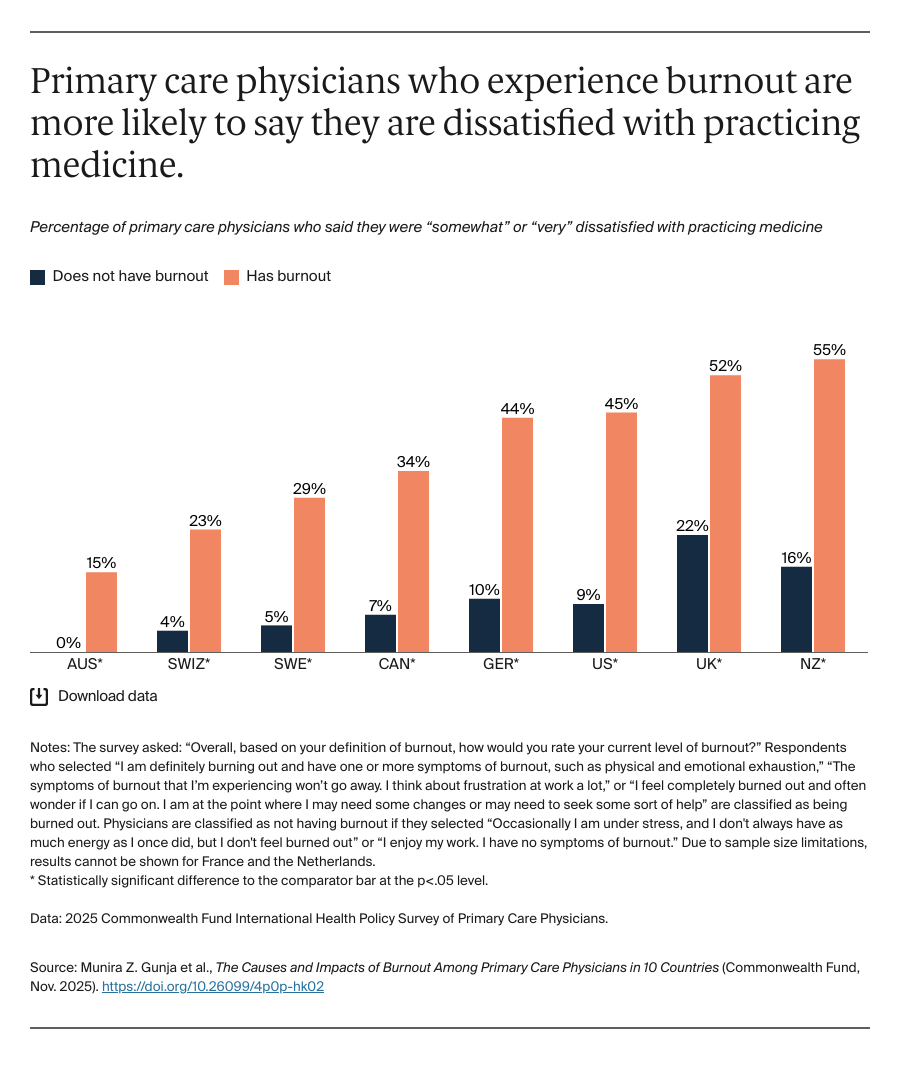

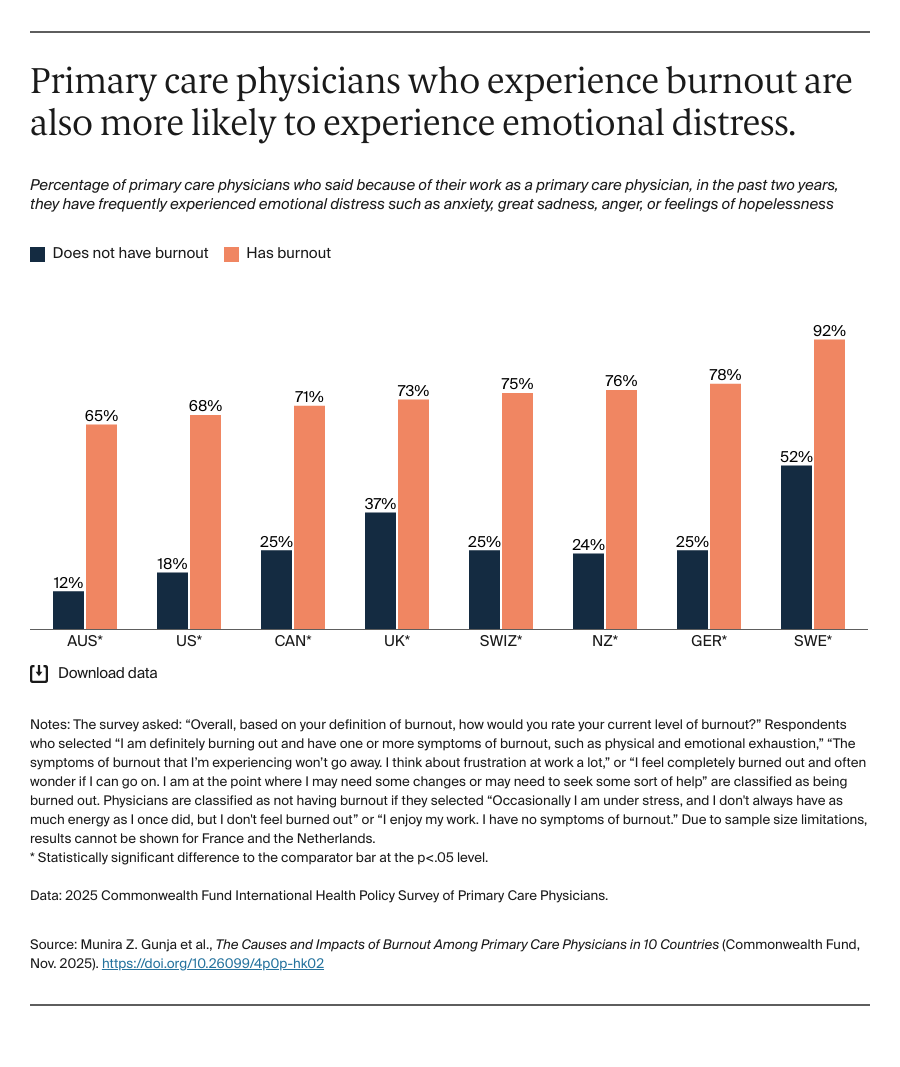

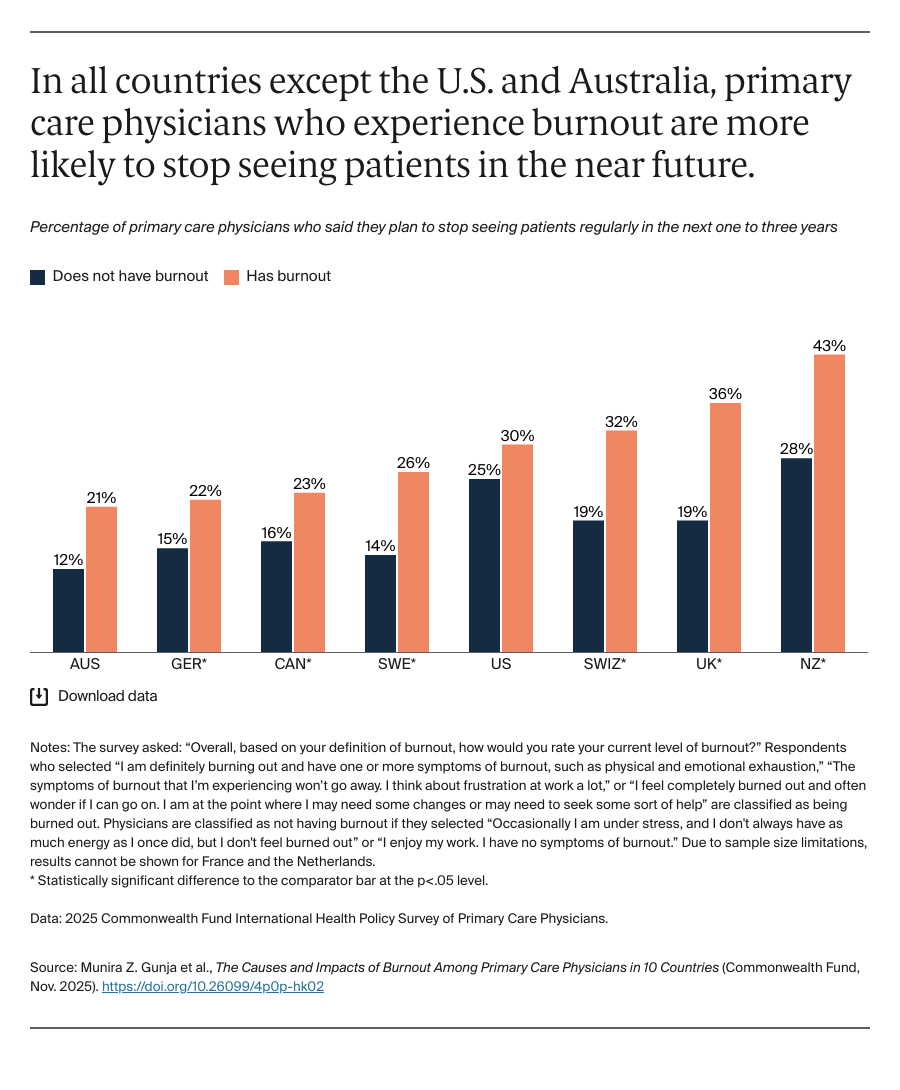

Across nearly all countries, those physicians who experience burnout are more likely to be dissatisfied with practicing medicine and to experience emotional distress than physicians who are not experiencing burnout. They are also more likely to say they plan to stop seeing patients in the near future.

