a large proportion of women without health insurance. The pandemic further impeded access to hospital maternity care.

Workforce shortages, obstetrical unit closures, and transportation barriers in rural communities also contribute to the disparities observed. Even urban areas, which have greater access to providers, reported significant gaps in care, with 24 percent having no clinical obstetrician.

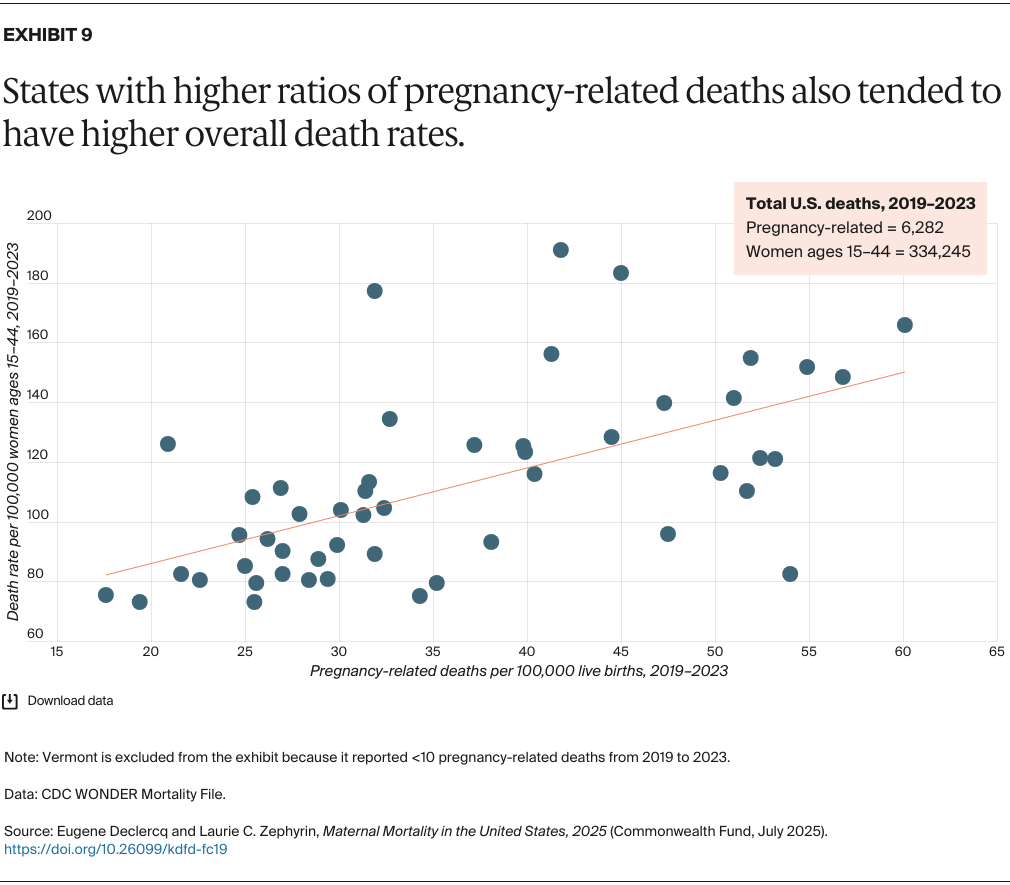

While maternal deaths account for less than 2 percent of all deaths for women of reproductive age, state-level pregnancy-related mortality ratios between 2019 and 2023 broadly mirror their overall death rates (Exhibit 9). This suggests that there is also an overall crisis in avoidable deaths among women of reproductive age. So while there were 6,282 pregnancy-related deaths in the five-year period, a total of more than 334,000 women of reproductive age died during this time.

States with the highest pregnancy-related death ratios — Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee — also have high overall death rates for women ages 15 to 44. Meanwhile, states with low overall female death rates, like California, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Utah, also have low pregnancy-related mortality. Thus, a singular focus on pregnancy-related mortality may obscure the strong link (r =+.59; a perfect relationship would be 1.00) between maternal health and overall women’s health.

