Abstract

Issue: Most people with Medicaid who have given birth in the past 12 months are enrolled in Medicaid managed care (MMC), underscoring the essential role state Medicaid agencies and managed care organizations play in ensuring continuous, high-quality postpartum care. Recent federal Medicaid funding cuts, however, pose challenges for postpartum enrollees.

Goal: To explore states’ requirements for postpartum care from their Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) and whether these requirements were expanded after states extended continuous Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum.

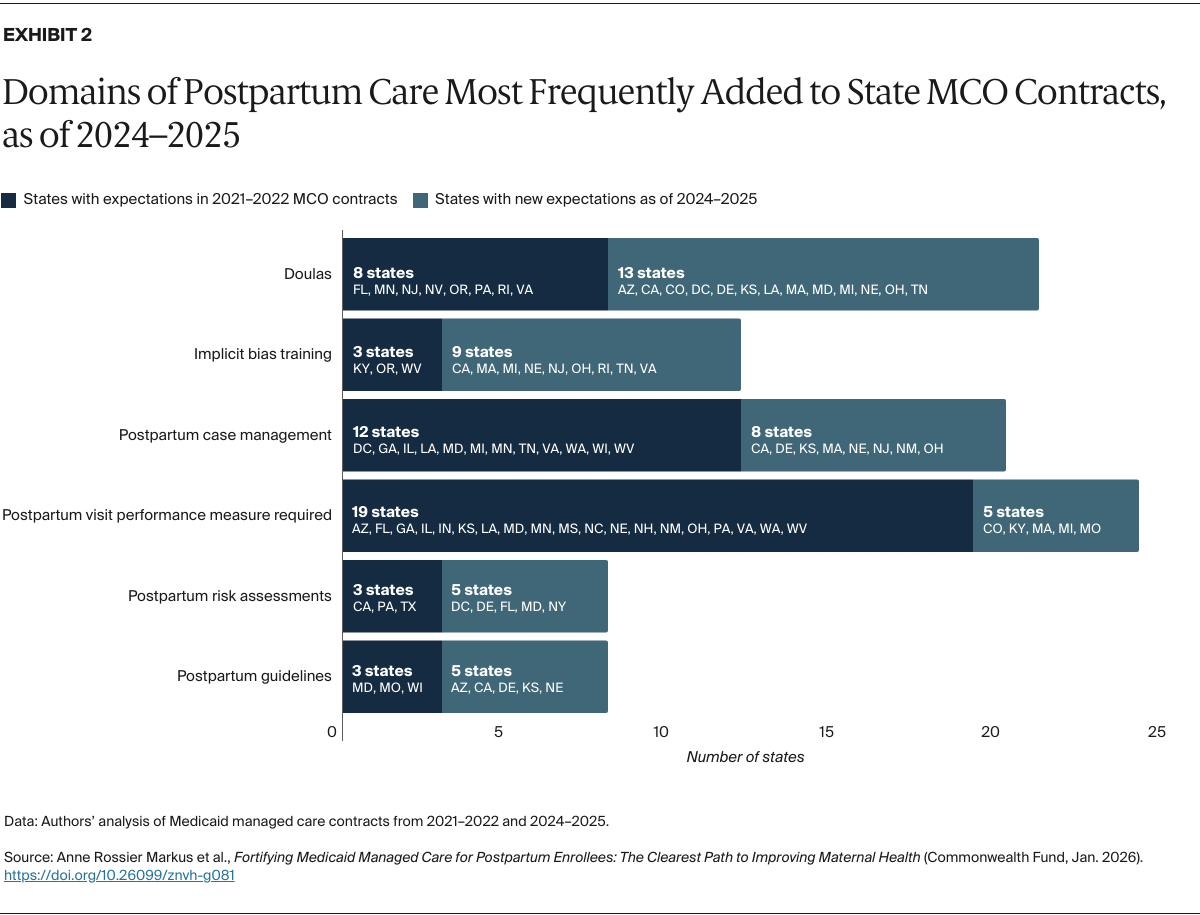

Methods: The study team reviewed MMC agreements from all states to assess whether they addressed any of 30 subdomains of postpartum best practices and clinical guidelines. Contracts from 2021–2022 were compared to those from 2024–2025 to ascertain whether states used the postpartum extension as an opportunity to strengthen postpartum care requirements.