Conclusion

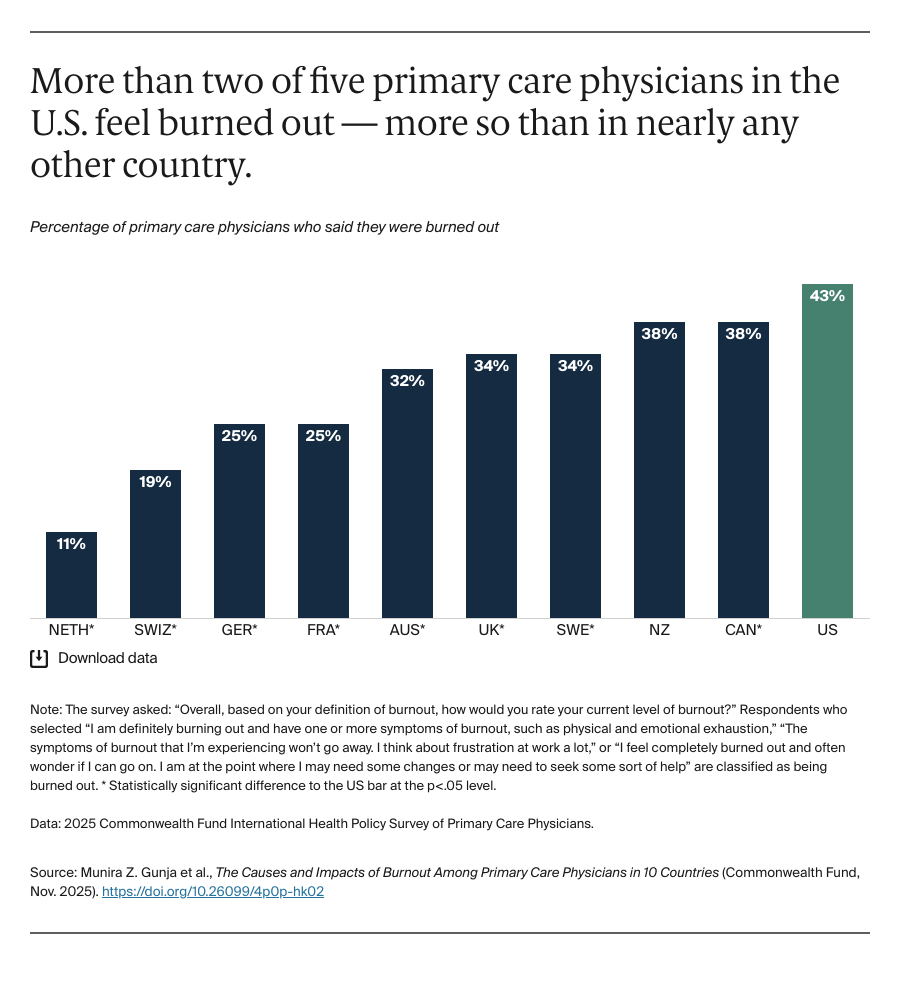

Though primary care is critical to a high-performing health care system, the Commonwealth Fund survey shows that in the major health systems studied, many primary care physicians are burned out. These physicians are more likely to experience emotional distress and more likely to say they intend to leave the field in the near future. Administrative burden, workload, and moral distress all contribute to heightened feelings of exhaustion and burnout. Additionally, repeated moral distress, heightened by the COVID-19 pandemic, can lead to demoralization, a close cousin to physician burnout. Physicians who feel overwhelmed by bureaucracy and persistent inequities may also choose to leave the profession.

Several countries surveyed have taken steps to support clinicians by streamlining administrative tasks and implementing initiatives to bolster the well-being of the workforce. Payers, policymakers, and health care leaders in the United States can learn from these programs and develop context-specific interventions.

