Introduction

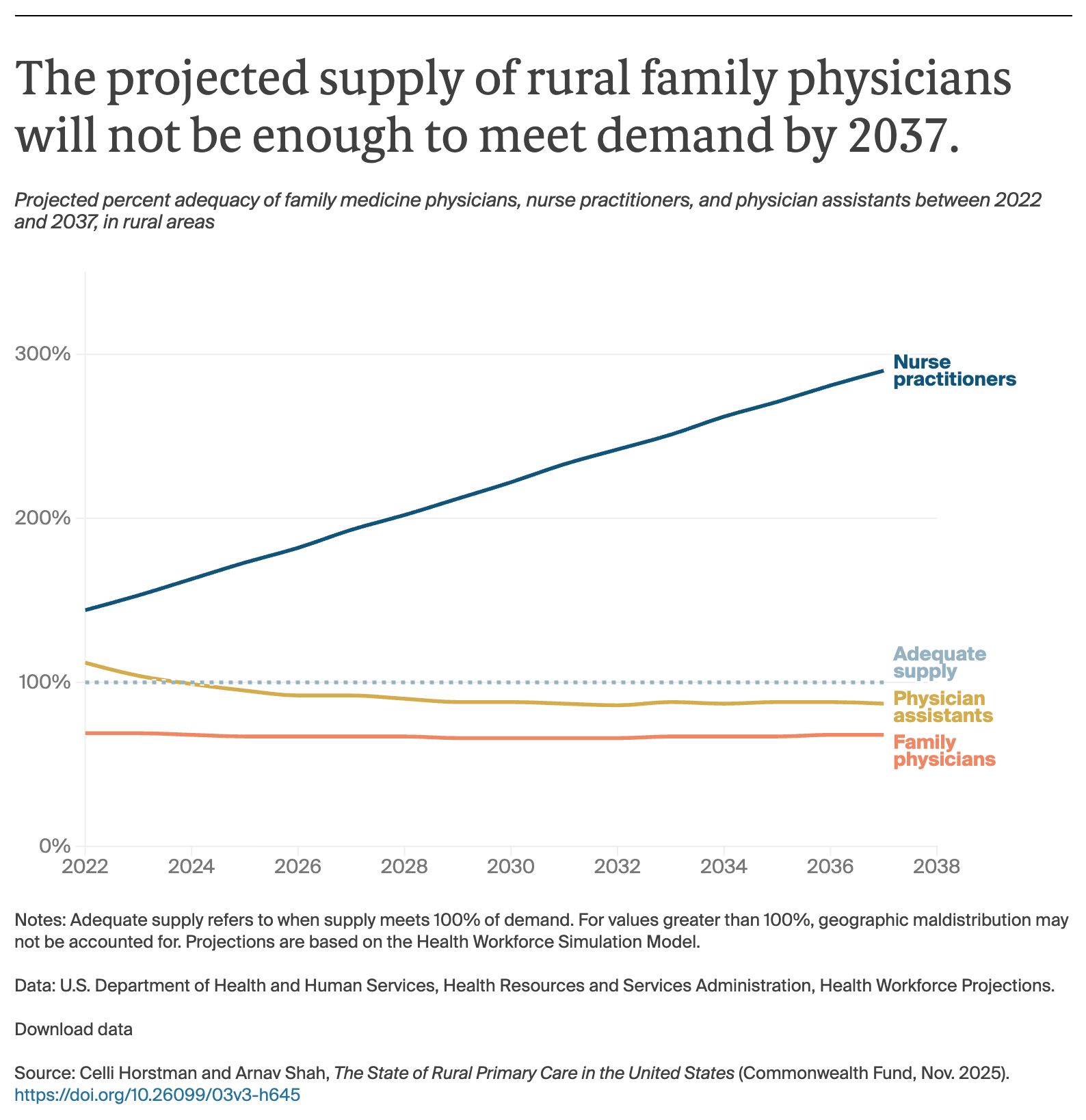

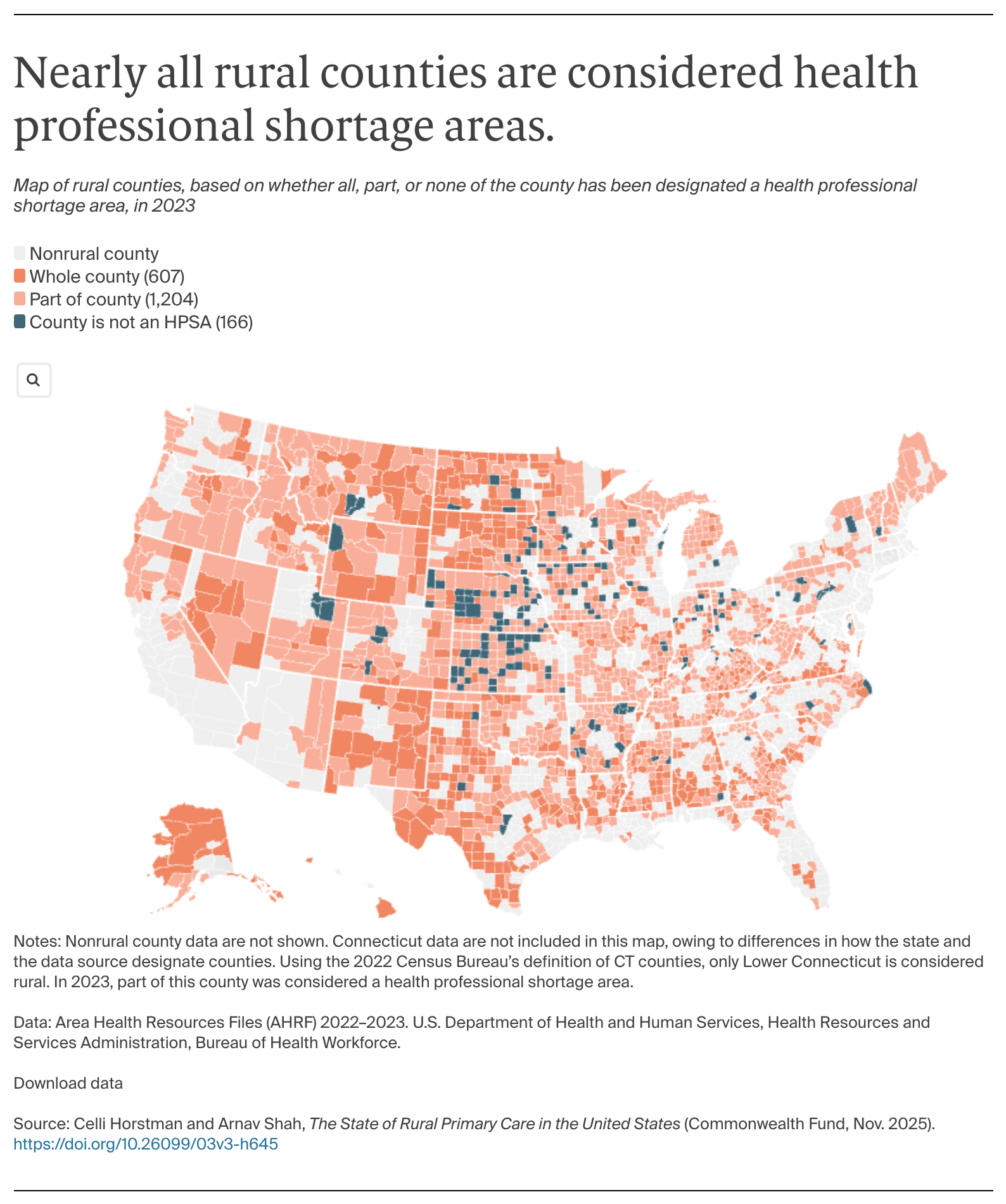

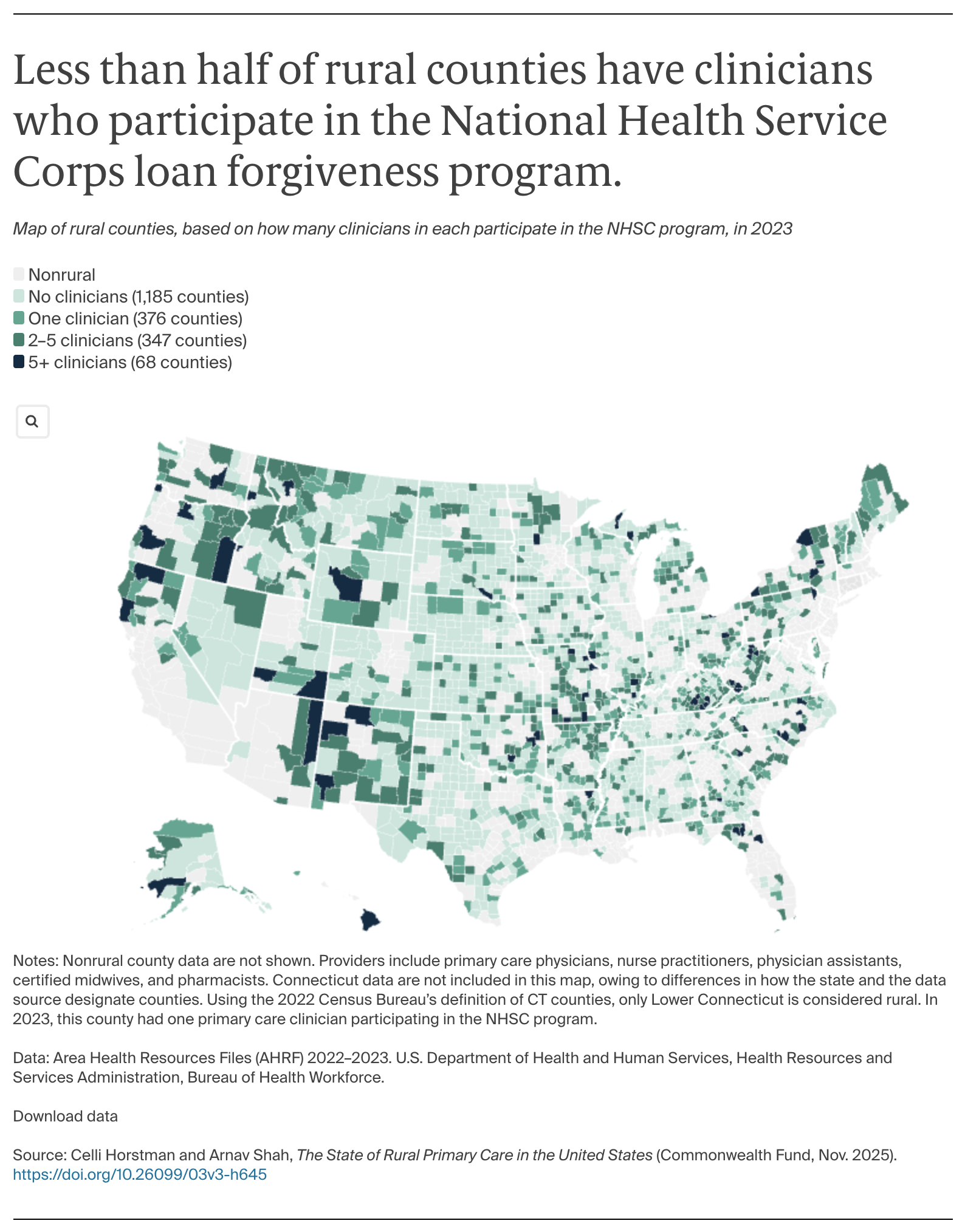

Primary care is facing existential challenges — from lower relative investment compared to specialty care to clinician burnout — which are particularly acute in rural communities.1 For the more than 60 million people, or one in five Americans, who live in rural areas, strengthening primary care requires rural-specific solutions.2

