Abstract

- Issue: Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) aimed to standardize coverage while maintaining plan choice, selecting a health plan remains a complex process for enrollees.

- Goals: To review the ACA’s policies to simplify the ways health plans vary and improve the plan selection process. We also assess subsequent changes to those policies as well as major proposals that could either improve them or increase complexity and potential dissatisfaction with private health plan coverage.

- Methods: Analysis of research, government data, proposals, final rules, and laws.

- Key Findings and Conclusion: While gains were made in structuring individual market health plan choices in the ACA, additional standards for plan design, marketing, and enrollment could improve consumer satisfaction and health care affordability. However, progress toward these goals could be undermined by future administrative or congressional changes, such as allowing alternative plan types or rolling back regulations that promote standardization.

Introduction

In the 15 years since the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted, more Americans have gained health coverage through private health plans.1 In addition to offering insurance premium tax credits, the law limited variation in private health plan design and structured the plan information and selection processes. These simplifications have prevented many consumers from enrolling in plans that have unexpected coverage gaps or excessive cost-sharing obligations, or that roll back, or rescind, coverage for needed care.2 Research continues to demonstrate that consumer welfare is enhanced through standardization of health plans and improved presentation of information or “choice architecture.”3

Yet the goal of simplifying health plan choices was challenged from the start of the ACA’s implementation and is not shared by the current administration. Today, the complexity of health insurance choices, while less than in 2010, persists, contributing to high prices and dissatisfaction.4

This brief reviews the ACA’s policies for structuring and simplifying private insurance choices along with potential options for optimizing choices and lowering costs. We offer the perspectives of individuals involved in the development and subsequent evolution of the ACA over the past 15 years.

The ACA’S High-Wire Act: Simplifying Coverage While Maintaining Choice

The Affordable Care Act came to be when few federal rules governed private health insurance, which made it difficult for many individuals and employers to determine which products met their needs.5 The designers of the law aimed to simultaneously improve consumer protections and insurer competition on price and quality while minimizing disruption.

Two types of ACA policies were intended to optimize health plan choices:

- Minimum standards for health plan comparability. Such standards limit cost-sharing exposure for families and ensure that all health plans provide a minimum value. These include policies that cap total out-of-pocket costs, prohibit annual and lifetime limits on coverage, and require coverage with no cost sharing for preventive services. The ACA also requires (or incentivizes, depending on the market) plans to cover at least 60 percent of average costs of medical care.

- Support for informed consumer choice. All health plans are required to provide a standardized “summary of benefits and coverage” outlining their terms. The law also requires standardized outreach and assistance to support consumer selection. For the individual and small-group markets, the ACA created marketplaces (also known as exchanges) to enable consumers to compare standardized plans when shopping for coverage. It also established a risk-adjustment mechanism to prevent insurers from designing their coverage in a way that enables them to cherry-pick the youngest, healthiest enrollees in a bid to boost profits.

The ACA phased in these insurance reforms to spread out the impact on premiums and to minimize disruption.6 It also created “grandfathered plans” that exempted insurers from ACA rules until they made significant changes to the plans. The ACA also recognized that large firms’ employer-sponsored insurance tended to pay for a large percentage of costs and cover a wide array of benefits, so it focused certain insurance reforms on plans in the individual and small-group markets. In other words, it limited — rather than eliminated — variation in health plan design.

While the ACA statute offered broad guardrails on insurance reform, the rules implementing it contain more details. This includes how strict or flexible the standards for plans are, as well as whether they maximize consumer protections versus consumer choices.7 Such rules have changed over time, including in 2025.

ACA Implementation, Policy Changes, and Complexity “Creep”

Soon after the ACA’s enactment in 2010, public opinion of the law was low, and the tension between improving versus maintaining health plans was high.8 To address this tension, policymakers implemented regulations that eased in reforms. For example, the law included a provision that allows insurers to delay the adoption of ACA changes for individuals continuously enrolled in their plans until the insurers make other changes.

However, the rules defining so-called grandfathered plans were considered overly permissive compared to the legislative intent.9 This loophole was widened in 2013 when the administration allowed the renewal of plans that would have been cancelled had they been compelled to meet all ACA rules (nicknamed grandmothered plans).10 While designed to be temporary, such plans persist: some individual-market enrollees remain in grandmothered plans, and, in 2020, employers reported that 14 percent of covered workers were enrolled in a grandfathered plan.11