Strategies to Tackle Burnout

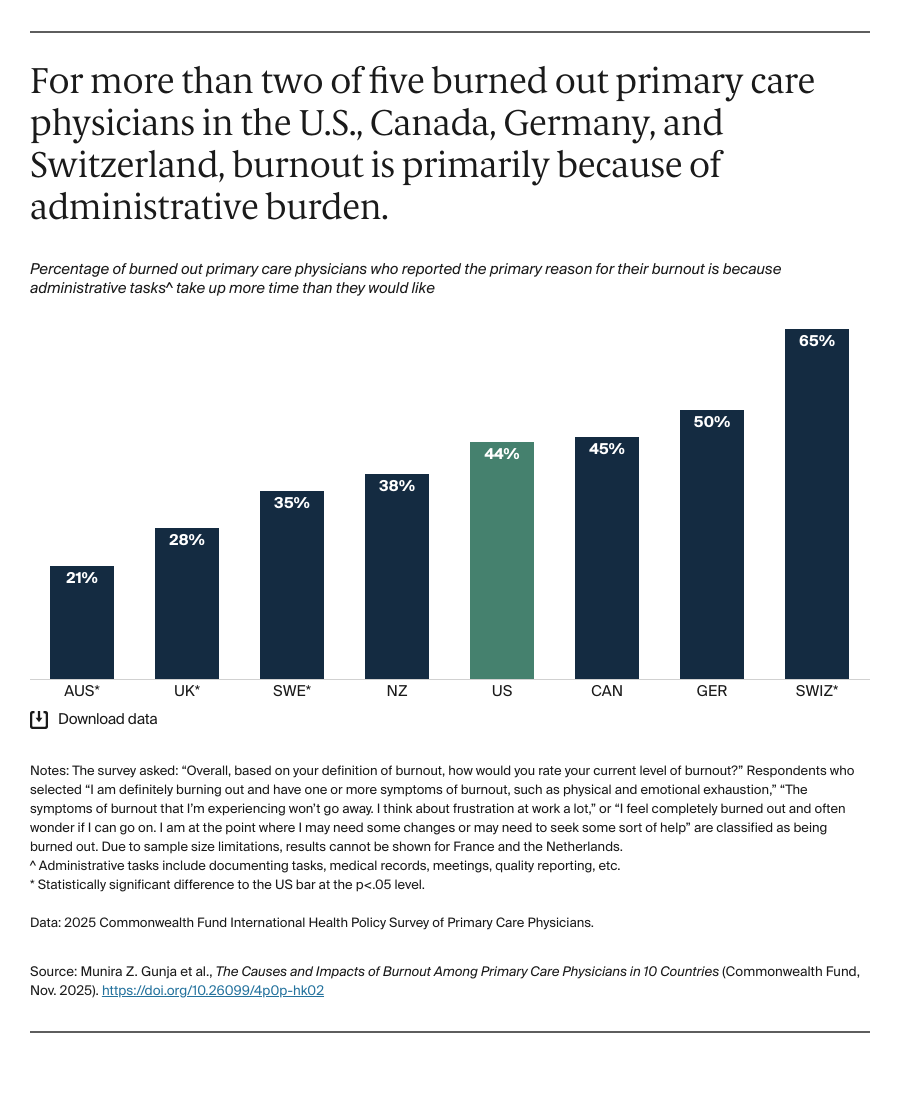

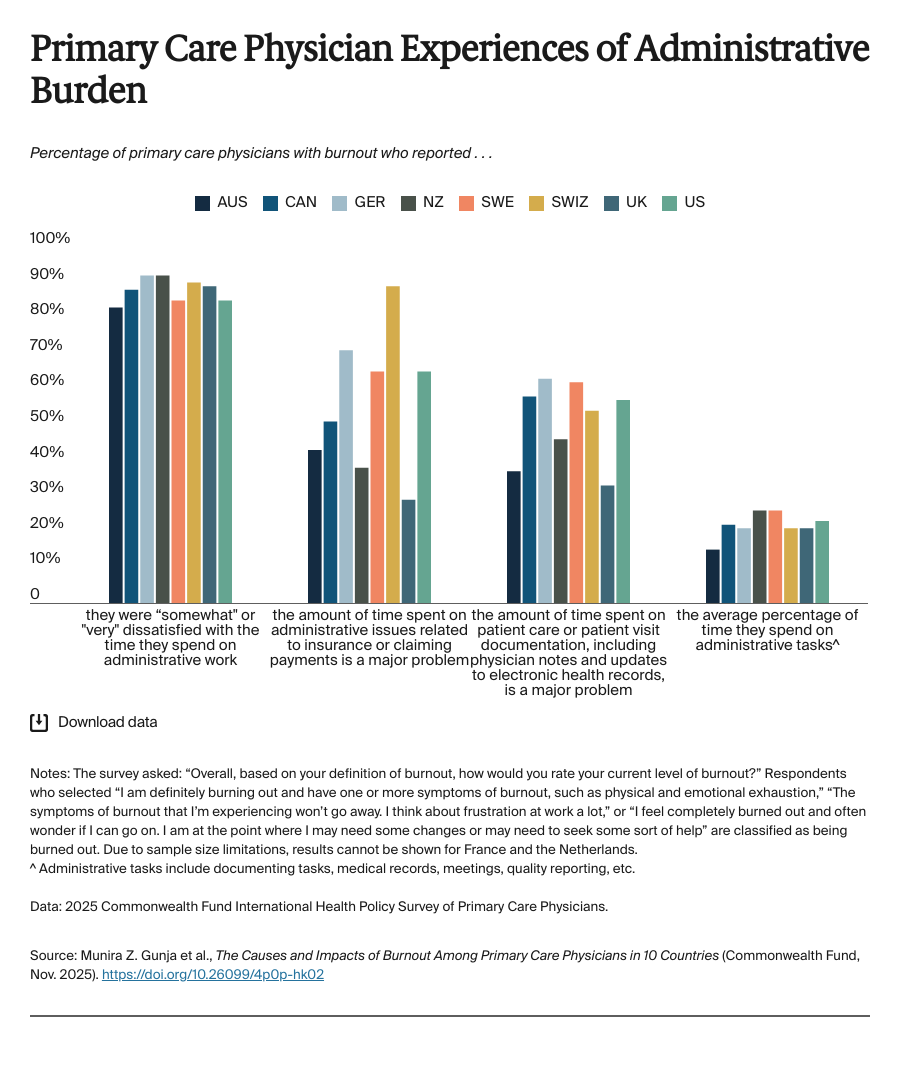

Administrative burden. Australia reported some of the lowest rates of burnout due to administrative burden — half the rate in the U.S. Through the Provider Connect Australia System, the country has reduced the burden of administrative tasks like billing and communication for clinicians and practices. Unlike the U.S., which has a fragmented reporting system that is often unique to each payer and practice, Australia has a centralized platform for billing, documentation, and messaging, allowing seamless communication across providers, practices, and businesses. Australia’s government has also passed legislation to enable simplified, electronic billing.

While the U.S. does not have a single system for documentation, billing, or communication, there are opportunities to reduce administrative burden for clinicians. In 2022, the U.S. Surgeon General recommended streamlining reporting requirements across payers — both public and private — to reduce duplicative documentation. This would ensure quality measurement is meaningful and not overly burdensome. Leveraging technology, like machine learning, automated clinical processes, and more, also could reduce physicians’ administrative burden. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently announced a new model to streamline administrative tasks through enhanced technology, for example. Congress could also establish a clearinghouse and standardized platform for billing submissions, which could improve claims and payment processes while reducing costs associated with operating separate systems across providers and payers.