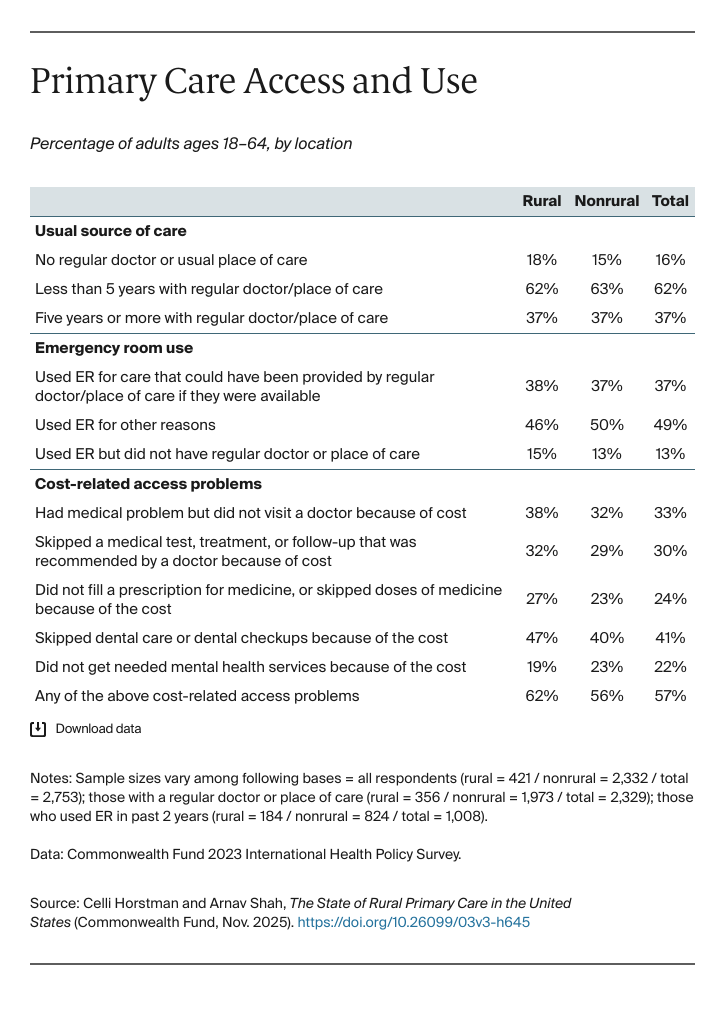

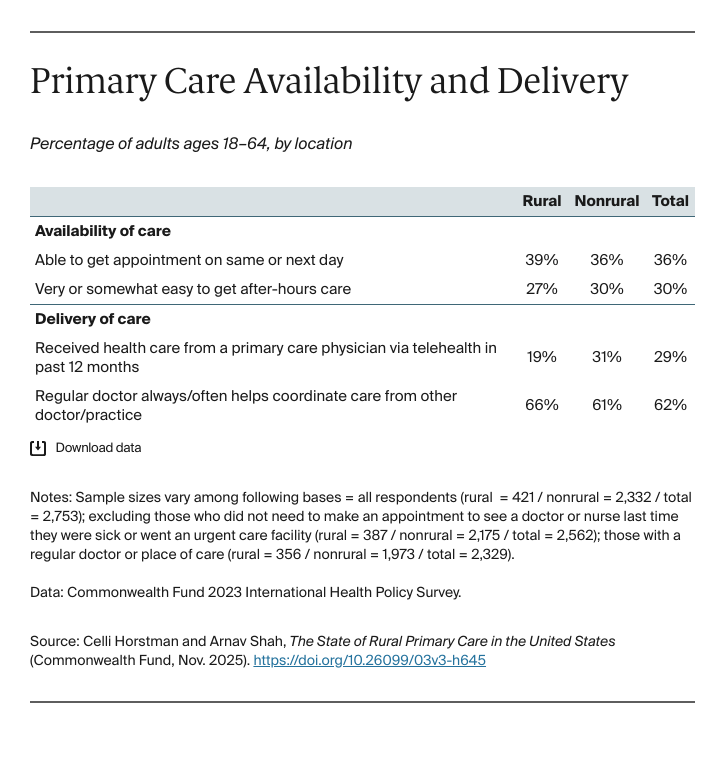

Rural clinician shortages, limited broadband internet, and a lack of public transportation in rural areas make it difficult for patients to get health care, either in person or virtually.3 These access challenges are associated with poor health outcomes, low uptake of preventive services, and overreliance on costly emergency department visits for nonurgent health needs.4

Nearly half of rural residents are uninsured or insured by public payers.5 This limited payer mix, coupled with relatively low reimbursement rates and high provision of uncompensated care compared to nonrural areas, poses challenges to the financial stability of rural primary care.6

