Policymakers are increasingly interested in reforming how commercial insurers use prior authorization (i.e., requirements that clinicians seek approval from insurers before providing treatment). Some states have enacted or proposed legislation limiting the use of prior authorization across broad categories of services, such as mental health care and cancer treatment. At the federal level, legislators have introduced measures to regulate prior authorization processes in Medicare Advantage plans. And recently, a group of large health insurers announced a commitment to streamline and simplify prior authorization and to reduce its use across a range of medical services.

Prior authorization is widely disliked by patients and clinicians, many of whom believe it delays care and has a negative effect on clinical outcomes. But managed care tools, like prior authorization, can help encourage the efficient use of health care resources. This is particularly important in the United States, which has persistently high health care spending, some of which is spent on low-value or wasteful care. Prior authorization has some advantages over other managed care tools. Unlike claims denials, prior authorization occurs before a service is rendered, thereby helping avoid nonpayment when it is too late to change a treatment plan. And unlike patient cost sharing, prior authorization is targeted to specific services and clinical coverage rules. Perhaps for these reasons, traditional Medicare recently announced a new demonstration model to incorporate more prior authorization into Medicare Part B.

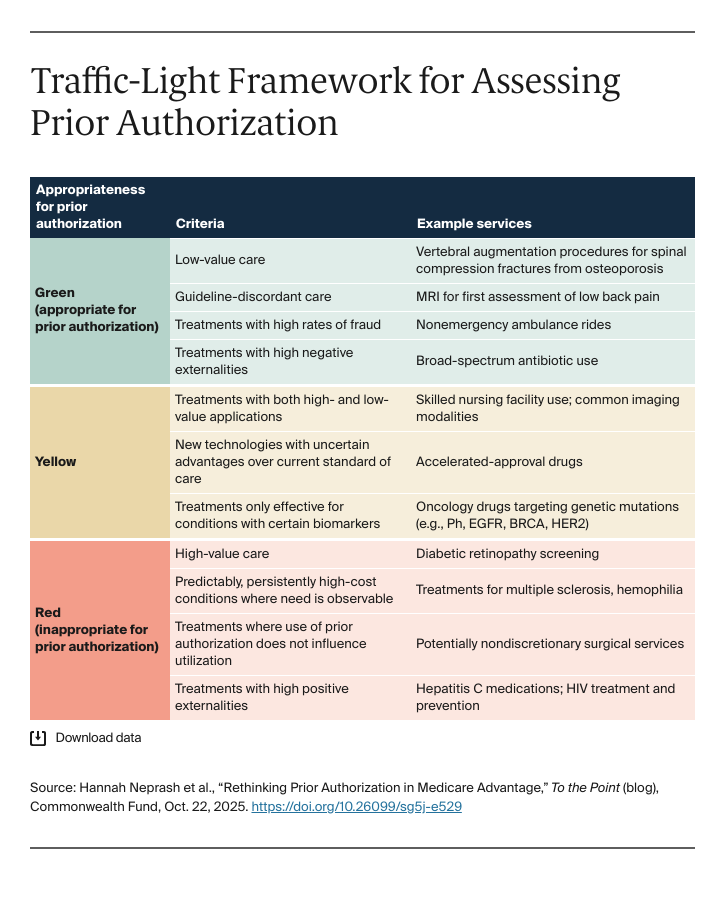

But there should be thoughtful limits on how prior authorization is required. For legislators, regulators, and plans considering ways to reduce its use, the guiding principle should be whether services align with clinical evidence, rather than whether doctors and patients are willing to overcome burdensome administrative hurdles. With this in mind, we propose a traffic-light framework that is informed by insights from clinical practice and health economics.