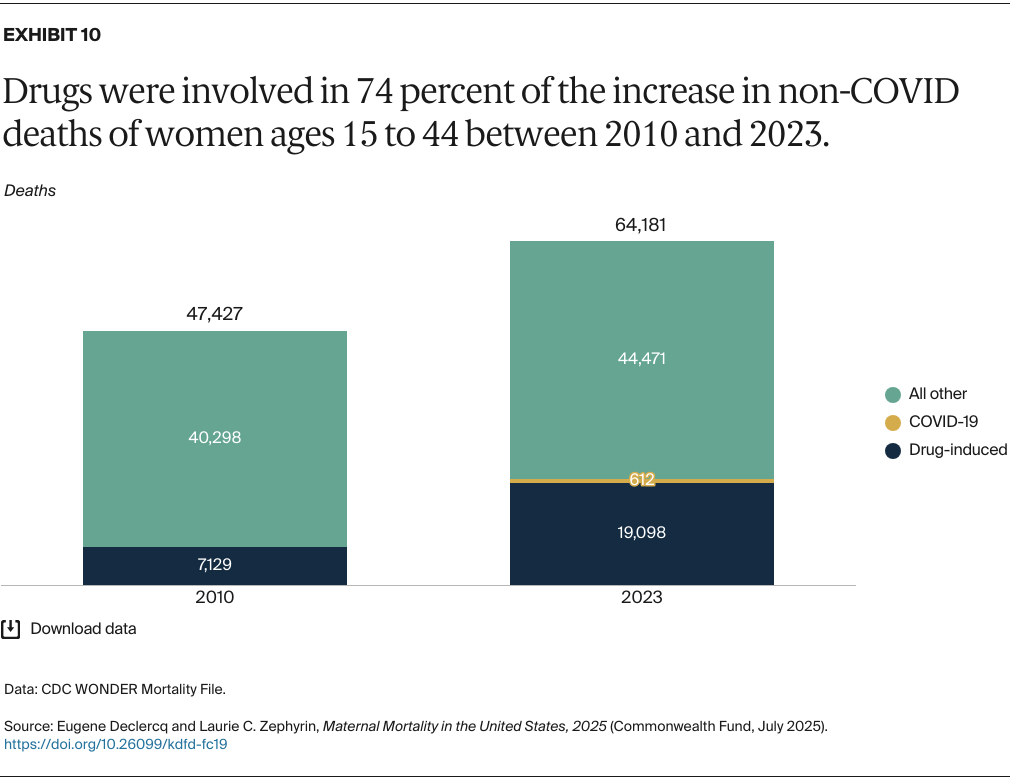

After excluding COVID-related deaths, more than 16,000 more women of reproductive age died in 2023 compared to 2010 (Exhibit 10). Nearly three-quarters (11,969 of 16,142) of this increase in deaths were due to “drug induced” causes — defined by the CDC as unintentional drug overdoses, suicides, homicides, or undetermined. This suggests that drug abuse is a major challenge facing women overall, not just those who are pregnant.

Two in five pregnancy-related deaths in 2021 were attributed to COVID. The profound impact of the pandemic is evident in the rise in pregnancy-related deaths from 664 to 1,222 between 2018 and 2021 (Exhibit 11). Notably, during the height of the pandemic between 2020 and 2021, the number of non-COVID pregnancy-related deaths increased, perhaps reflecting the pandemic’s strain on health resources. By 2023, COVID accounted for only eight pregnancy-related deaths, and overall totals had returned to their earlier plateau.