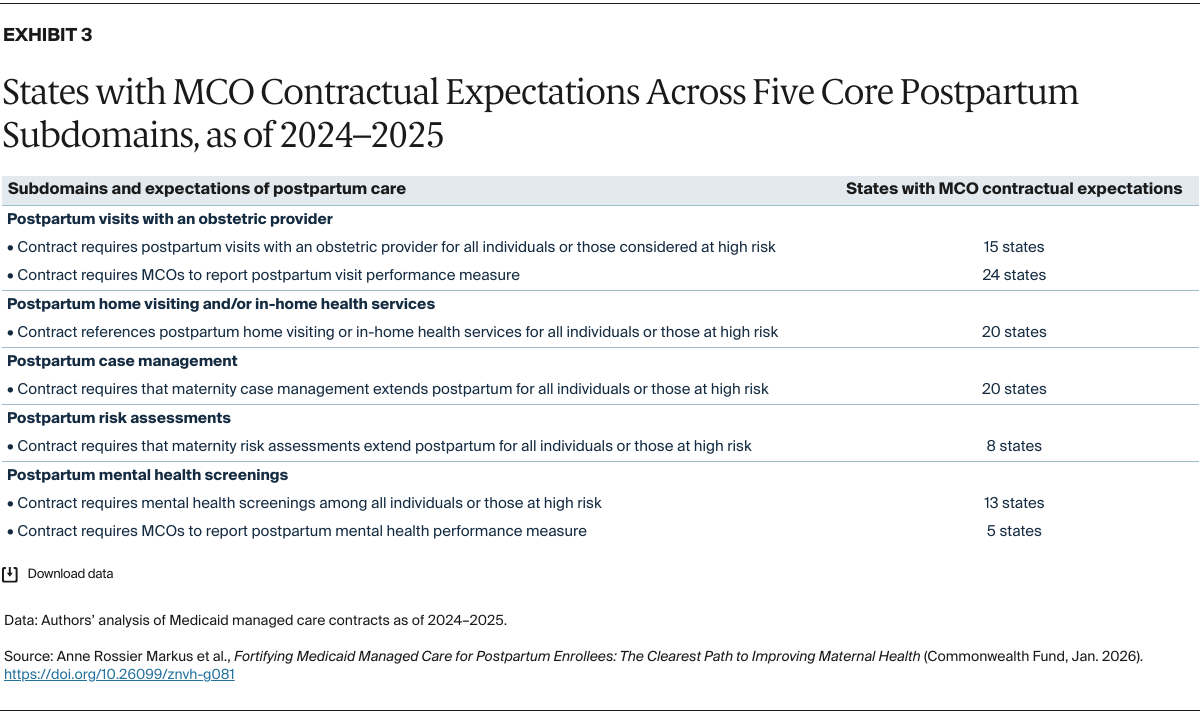

Key Findings and Conclusions: Postpartum contractual language is highly variable across states and often applies to a specific subpopulation only. While MMC agreements tend to fall short of postpartum best practices, states appear to have strengthened their expectations for postpartum care following the postpartum extension. Strengthening the standards to which MCOs are held would likely improve access to and delivery of high-quality postpartum care.

Introduction

As of 2025, 48 states, plus Washington, D.C., provide continuous Medicaid coverage through one year postpartum.1 Without these extensions, up to 48 percent of low-income mothers covered by Medicaid would lose their coverage two months after giving birth.2

Continuous Medicaid coverage in the critical postpartum period increases access to medication and medical care — including preventive services, mental health care, and substance use treatment — and reduces families’ financial burden, such as out-of-pocket spending. It is also associated with better health outcomes, fewer hospitalizations, and fewer emergency department visits.3 Continuous access to postpartum care also has the potential to reduce maternal deaths, as most pregnancy-related deaths occur in the 12 months postpartum.4

On average, nearly half of those who are pregnant and postpartum have Medicaid coverage, and 80 percent of them are enrolled in Medicaid managed care (MMC).5 Within MMC, state Medicaid agencies purchase a package of health care services from health plans known as Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs). In contrast with fee-for-service Medicaid, MCOs are paid a set amount upfront per enrollee. States enter into detailed contractual agreements with MCOs, with the expectation that these health plans will oversee all aspects of care delivery for their designated enrollees. This can include the provision of health services, care coordination, case management, and connection to social services and informal supports, as well as establishing robust provider networks, conducting quality improvement efforts, and overseeing network payment.

