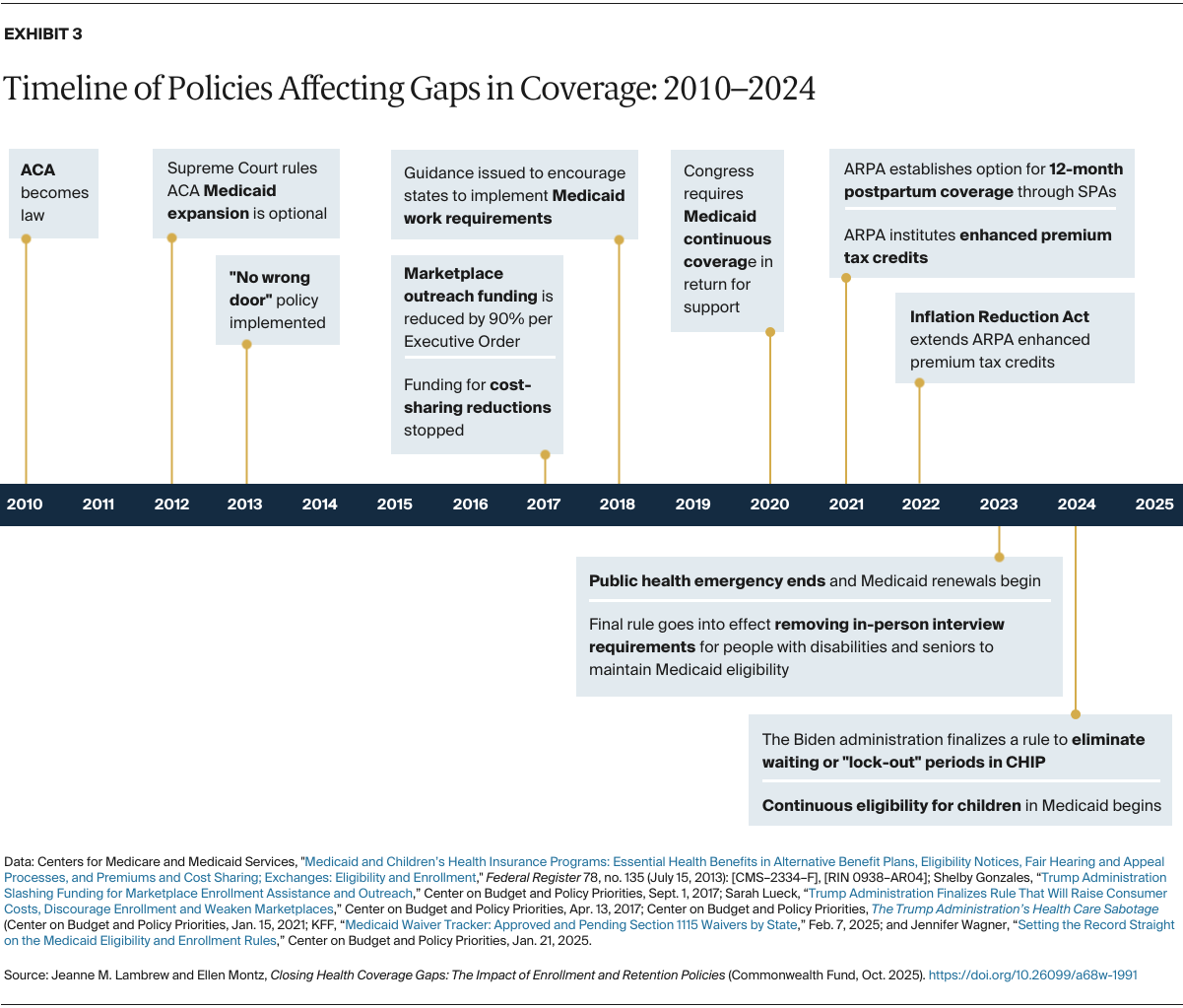

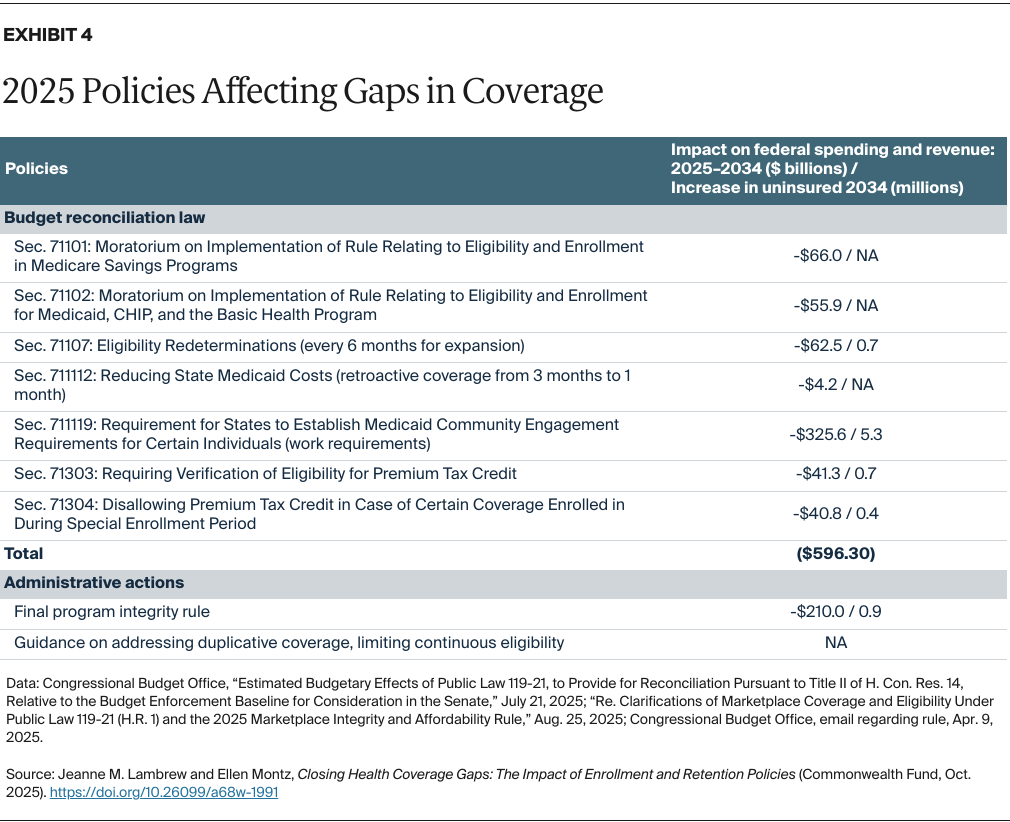

In addition to policies reducing subsidies like premium tax credits, policies included in the congressional budget reconciliation law add requirements and limit opportunities to sign up for and maintain health coverage.24 This includes mandatory work reporting requirements to access Medicaid, which have proven to increase administrative inefficiency and reduce the number of people covered without increasing employment.25 The legislation also requires states to reverify eligibility for the ACA Medicaid expansion enrollees every six months. Other policies will increase ACA marketplace premium tax credit verification requirements prior to eligibility and end automatic reenrollment through preverification requirements — all of which are likely to decrease enrollment of eligible individuals and increase insurance premiums.26