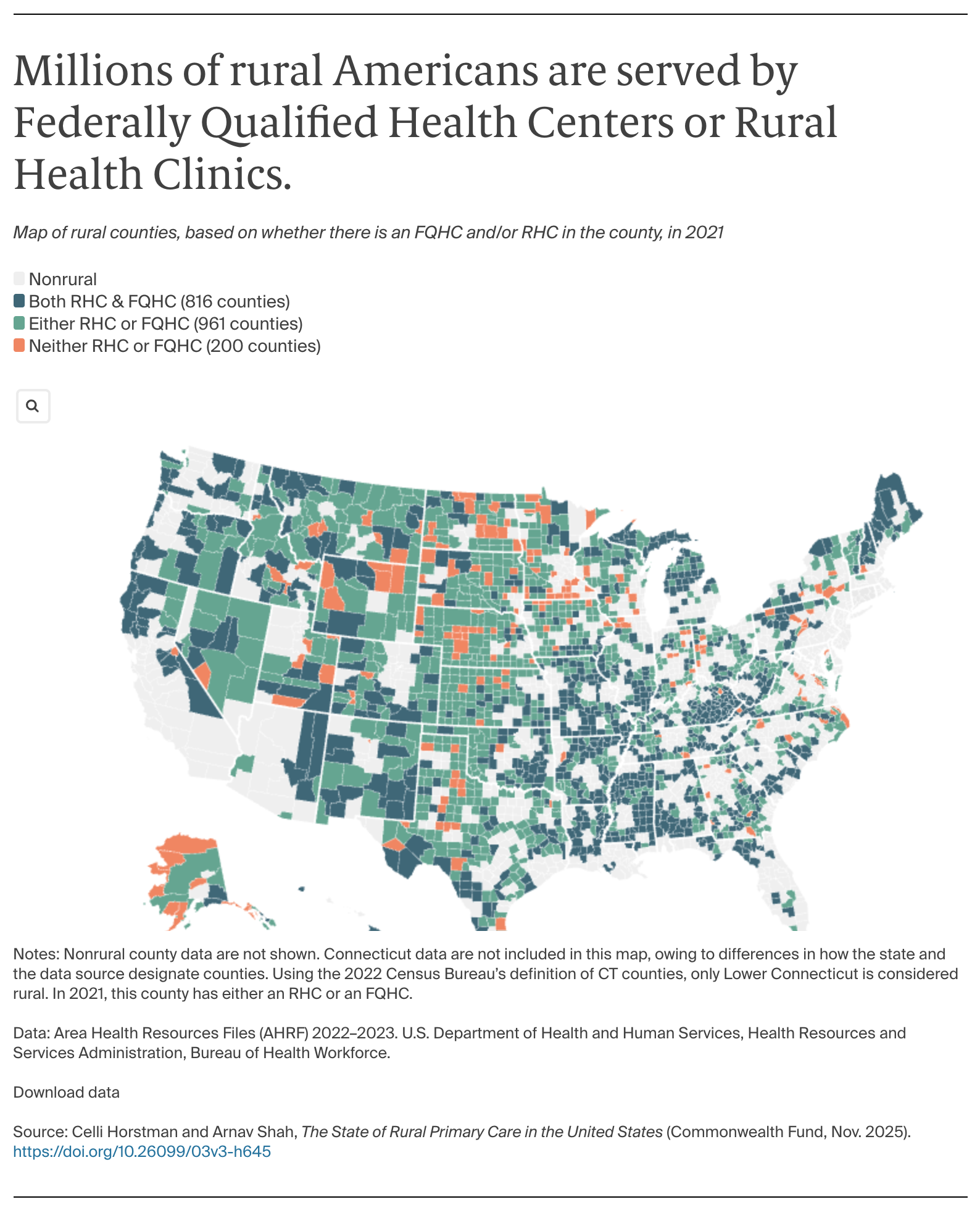

Despite these challenges, rural communities have developed innovative, place-based solutions to their health care access problems, such as mobile health units, Rural Health Clinics, and other community-directed health programs that help meet local needs.

State and congressional policymakers are also investing in rural health. For example, H.R. 1, the recently passed tax and spending law, includes the Rural Health Transformation Program, which allocates $50 billion for states over the next five years to strengthen care delivery.7 National and local strategies to improve primary care access and quality will be key to ensuring better health outcomes for rural residents.

Drawing from the Commonwealth Fund 2023 International Health Policy Survey and federal health workforce data, we describe the current state of U.S. primary care across rural America, focusing on the workforce, access to care, and care delivery. We also highlight innovative rural primary care delivery models and regional differences where data are available (see “How We Conducted This Study” for more detail).