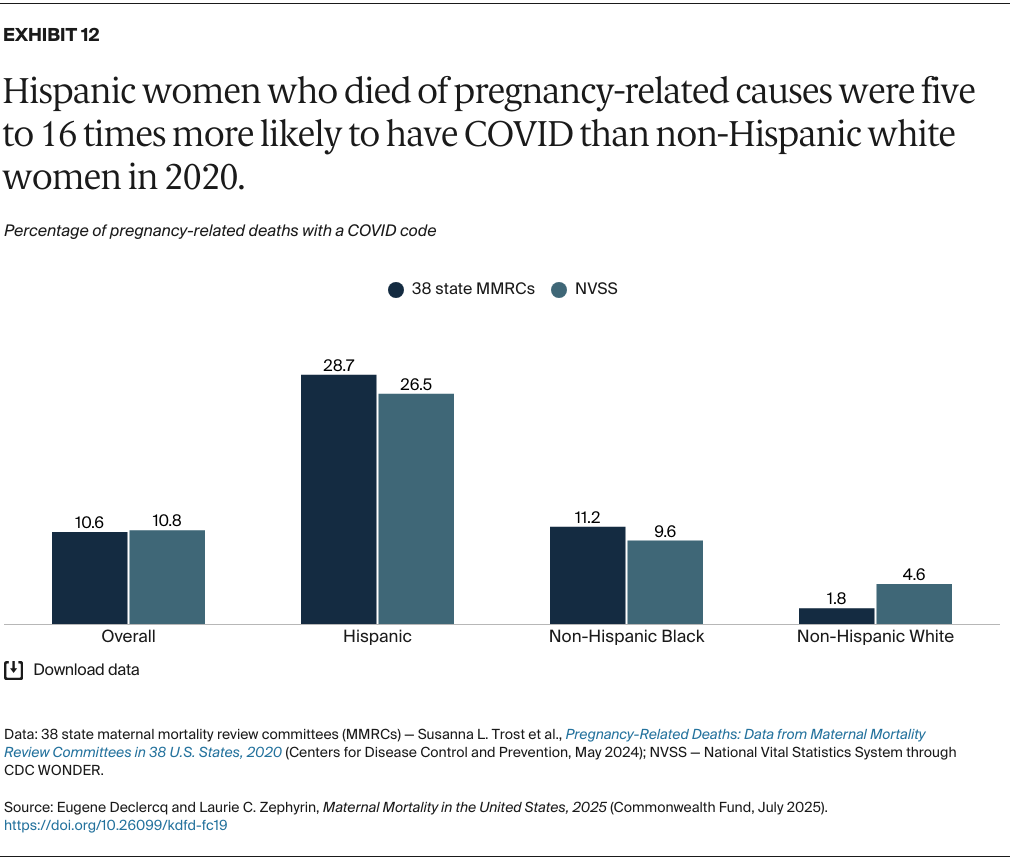

The pandemic had a disproportionate impact on U.S. communities of color. The impact on Hispanic communities was exceptional: even studies relying on completely different data sources — a report drawing from 38 state MMRCs and the National Vital Statistics System — show remarkably similar findings.

Overall, about 11 percent of pregnancy-related deaths were associated with COVID-19 in 2020, but these two different sources both show that over a quarter of pregnancy-related deaths among Hispanic women were linked to the disease (Exhibit 12). In the MMRC data, which identify the primary cause of death, the proportion of deaths from COVID-19 was nearly 16 times higher (28.7% to 1.8%) for Hispanic people than for those identifying as non-Hispanic white. (The number of pregnancy-related deaths associated with COVID-19 for non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Natives and non-Hispanic Asians were too few to be reported here.)

Factors contributing to these disparities in COVID-related deaths include significantly lower COVID vaccination rates early in the pandemic, vaccines initially not being recommended for pregnant women, the higher proportion of multigenerational households, and the greater concentration of “essential workers” in Hispanic/Latino communities. For policymakers preparing for future pandemics, the social drivers of health and racial disparities are key issues to address.