The sheer number of postpartum individuals enrolled in MMC underscores the central role that state Medicaid agencies and contracted MCOs play in ensuring access to continuous, high-quality postpartum care. States vary widely in their approach to contracting with MCOs for maternity services, and not all of them integrate recommended, evidence-based practices into contractual expectations.6

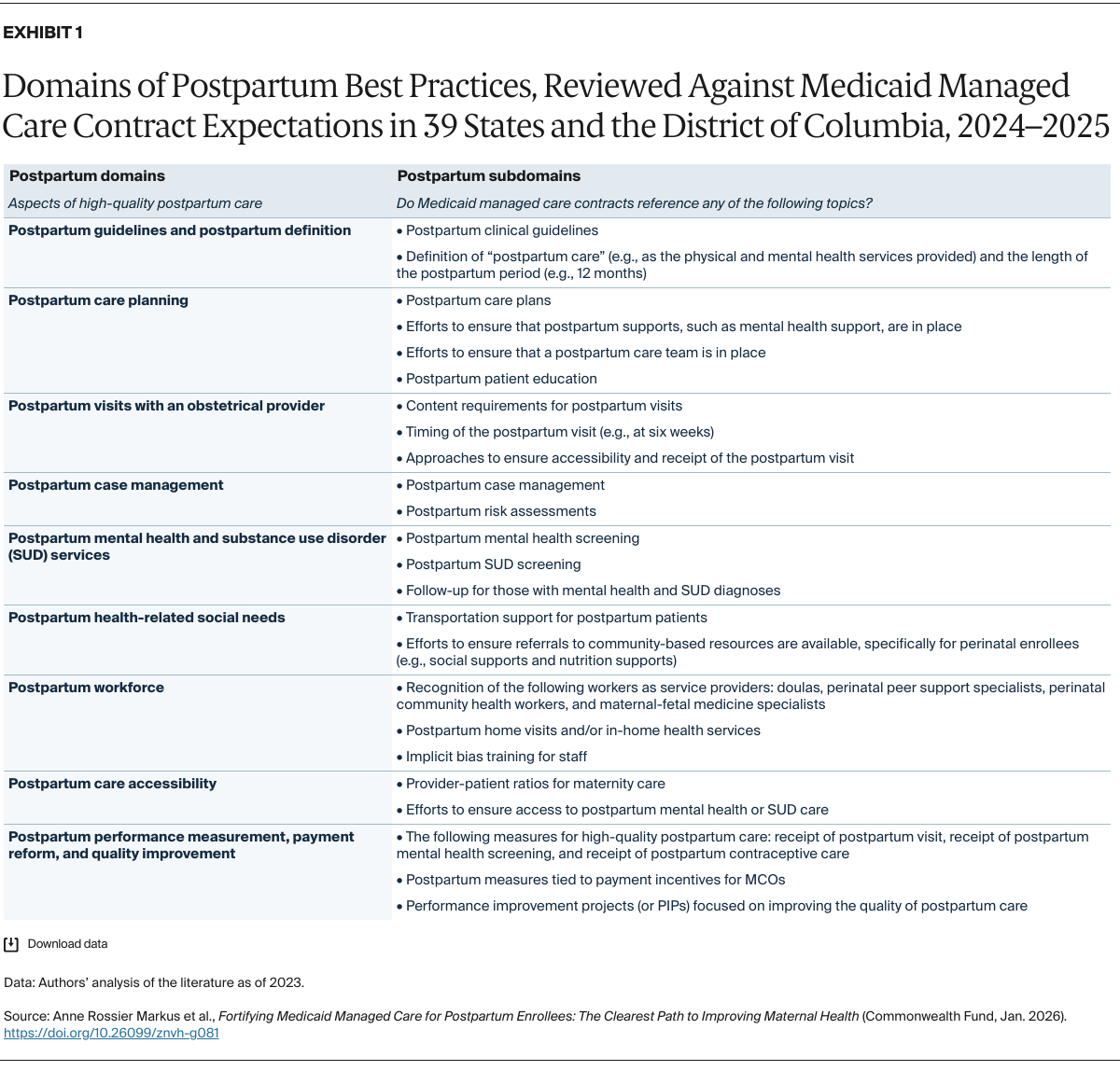

This brief examines state Medicaid postpartum care contractual expectations for MCOs before and after states extended continuous Medicaid coverage to one year postpartum. Thirty-nine states, along with the District of Columbia, used MMC in 2024, and all have extended postpartum coverage to 12 months. For each, we analyzed whether the 2024–2025 “model” MCO contract address nine domains and 30 subdomains of postpartum best practices.7 We then compared states’ 2024–2025 model contracts to those from 2021–2022 to assess whether states used the postpartum extension as an opportunity to strengthen their requirements for evidence-based, clinically recommended, and community-based postpartum services.

What Is High-Quality Postpartum Care?

The nine domains and 30 subdomains of postpartum care are drawn from the latest evidence, clinical guidelines, and best practices for maternity care for people with elevated health and social needs (Exhibit 1).8 They represent the scope of postpartum services, approaches, and standards that should be applied when providing high-quality postpartum care to low-income individuals, with the goal of improving health care access and reducing postpartum disparities.