Introduction

Why a State Medicare Scorecard?

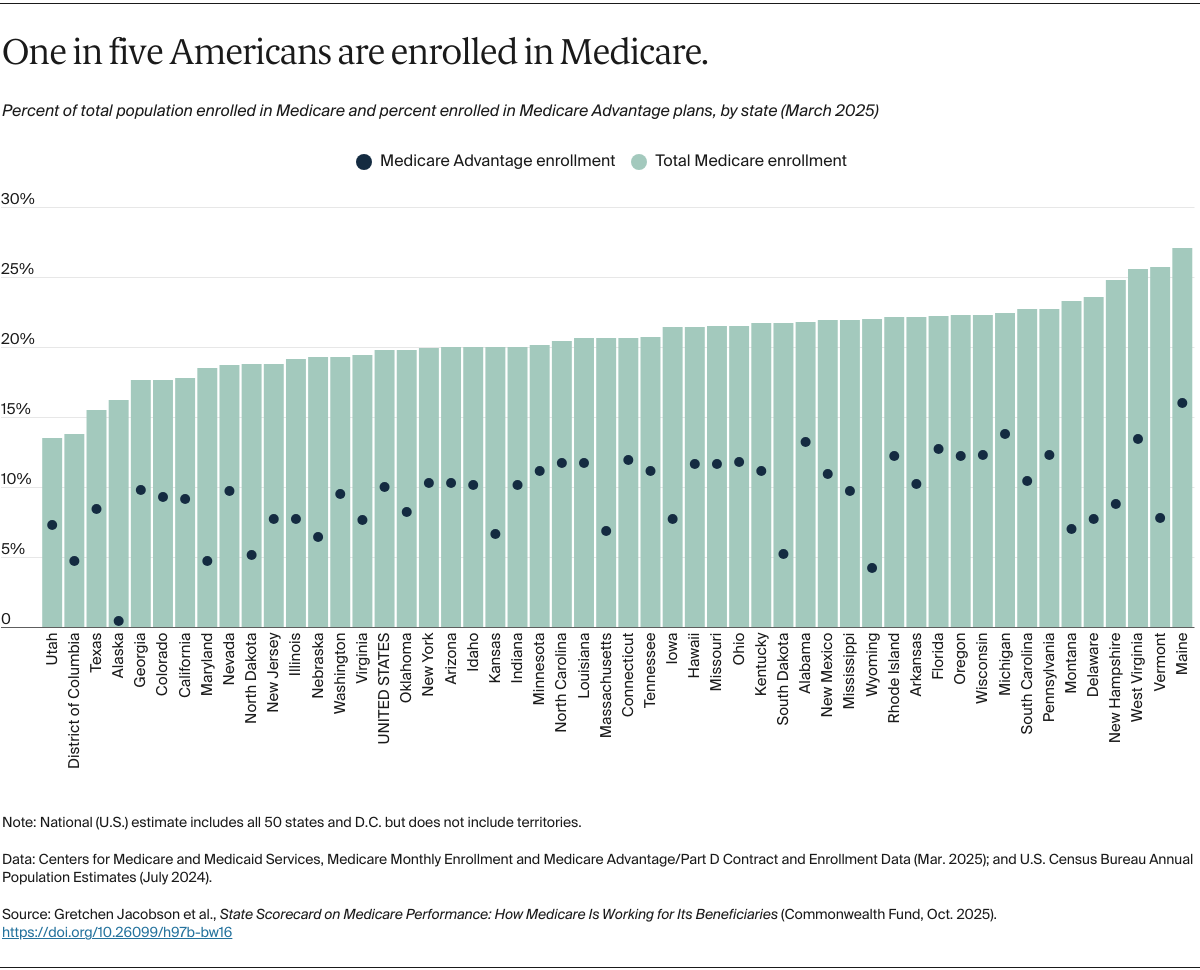

Medicare, established 60 years ago, provides health care coverage for more than 68 million Americans, including nearly all adults age 65 and older as well as 7 million younger people with disabilities.1 Over the decades, the federally administered program has been a pioneer of change in U.S. health care, often serving as a testing ground for reforms in how health care is delivered and paid for. Advocates for national health insurance, meanwhile, often point to Medicare as a potential model.