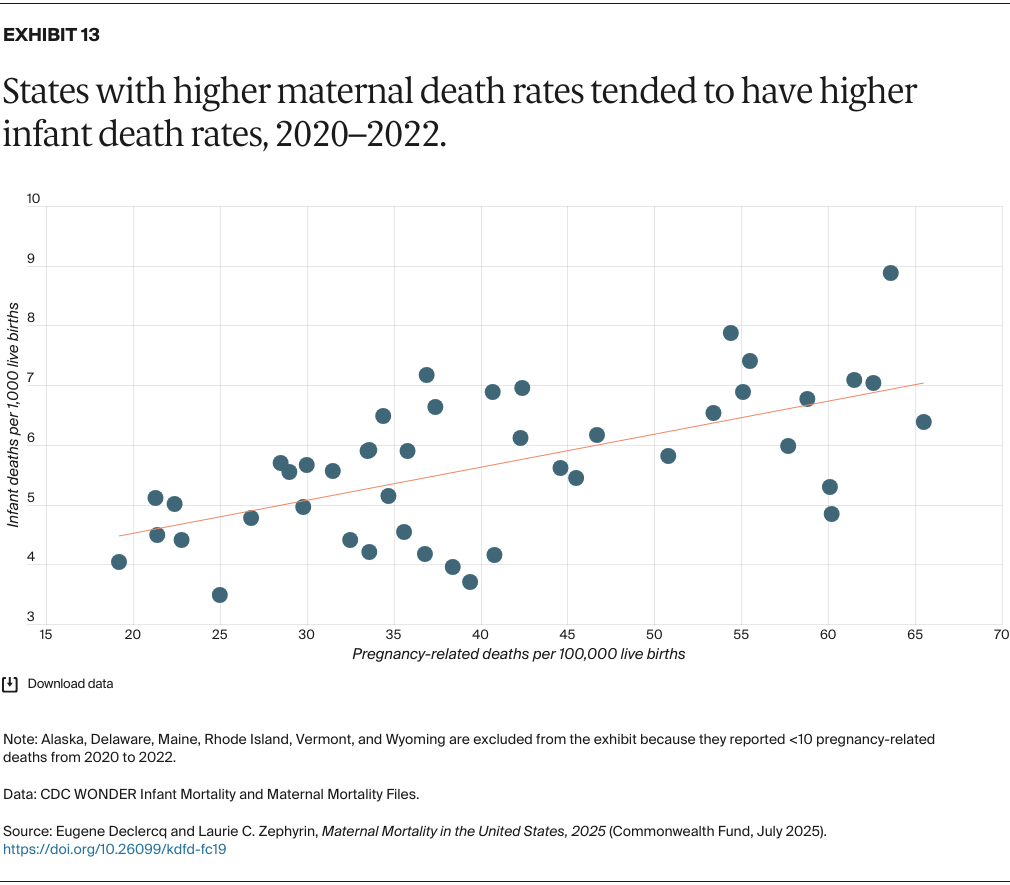

There is a strong relationship between maternal and infant mortality that reaffirms the inextricable link between the health of mother and baby. Exhibit 13 presents data on maternal deaths out to one year postpartum in the 45 states with at least 10 deaths from 2020 through 2022. States with high rates of pregnancy-related mortality, such as Alabama, Mississippi, South Dakota, and Tennessee, also have high rates of infant mortality. States with low mortality rates like California, Minnesota, and Washington fare better on both outcomes. The strong positive statistical correlation (r =+.61; a perfect relationship would be 1.00) serves as a familiar reminder that maternal health and infant health cannot be separated.

Although overall U.S. infant mortality rates had been declining prior to COVID, these rates spiked during the pandemic. The increases resulted from a number of issues, including restricted access to health care, the greater impact of respiratory viruses, and the effects of geographic and racial disparities.