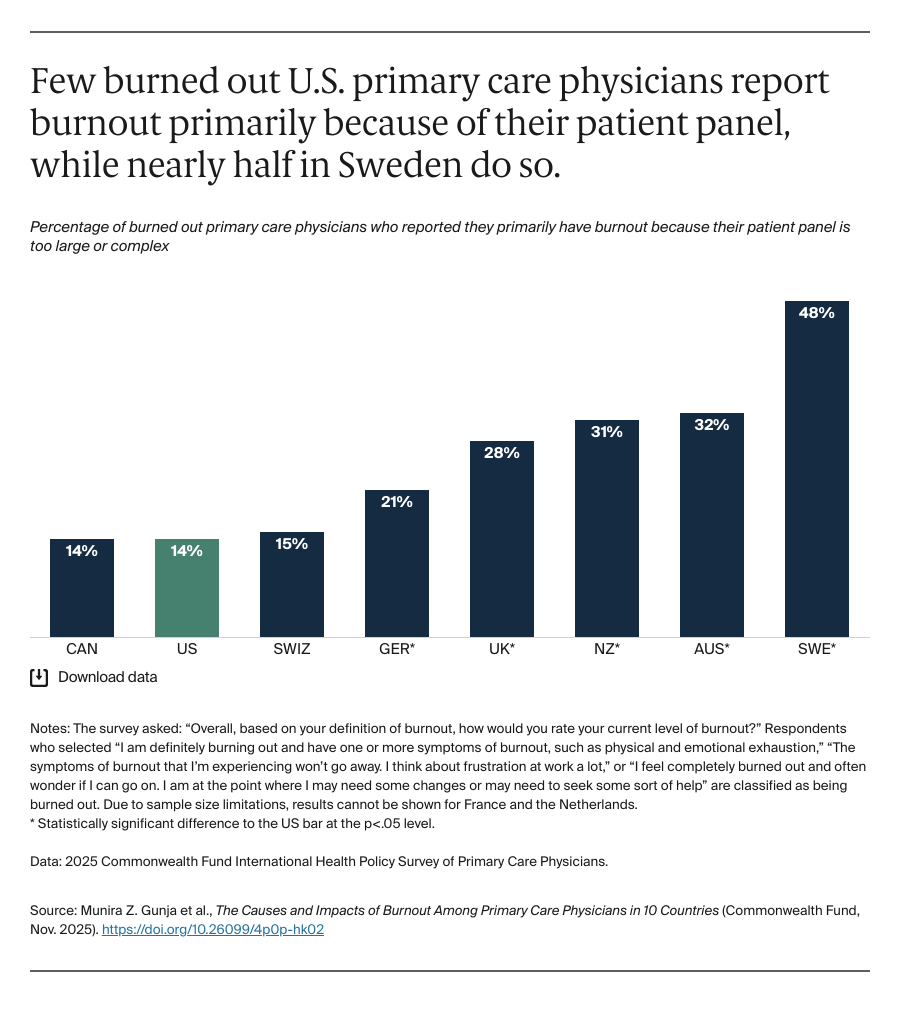

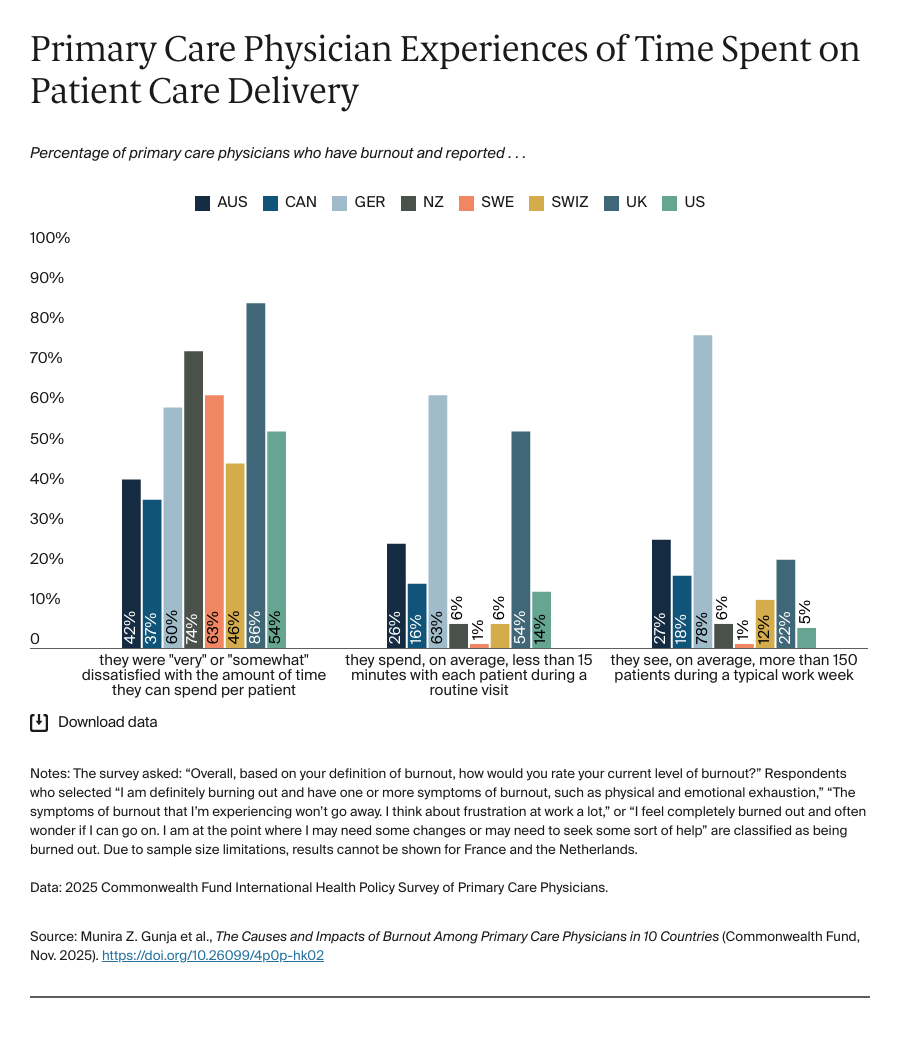

Time spent with patients. Although nearly half of PCPs in Sweden with burnout reported their burnout was because of their patient panel, physicians there are the least likely to have large patient panels and, on average, spend the longest time with each patient for routine visits. Sweden is one of the few countries to adopt capitation for primary care — providing a fixed payment for each patient — which does not incentivize a large number of patient visits. However, adults in Sweden are also among the least likely to report having a regular doctor. Our findings suggest that longer consultations may be contributing to burnout if physicians cannot accommodate all patients in need of care.