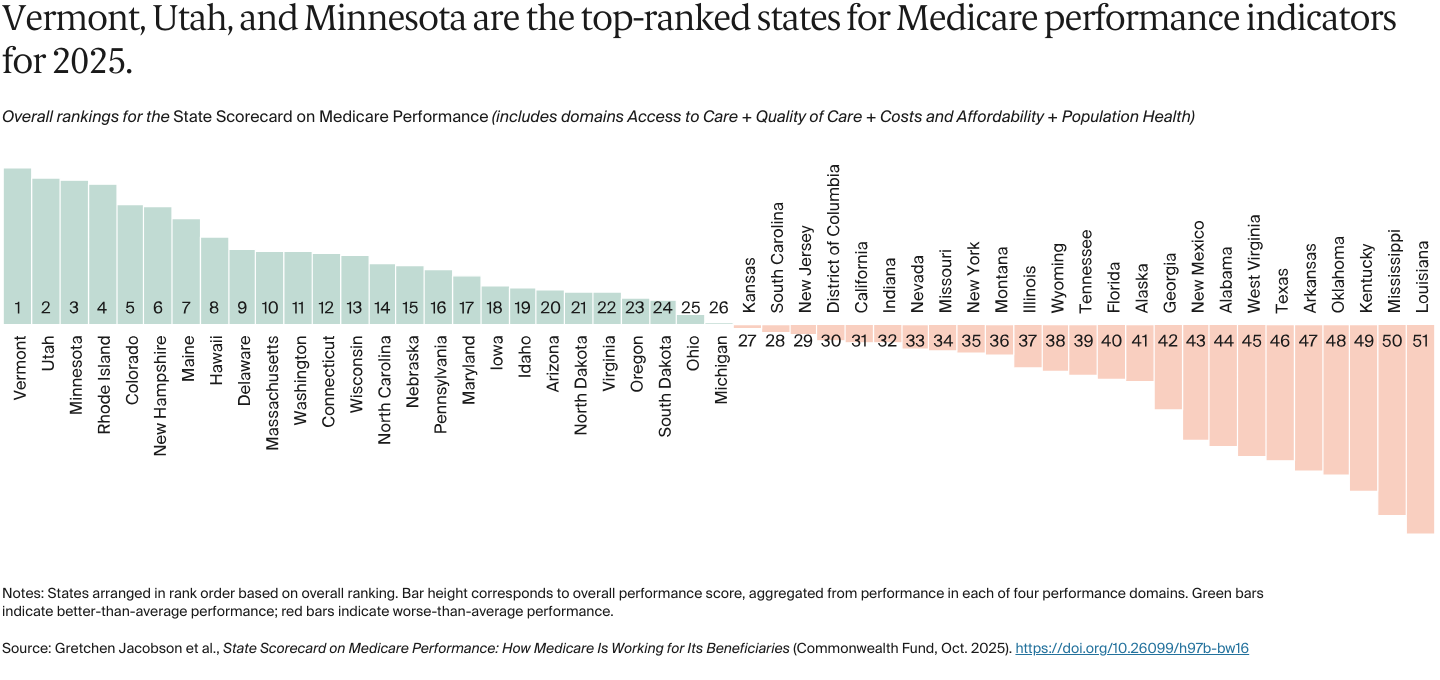

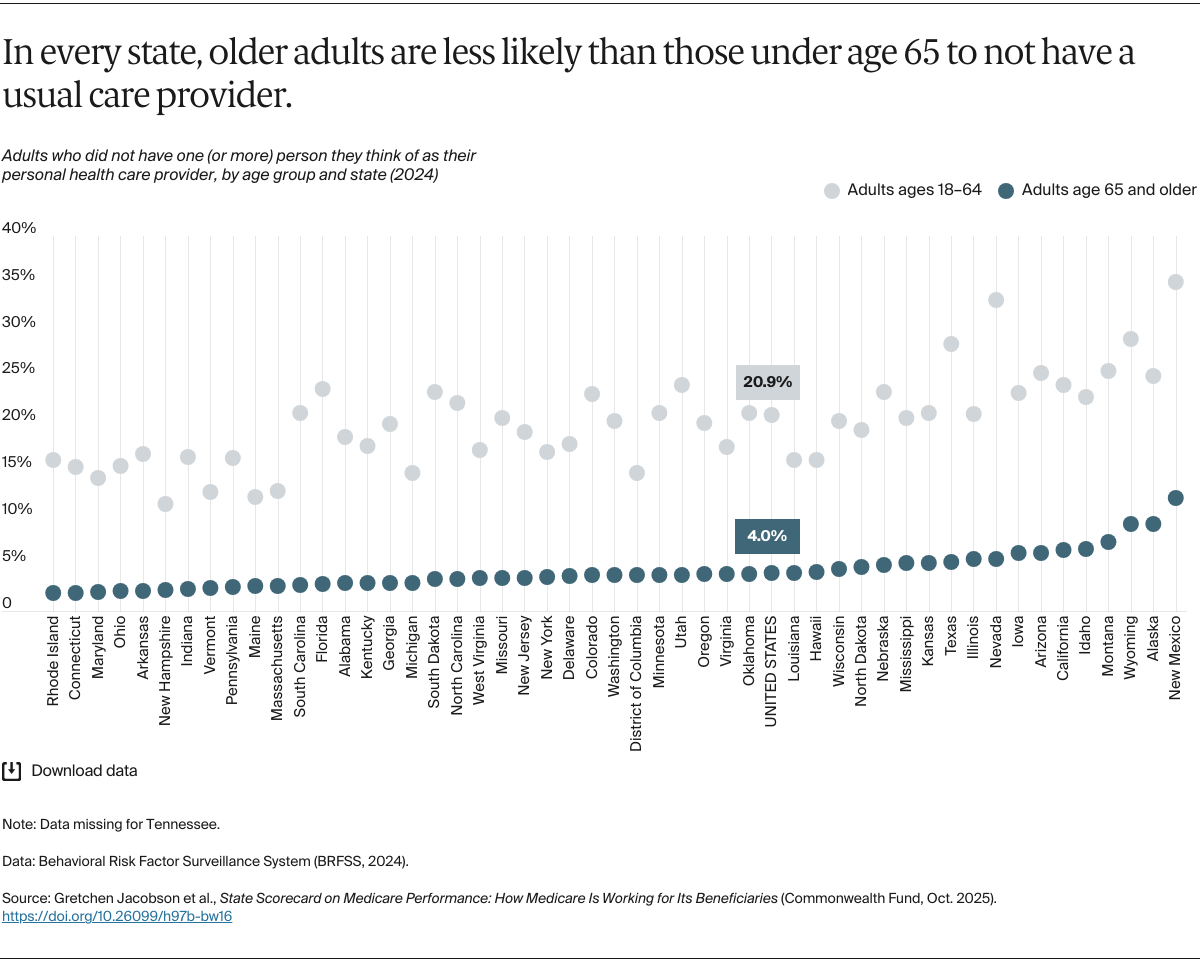

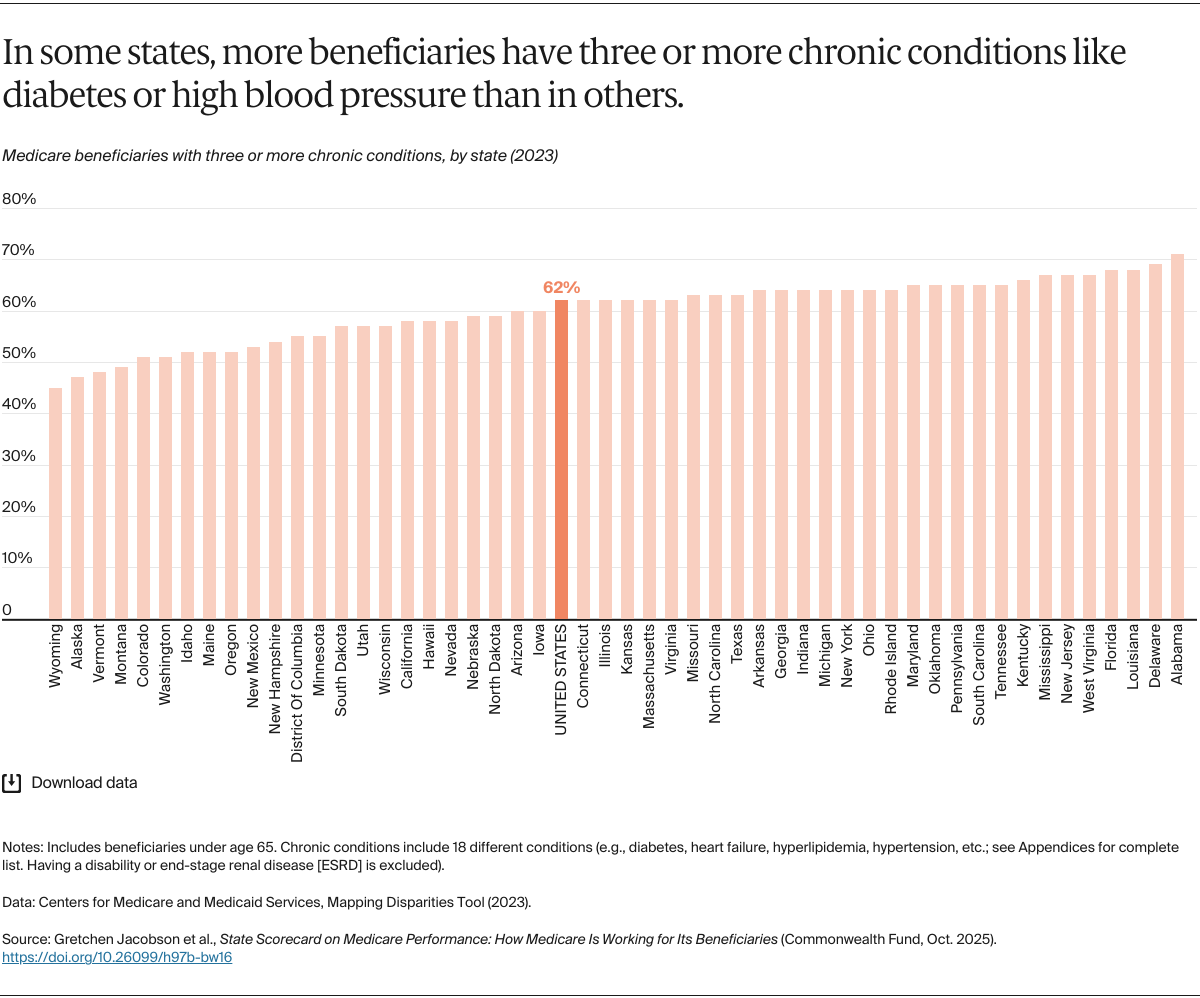

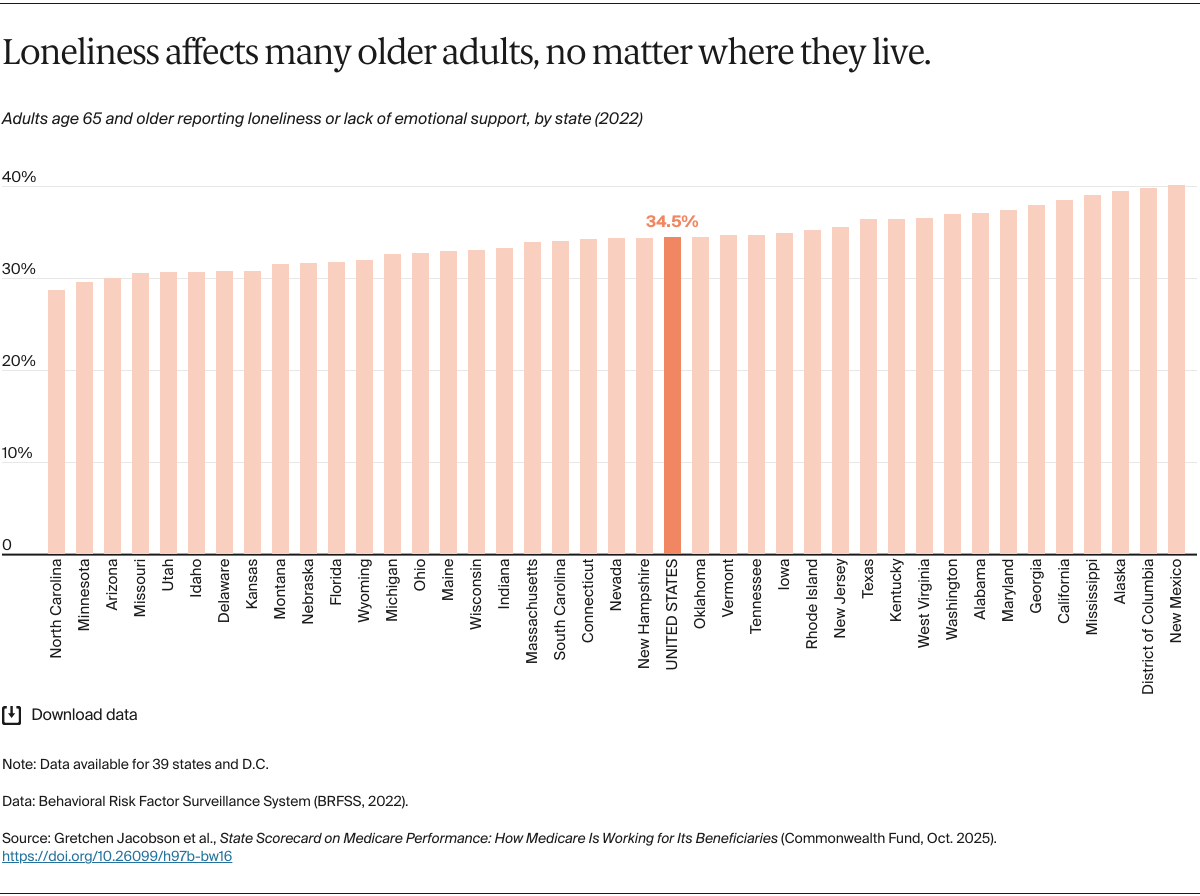

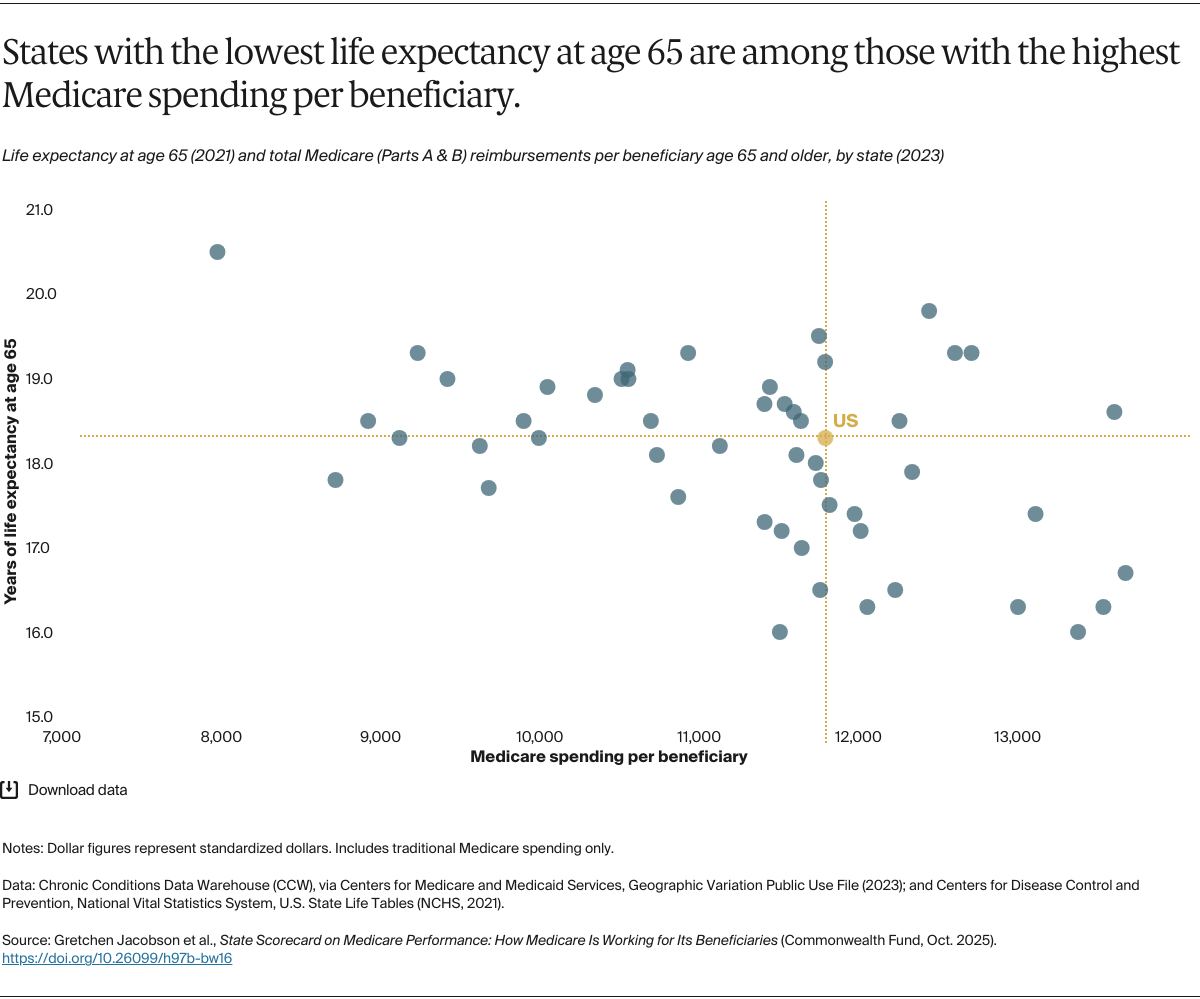

The importance of Medicare to the nation’s health and health care system is why it’s critical that we understand how well the program is serving the people it covers. While originally designed to provide uniform benefits across the country and to enable access to high-quality, affordable care, where beneficiaries live makes a difference in how they experience Medicare. There are several reasons for that variation:

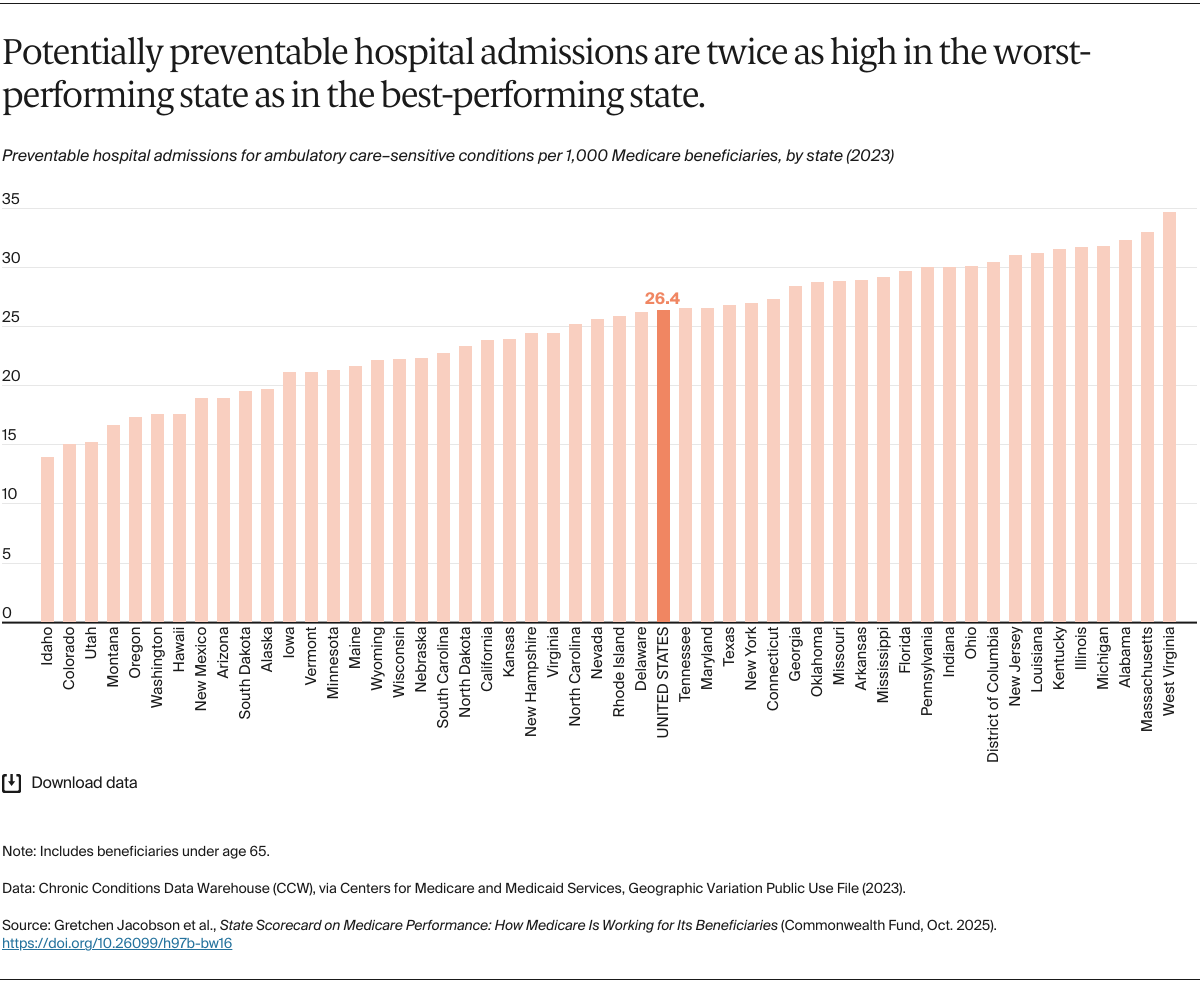

- Each state’s health care infrastructure is unique, making access to doctors and hospitals easier in some places than others. Practice norms of local health systems and providers differ as well, meaning there is variation in which tests or treatments are commonly provided for a given condition. Beneficiaries’ access to nonmedical supports, like care coordination services and transportation assistance, which can play a key role in health, also differ.