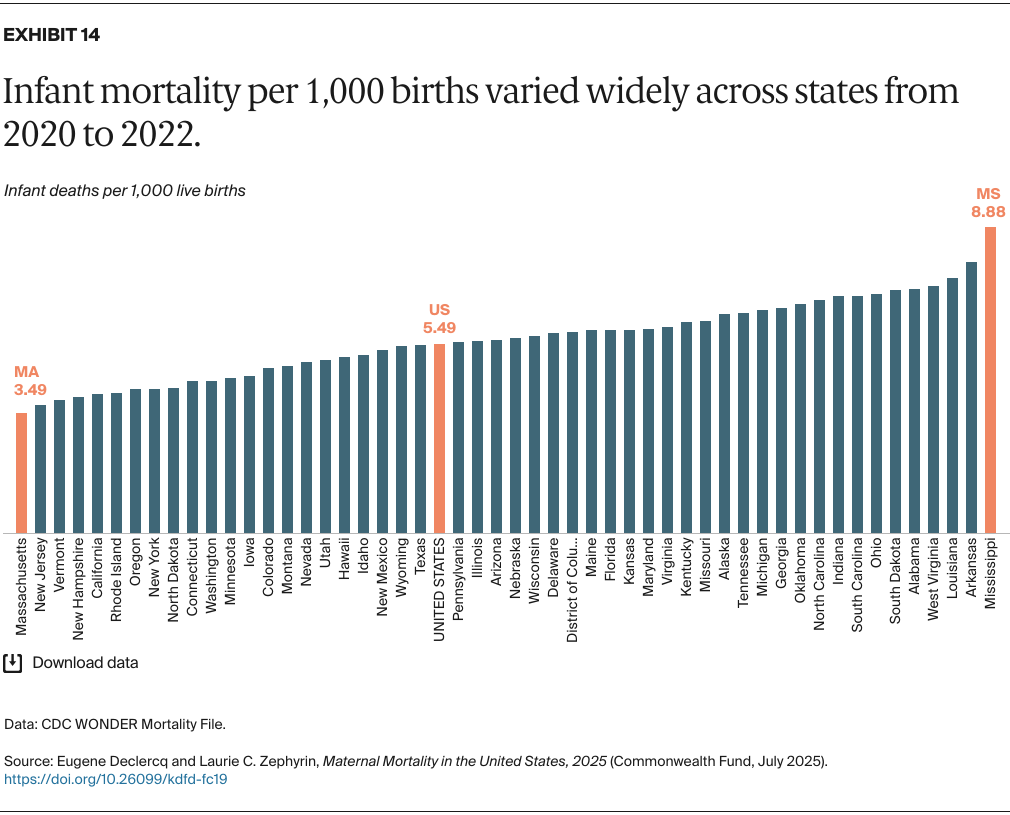

Infant mortality rates vary widely across the U.S., with the worst-performing state, Mississippi, having more than double the rate of the 11 top-performing states (Exhibit 14). As is the case with pregnancy-related mortality, southern states generally had the highest infant death rates; only Texas has an infant mortality rate comparable to the national average.

Eligibility for Medicaid coverage varies widely across states, as 10 states (those shown in orange in Exhibit 15) have opted not to expand Medicaid eligibility as provided under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Studies demonstrate that Medicaid expansion has improved health outcomes and narrowed disparities.

But also critically important is the extension of Medicaid’s postpartum coverage. With the recognition that a large share of maternal deaths occurs following birth, there has been growing bipartisan momentum to extend the 60-day cutoff to one year. Today, nearly all states have extended Medicaid coverage to one year postpartum. Some of these extensions are time-limited, however, and could lapse without renewed federal or state action. Preserving Medicaid coverage and enhanced postpartum coverage is critical to addressing the maternal health crisis.