In addition to the new legislation, the Trump administration has issued rules and guidance that tighten enrollment and reenrollment processes. On June 20, 2025, it finalized a rule that will limit marketplace enrollment opportunities — by, for example, shortening the open enrollment period — increase verification requirements during special enrollment periods, and add steps to the enrollment process. By the administration’s own regulatory impact analysis, these changes will reduce enrollment by 2.8 million people.27 Further guidance issued on July 17, 2025, will disenroll individuals who appear to be enrolled in Medicaid and marketplaces after 30 days’ notice and end approval of demonstration waivers that allow for continuous Medicaid eligibility.28

Policies to Get and Keep People Covered

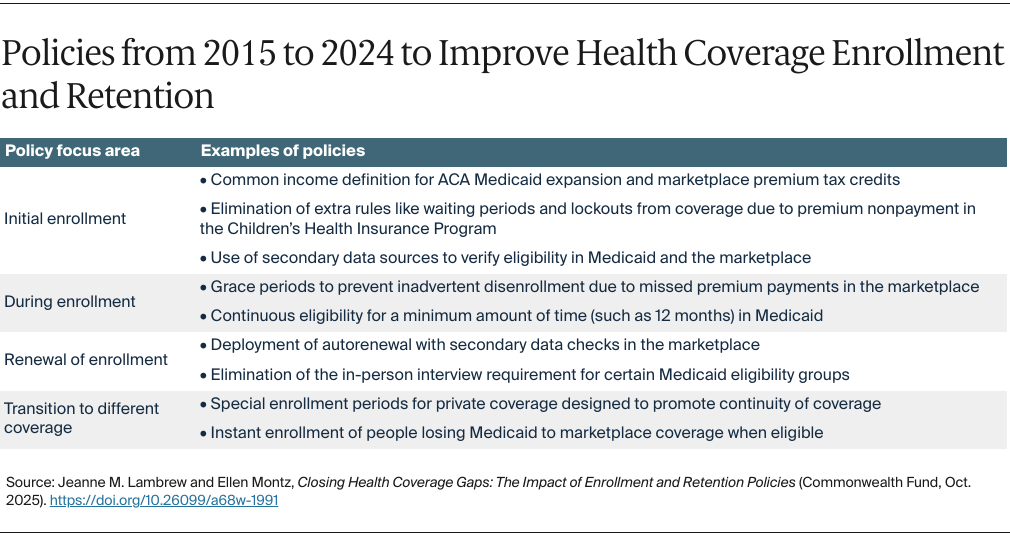

Policymakers and program administrators have three main pathways for improving health coverage enrollment and retention.