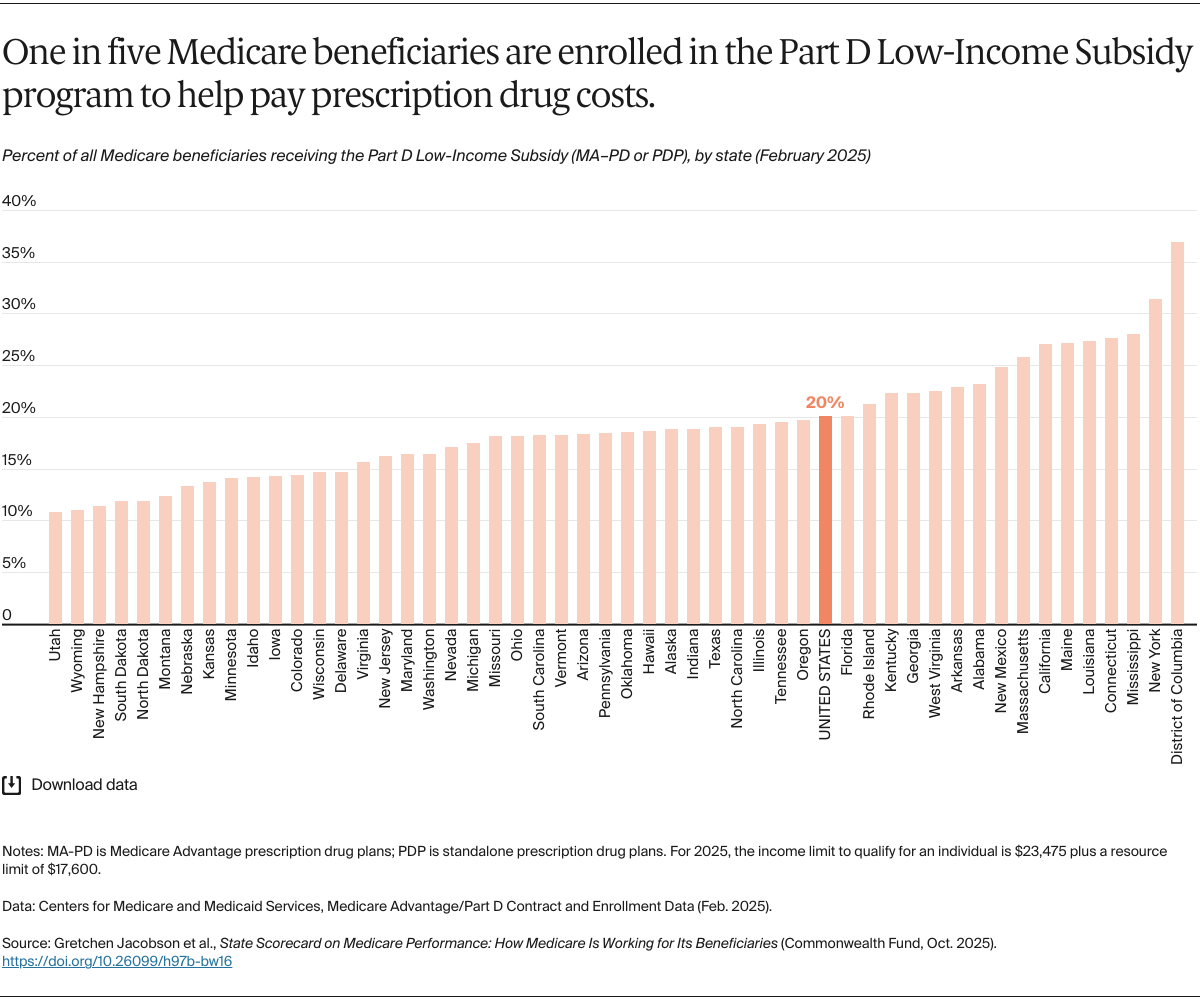

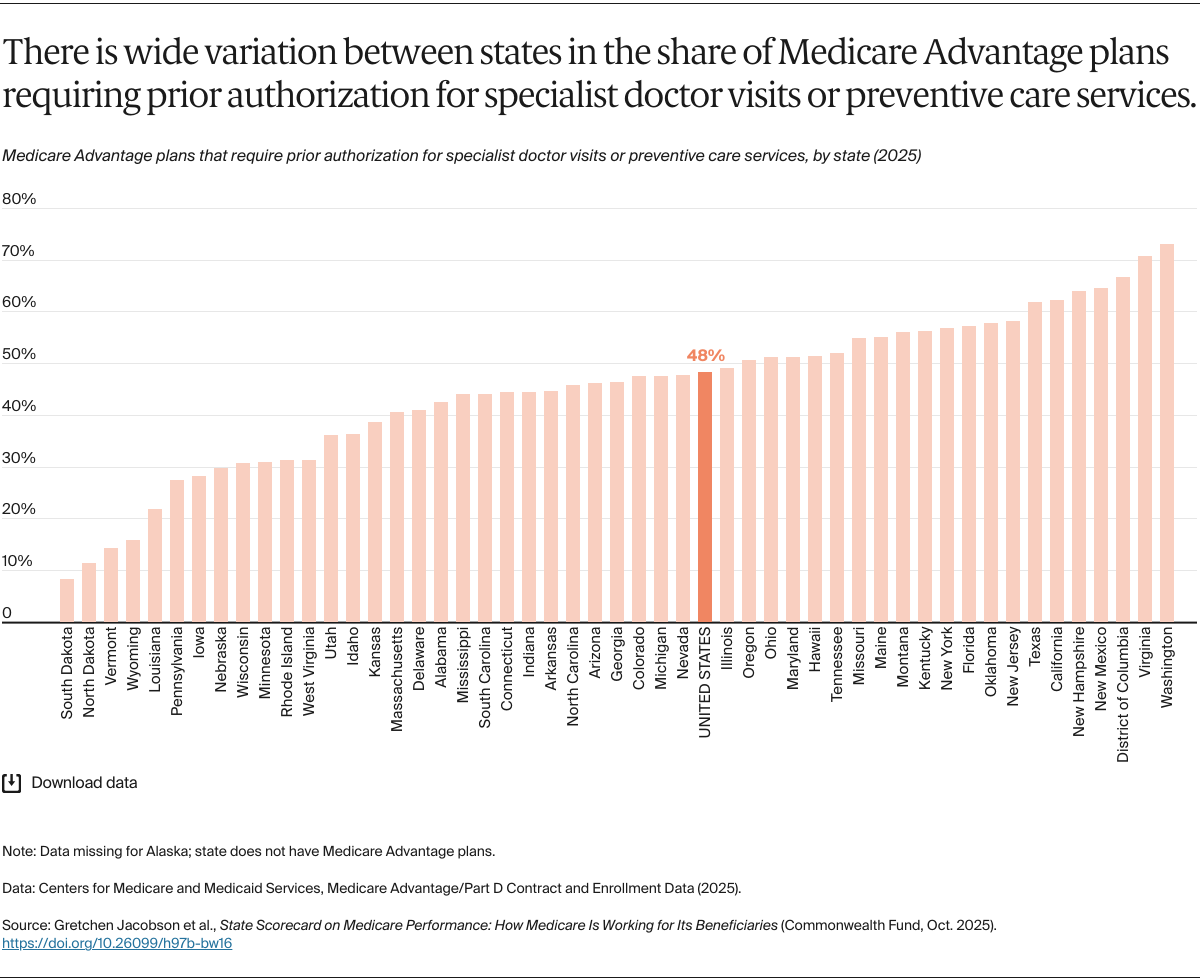

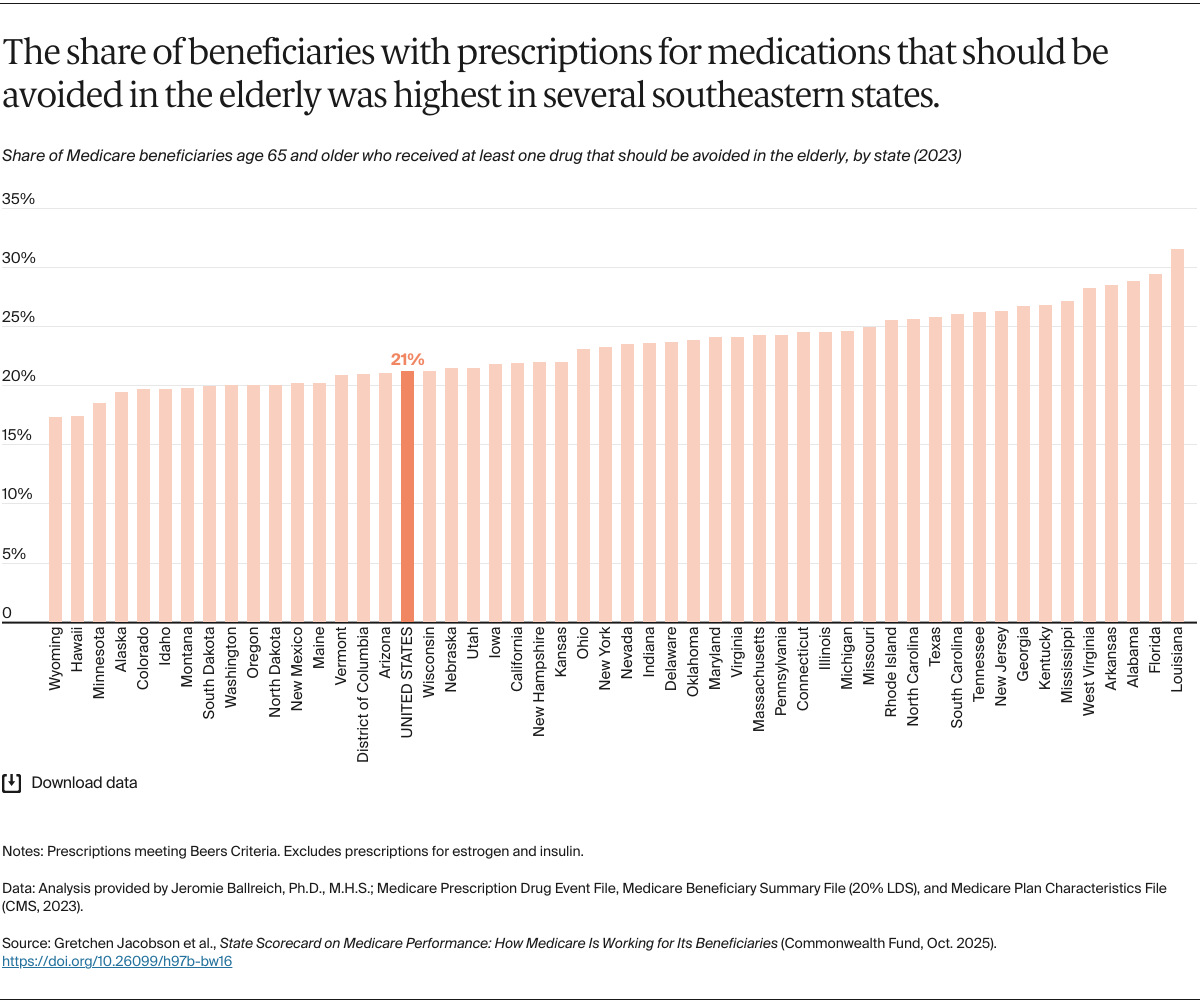

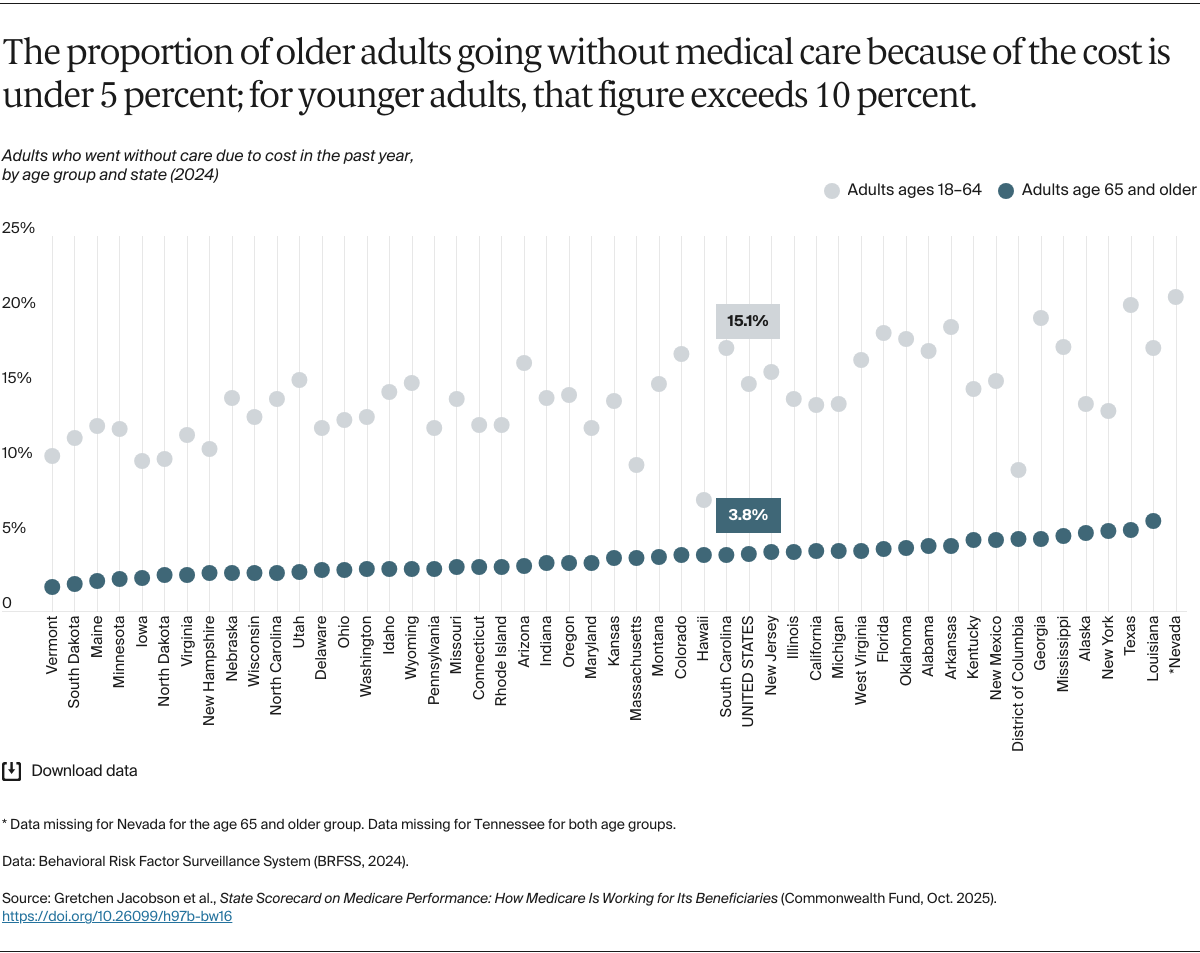

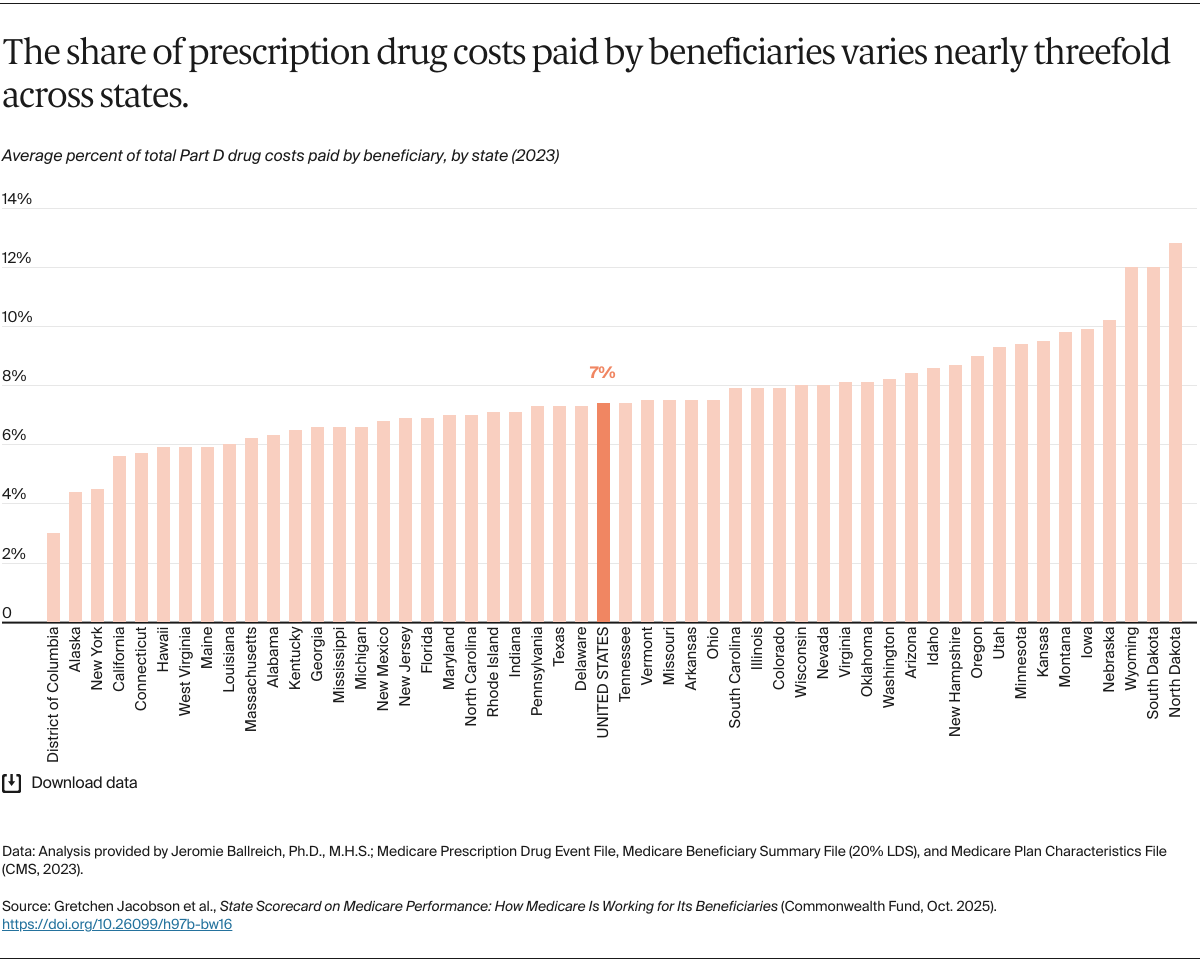

- Most Medicare beneficiaries receive either some or all their Medicare benefits through private insurance plans, including Medicare Advantage plans and prescription drug plans. The availability of these plans differs across counties and states, as does their generosity of coverage, their premiums and cost sharing, and the access they offer to physicians, hospitals, and pharmacies. Most beneficiaries have some supplemental coverage to help with deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments or to fill gaps in Medicare’s benefits. Differences in types of Medicare coverage and supplemental coverage can result in variations in out-of-pocket costs and care.2

- Beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs, particularly for most outpatient services, are often a percentage of what Medicare pays for those services. Medicare payments to health care providers can differ based on geographic area and local health care costs. As a result, beneficiaries from region to region can pay different amounts for the same service.3