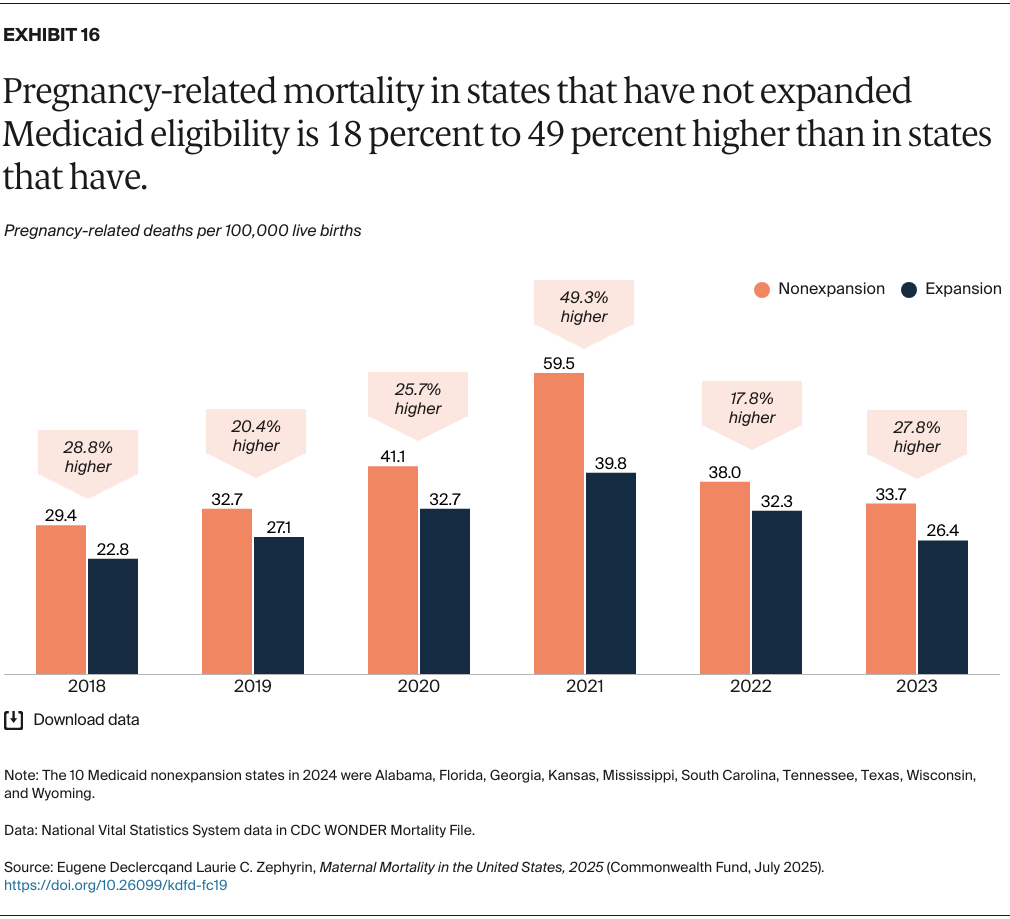

States that have not taken up the ACA’s Medicaid eligibility expansion have consistently reported higher rates of pregnancy-related mortality than those that have. The differences sharpened during the pandemic, particularly in 2021, when pregnancy-related mortality rates were 49 percent higher in nonexpansion states compared to states that had expanded (Exhibit 16).

A similar comparison (not shown) of infant deaths finds nonexpansion states averaging a 23 percent higher infant mortality rate than states that expanded access to Medicaid. Not expanding Medicaid in these states has had a profound impact on death rates for some of the most vulnerable individuals.

In the four years since the 2020 edition of this brief, which analyzed data through 2016, there have been many efforts to better monitor and prevent maternal deaths. Measurement has been notably improved by increased support for state maternal mortality review committees: their regular issuance of state reports has provided localized recommendations for interventions to prevent further deaths. Federal and state government efforts to improve maternal health have also been critical, including efforts to expand Perinatal Quality Collaboratives to establish clinical and public health programs.

Access to maternal and reproductive health care, however, is under threat. Federal budget cuts have the potential to worsen maternal and infant mortality and widen racial and regional disparities. Moreover, the declining availability of federal data could undermine the ability to track the impacts of these policy choices.

Maternal deaths are closely related to infant mortality and deaths of women of reproductive age overall. As such, there’s a need to also address overall perinatal health before, during, and after pregnancy and the impact of disparities by race, ethnicity, and geographic region.

Sharp geographic differences in maternal and infant deaths persist. In particular, the data show higher ratios of pregnancy-related mortality in rural areas compared to urban areas, with even wider disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Closures of rural hospitals and maternity wards, which have left many communities with no facilities or maternity providers to help with birthing, are one possible reason. Women in rural communities have worse health outcomes overall compared to their nonrural counterparts as well as limited access to behavioral health care to address substance use during pregnancy and beyond. Additional studies highlight more limited access to obstetric services in rural communities with a high proportion of Black residents.

MMRCs identified behavioral health issues, which include substance use, as the leading cause of maternal deaths overall, accounting for more than one-fifth of these deaths. Perinatal depression has been the subject of multiple efforts at the state level with the passage of laws typically requiring screening and education. More challenging is the need to enhance the mental health workforce so there is a sufficient number of trained providers. As we noted, substance use–related deaths accounted for most of the increase in deaths of women of reproductive age since 2010 — addressing this problem requires extensive public and private investment in both prevention and treatment.

We saw a large increase in maternal deaths across all racial groups during the pandemic, with the largest increases among Black and Native American people. Hispanic people, who historically had lower pregnancy-related mortality rates, experienced an increase in COVID-related deaths several times larger than other groups. This is consistent with COVID-19 disparities: Black and Hispanic people died at higher rates and younger ages from COVID-19 than their white counterparts, even when controlling for preexisting conditions. This signals the need to address underlying social drivers of health, such as income, employment, and health care access, that systematically disadvantage communities of color.

Increasing health insurance coverage, including through the Medicaid eligibility expansion and the adoption of one-year postpartum Medicaid coverage, is a crucial element in addressing the maternal health crisis. Equally important is the vigorous response of the clinical and public health communities. Their ongoing efforts include the Alliance for Improved Maternity Care’s best practices for treatment of critical conditions like sepsis and postpartum hemorrhage; the establishment of community-based birthing centers, which can offer culturally sensitive perinatal care teams that include midwives and doulas; and policy initiatives to support expanded perinatal services. Efforts to address causes of racial and ethnic disparities in access, experience, quality, and outcomes are key as interventions are implemented.