Most U.S. PCPs said they were dissatisfied with the time they could spend with each patient, aligning with other research finding that physicians need an estimated 27 hours each day to complete all the tasks expected of them and follow all recommended care actions. In addition to the strategies for addressing administrative burden, the U.S. health system could right-size the panels of physicians, bringing the number of patients in line with the time available for both clinical care and administrative tasks. Value-based payment, when appropriately executed, can reduce the volume of patients seen per day and increase the time spent with patients. Growing the workforce and leveraging team-based care — where different types of clinicians come together to deliver care through delegation and communication — can take the burden off current physicians to see more patients than they have capacity for. One example is a health system in Virginia that has sought to strengthen its clinical culture by ensuring clinicians, like nurse practitioners, can practice to the top of their licenses. This can help clinical teams effectively delegate tasks across clinicians. Additionally, the health system is protecting time for clinicians to work on administrative tasks and implementing workplace well-being trainings.

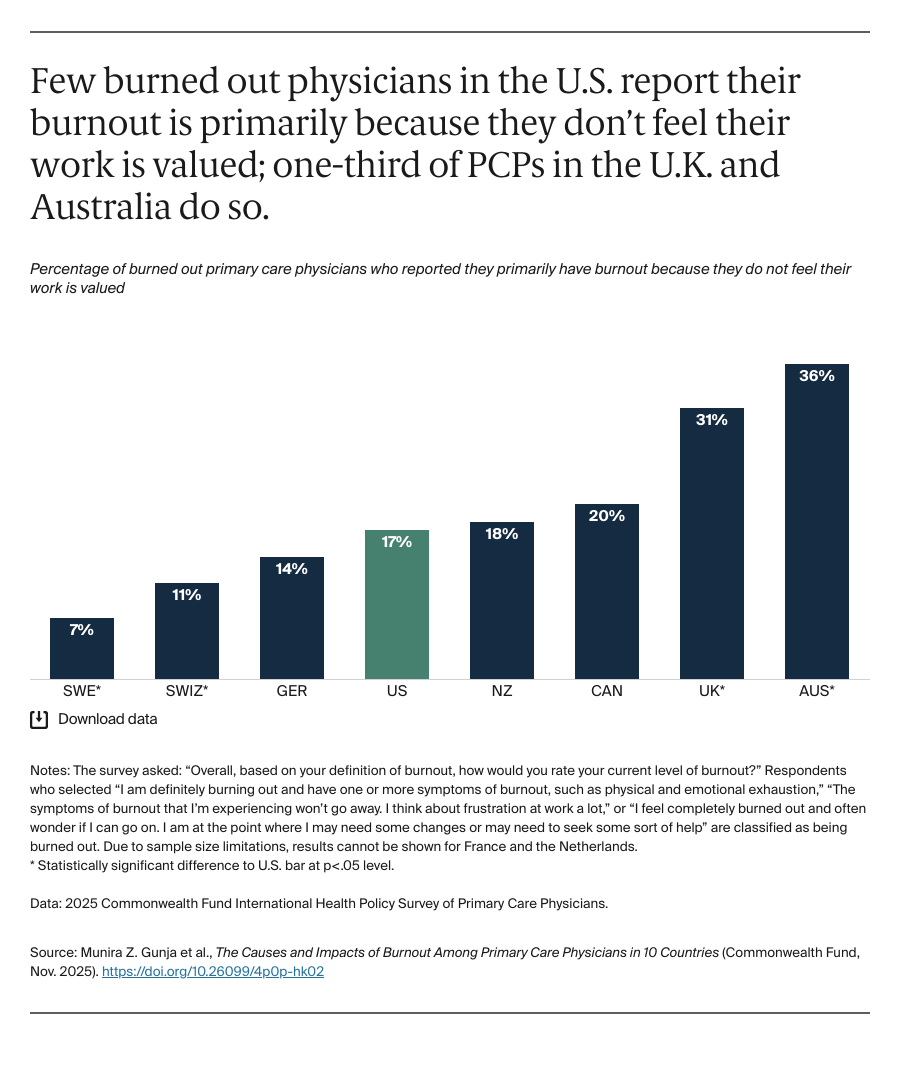

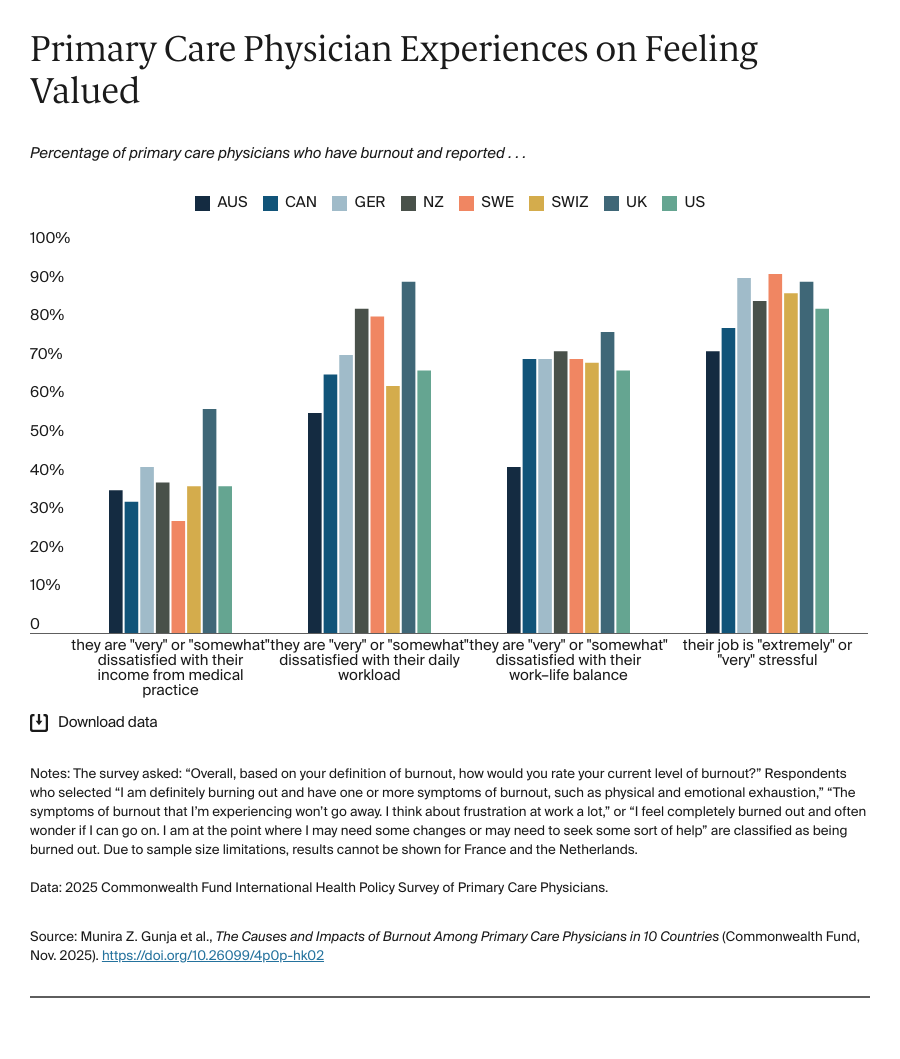

Feeling valued. In our study, primary care physicians experiencing burnout in Switzerland were among the least likely to report feeling burned out because they did not feel valued. More than three of four PCPs in the country also reported satisfaction with practicing medicine overall (data not shown). The Swiss government has made significant investments in recent years to strengthen primary care, including increasing