Making Eligibility Continuous for People with Low Incomes

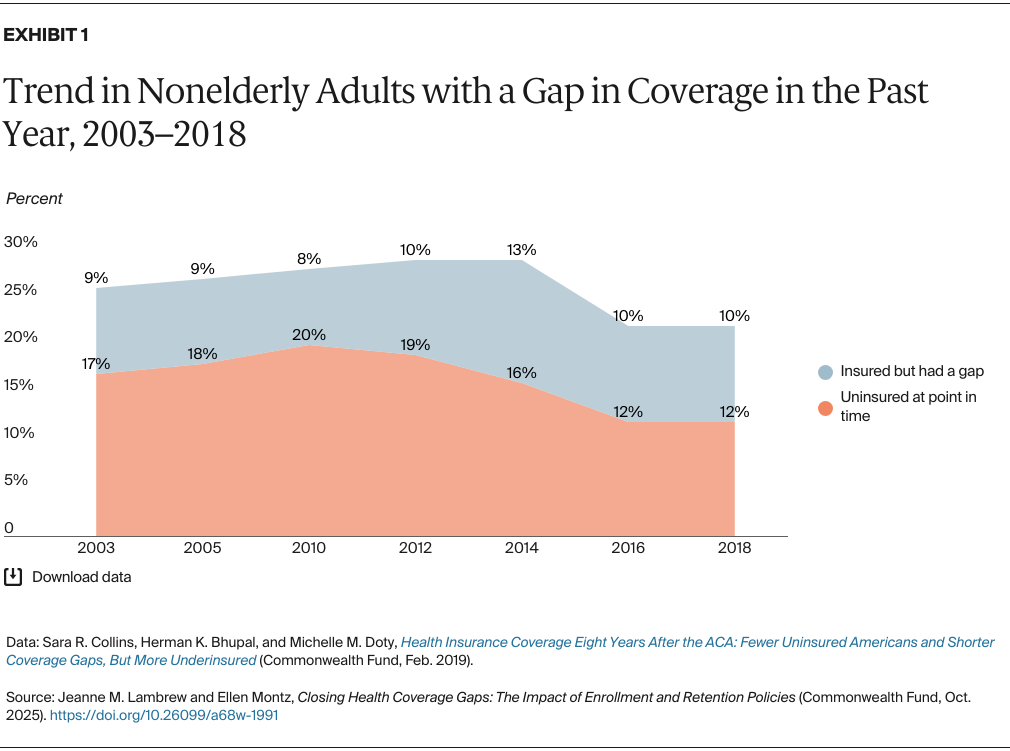

People with low incomes tend to have greater income fluctuations and are more likely to have breaks in coverage than those with high incomes.29 Maintaining their coverage may be the most important option to limit churning of coverage. This could be addressed in two ways:

- Extending Medicaid’s continuous coverage requirement to adults. One analysis found that providing 12 months of continuous eligibility for Medicaid to nonelderly adults would increase enrollment by over 450,000 and save households and employers $2 billion and reduce total health care spending by $1.8 billion annually, all at a relatively low cost to the public.30

- Autoenrolling people transitioning from Medicaid to the marketplace. Eligible people losing Medicaid due to increased income could be automatically enrolled into marketplace plans until the next open enrollment period, with no reconciliation of the tax credit for that year. This would prevent coverage loss during transitions while ensuring people transitioning from Medicaid have coverage and are treated like other enrollees starting in the next annual renewal process. With simpler eligibility rules, autoenrollment could have broader applications to low-income people or even all eligible residents.31 Designing the system to check eligibility using secondary data sets can address concerns about fraudulent or erroneous enrollment.

Simplifying and Aligning Enrollment Rules for Different Coverage Options

Policymakers could align rules for eligibility, verification, and timing of coverage to reduce coverage gaps while ensuring program integrity. Examples of such policies include:

- Using the same definitions for eligibility in the marketplace and Medicaid. This includes what counts as income, family compensation, and immigration status. While coordination was advanced through the ACA and subsequent policies, additional alignment would help prevent duplication and inadvertent gaps in coverage.