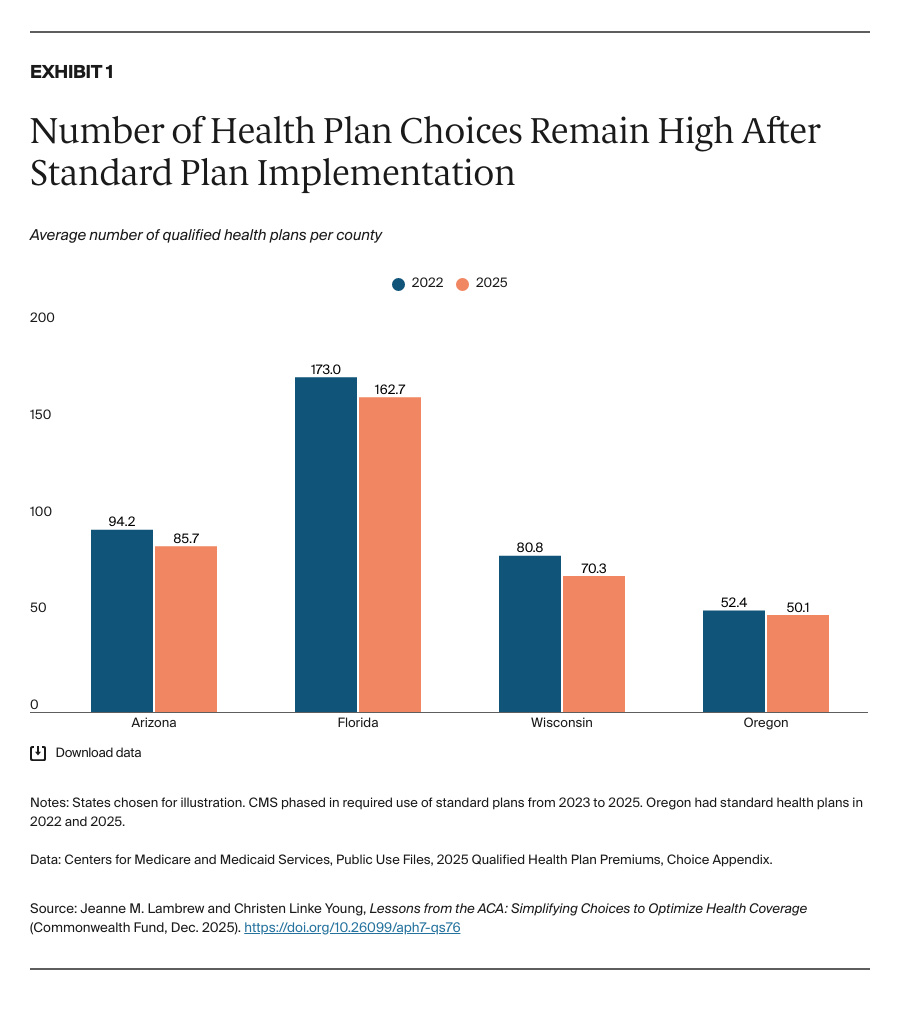

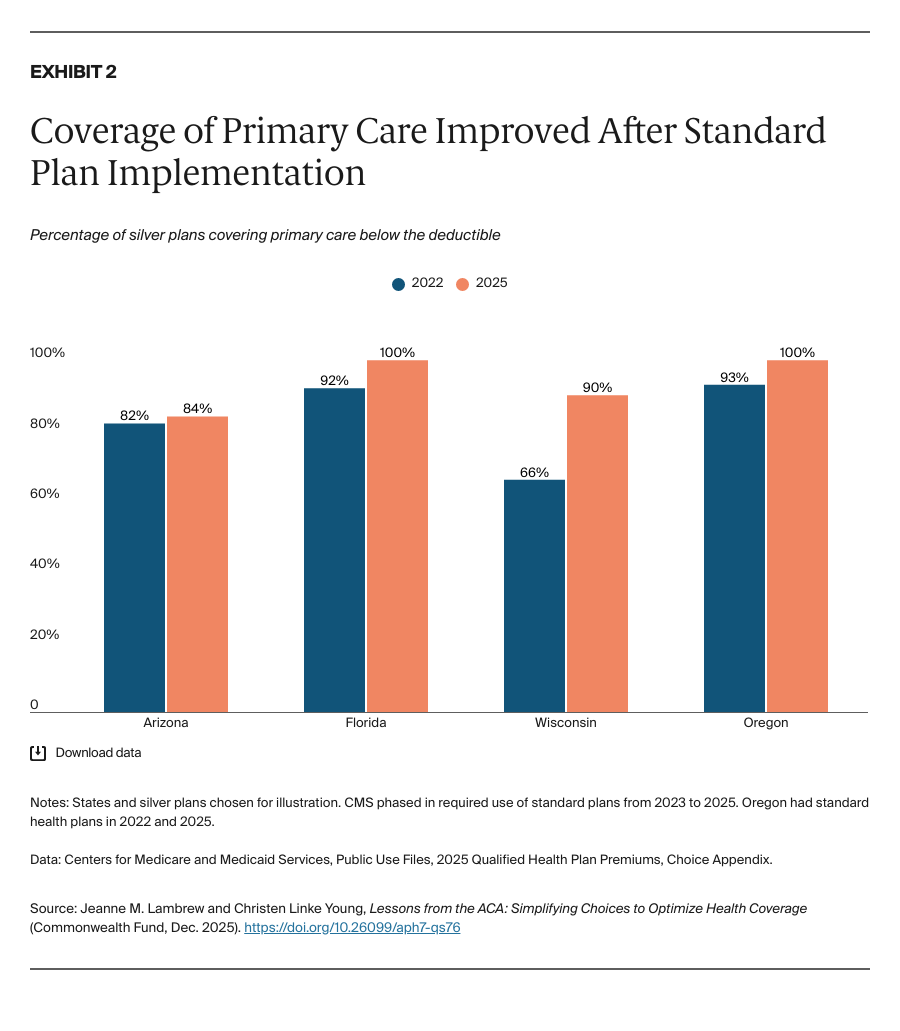

During the ACA’s implementation, other variations in health plan design, marketing, and retention practices were permitted. In response to criticism that limiting this variation would reduce the number of plan choices, the federal government took a gradual approach to standardizing cost-sharing design in the federal marketplace, piloting voluntary arrangements in 2016 and not requiring standardized offerings nationwide until 2023. After implementation, the experience of certain states suggests that concerns about fewer choices were not realized, while coverage of primary care below the deductible increased (Exhibits 1 and 2).12 Some state-based marketplaces have also limited the number of plan offerings in the interest of providing enrollees with meaningful differences in plan choices.13