the number of physicians trained in the country and strengthening primary care education at both the undergraduate and graduate levels to attract more physicians to the field. The proportion of doctors practicing in group practices over solo practices, and working fewer than 45 hours a week, has also risen since 2012 — all factors which may be contributing to higher satisfaction.

In the United Kingdom, burned out primary care physicians were more likely to report they are dissatisfied with their daily workload, work–life balance, and income from their medical practice, compared to physicians in other countries. Through its NHS Long Term Workforce Plan, the NHS England is striving to create a compassionate, inclusive, and values-driven culture through managerial support for staff professional development, supporting the health and well-being of staff, and allowing for more flexible work options.

Around the world, professional associations, medical schools, health care organizations, and other stakeholders can all play a role in restoring joy to medicine. Increasingly, profit- and productivity-driven health systems are diminishing the value clinicians feel in their work while increasing their stress and burnout. Through stronger clinical leadership and ethical frameworks, and by regrounding medicine in the moral obligations of clinicians, we can restore physicians’ sense of pride and value in their work.

The primary care workforce in all health systems in this analysis — despite being structured differently — are struggling with burnout. The reasons, however, vary. Addressing the administrative burden PCPs face while supporting their mental and physical well-being are necessary steps for retaining and recruiting physicians to the field and ensuring patients can access high-quality care.