An important lesson from the past five years is that maternal health cannot be viewed separately from the overall health of women and infants, from social needs, and from the impact of disparate access to high-quality and equitable care. For example, we found that overall death rates for women of reproductive age rose faster than maternal deaths, and that substance use was a significant factor. We also found infant mortality was strongly linked to pregnancy-related mortality. Both vary widely across states, suggesting that state policies on Medicaid coverage are related to these outcomes. We also know that there are promising community-led approaches across the U.S. that could help transform maternity care but require sustainable investment to thrive.

The figures cited in this brief are based on data from a wide range of contemporary sources. The overall trend, racial comparisons, the impact of COVID, and breakdowns of maternal death by causes of death are from recently released (May 2025) data from the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System (PMSS) and the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application, both developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The state ratios were published by the CDC’s National Vital Statistics System (NVSS).

The NVSS provides the official reports of maternal mortality, and in 2020, after a decade-long hiatus, reported a national ratio for 2018 (17.4 deaths per 100,000 births). Meanwhile, the CDC has been publishing a pregnancy-related mortality ratio for more than two decades; we used those data to compute longer-term trends. Finally, the CDC has developed the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application system, for which data from states’ maternal mortality review committees are gathered to produce multistate reports on maternal deaths.

The major limitation in examining maternal mortality is that there is no single national system in the United States for collecting maternal mortality data. Rather, there is a federal system wherein deaths are reported at the local and state levels and those reports are conveyed to federal officials. Therefore, the system relies on the quality of data collected locally and the quality-control processes for converting those reports into national data. Documentation and analysis of maternal mortality over time have been hampered by limited funding, changing definitions, and inconsistent reporting by states. These shortcomings have resulted in notable gaps in our understanding of the problem, including the degree of difference in maternal mortality between urban and rural areas — though there is considerable evidence of the growing problem of maternal health service gaps in rural areas.