- Filling in eligibility gaps in the marketplace and Medicaid. Given low-income workers often struggle to afford employer coverage, eliminating the ACA’s “firewall,” which prevents workers with affordable employer-sponsored insurance from receiving premium tax credits, could help bridge coverage gaps. For example, the 2015 policy for qualified small business health reimbursement accounts (HRAs) could be amended to ensure workers getting employer funds to buy marketplace coverage receive either the tax benefit of the HRA or the tax credit, whichever is more beneficial to them.32 Additionally, eliminating the lower eligibility limit (100% of FPL) for the premium tax credit while maintaining the ACA’s Medicaid expansion could fill the coverage gap created by some states’ inaction.33 An estimated 1.4 million people are in the coverage gap, making this arguably the most effective of the proposals at reducing uninsurance.34

- Extending the end date of coverage to allow more time to enroll in new coverage. Public and private coverage, including employer contributions for premiums, could continue until the first day of the month that comes 30 days or longer after termination, limiting disruptions associated with changing types of insurance. Preventing disenrollment is simpler than speeding up new enrollment. Coupled with improved efficiency in eligibility determinations for new coverage, extending coverage could limit the need for “presumptive eligibility” in Medicaid, which requires some degree of duplicative work. It also could prevent coverage gaps given the recent budget reconciliation law that changed the retroactive Medicaid eligibility limit from three months to one month.

Creating a Single, Nationwide Eligibility System

The HealthCare.gov platform, which currently serves as the marketplace platform in 31 states, could be adapted for:

- Determining and renewing Medicaid eligibility. HealthCare.gov already performs this function for a subset of states and enrollees, and expanding this capacity would eliminate the need for each state to develop its own system for people whose eligibility is the same in all states.

- Replacing state-based marketplaces. States could retain functions that facilitate enrollment as well as add on to the federal system, but platforms that are not optimally designed for seamless coverage determinations could be replaced.

A single, nationwide eligibility platform would go a long way toward the goal of “no wrong door to coverage.” It also is preferable to outsourced enrollment systems whose complexity exceeds consumer benefits.35

Conclusion

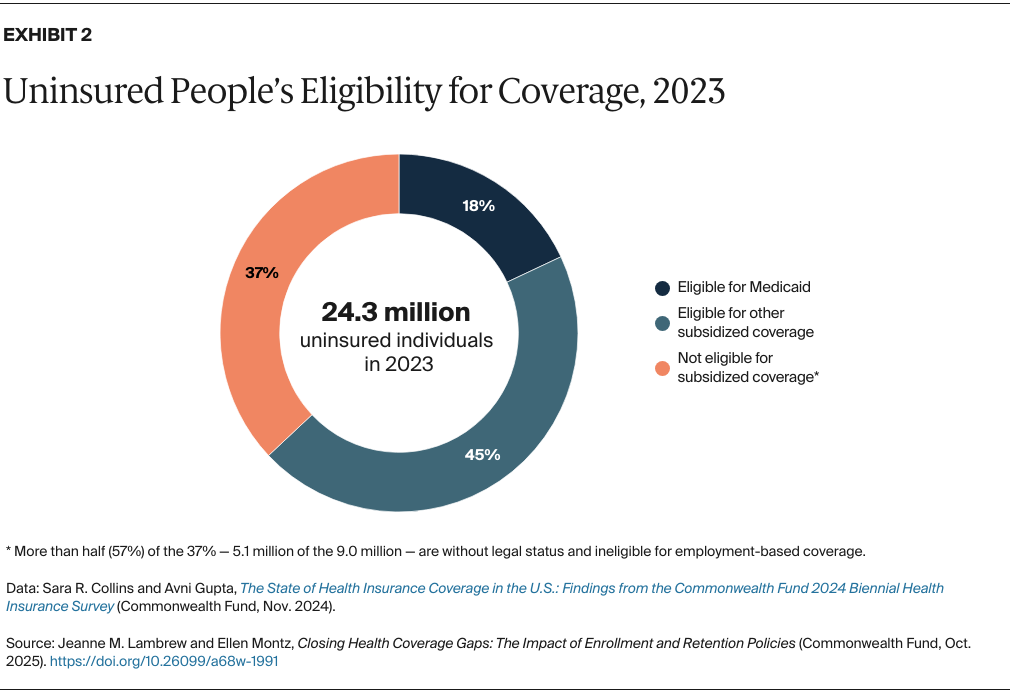

Enrolling people in health coverage, and keeping them covered, requires particular attention in a system with multiple sources of health insurance. Alongside aligning eligibility policies and systems, policies that make coverage affordable and encourage people to get and use coverage are critical. Recent changes have added complexity to eligibility policies and systems with the stated goal of increasing program integrity.

However, these changes rest on the assumption that additional “hoops” for enrollment will be effective, with little proof, while discounting the cost of eligible individuals losing coverage in the process. Millions of uninsured people could be covered today with improved enrollment and retention systems without adding to waste, fraud, or abuse.