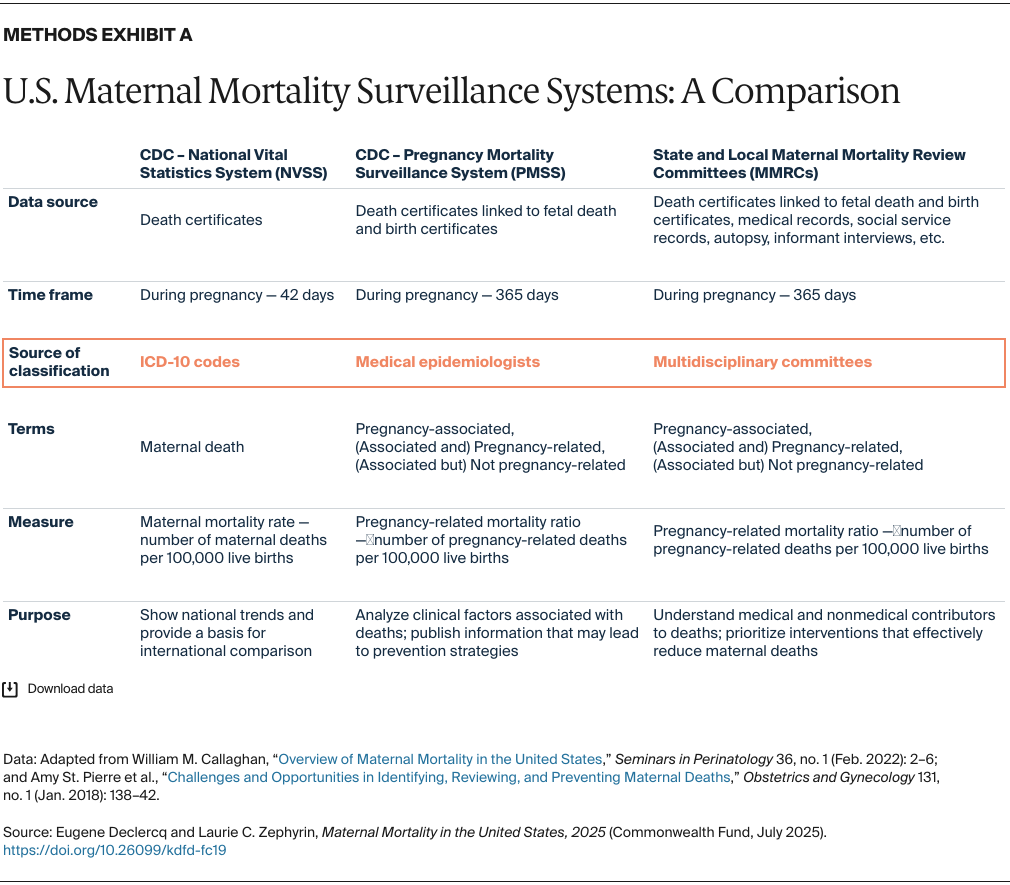

Methods Exhibit A, developed by the CDC, summarizes the differences between the three current systems: the CDC’s NVSS and PMSS, and state and local maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs). Each system has particular strengths and limitations based on the sources used and nature of the analysis of those deaths. Most notably, the NVSS involves maternal deaths during pregnancy and up to 42 days postpartum, an international standard for World Health Organization (WHO) comparisons, while the other two include deaths out to a year postpartum.

The three systems also have different processes by which they classify a death as related to the pregnancy or not, specifically whether to exclude accidental deaths or deaths from conditions not caused by or exacerbated by the pregnancy. In this brief we relied primarily on the PMSS data (pregnancy-related mortality out to a year postpartum), though we drew from all three systems as needed.

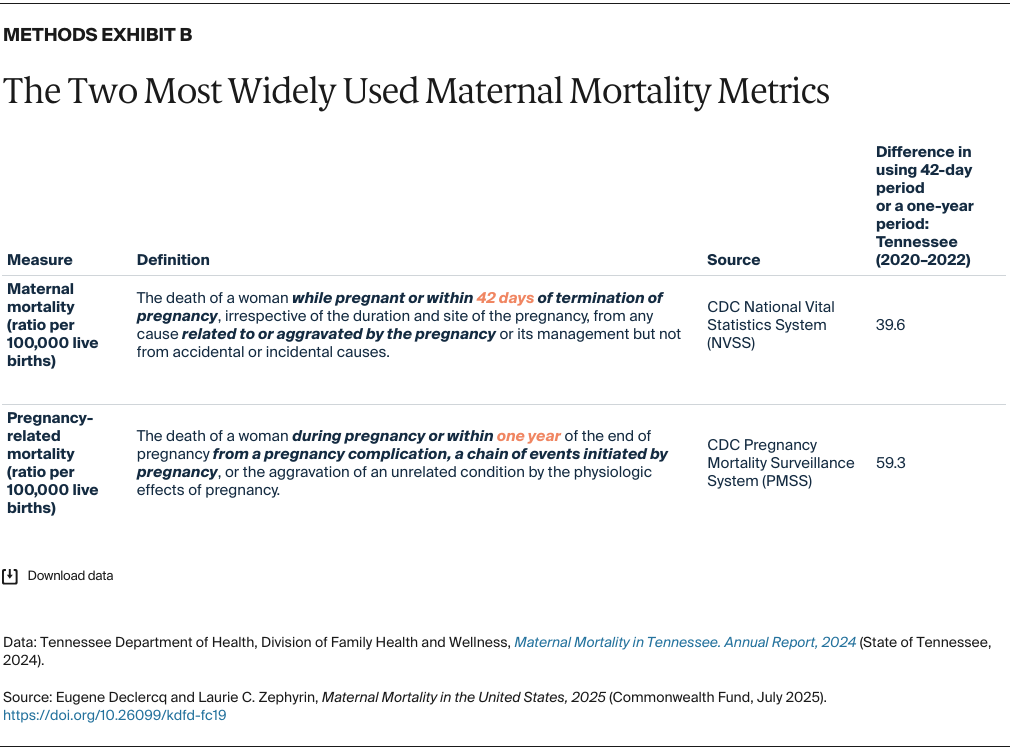

Methods Exhibit B presents the two most widely used measures of maternal deaths: the NVSS Maternal Mortality Ratio and the CDC’s Pregnancy Related Death Ratio. We drew on data from a thorough report from the Tennessee MMRC to illustrate the difference the time frame can make. At least in this state, at this point in time (note this includes the pandemic), extending the time frame to one year added about 50 percent more deaths to the total, a finding that is fairly consistent across states.

The authors thank Juliana Stoneback, M.P.H., and Sarah Christie, Ph.D., M.P.H., for data analytic support on this brief.