In 2026, Affordable Care Act (ACA) premiums increased by more than 20 percent, in large part because insurers believe they are facing increased risk due to the expiration of enhanced premium tax credits and other policies. A new Urban Institute report finds that marketplace benchmark premiums (i.e., the second-lowest-cost silver plans) have increased by an average 21.7 percent.1 This increase is significantly larger than the 6 percent to 7 percent projected increase in the employer-sponsored insurance market. This has led to claims that the ACA is a disaster, financially out of control, unsustainably expensive, and wasteful. In reality, the 2026 premium increases are an aberration, far above those observed in recent years.

The 21.7 percent increase refers to the changes in the full premiums, which reflect several factors. There are related but largely separate issues affecting the “net” premium prices (i.e., the amount paid by enrollees after government subsidies are applied), including the expiration of the more generous enhanced premium tax credits, which were a major issue behind the recent government shutdown. The reversion back to the original, less-generous ACA tax credits will increase net premiums at each income level, regardless of the level of full premiums.

Our colleagues have estimated that the expiration of premium tax credits will result in 7.3 million fewer marketplace enrollees and an increase of 4.8 million Americans without insurance. In addition, another study estimated that changes in regulations and in H.R. 1 would result in an overall decrease in marketplace enrollment of 5 million and an increase in the number of uninsured by 2.7 million. There will not only be a reduction in enrollees but most likely a less healthy population, meaning more risk for insurers.

The 21.7 percent increase in ACA premiums likely reflects the same medical care cost trends that have caused premiums in employer-sponsored plans to increase by about 6 percent to 7 percent. These include higher wages for health care providers, price increases due to consolidation of hospital systems, and increased intensity in utilization of certain treatments like new weight-loss drugs, among other factors. The expected increase in health risk because of shrinking enrollment following the expiration of enhanced premium tax credits accounts for another 4 percent to 6 percent of the increase. This leaves another 9 percent to 10 percent. We suspect this is due to other factors that reduce enrollment, including H.R. 1, the CMS Integrity rule, cuts in assistor and outreach spending, and general uncertainty in the market. Because of the higher risk and uncertainty, some insurers have dropped out of the ACA market, but most continue to participate and charge higher premiums. We estimate that as many as 21 states lost at least one insurer; Aetna has dropped out of the market altogether.

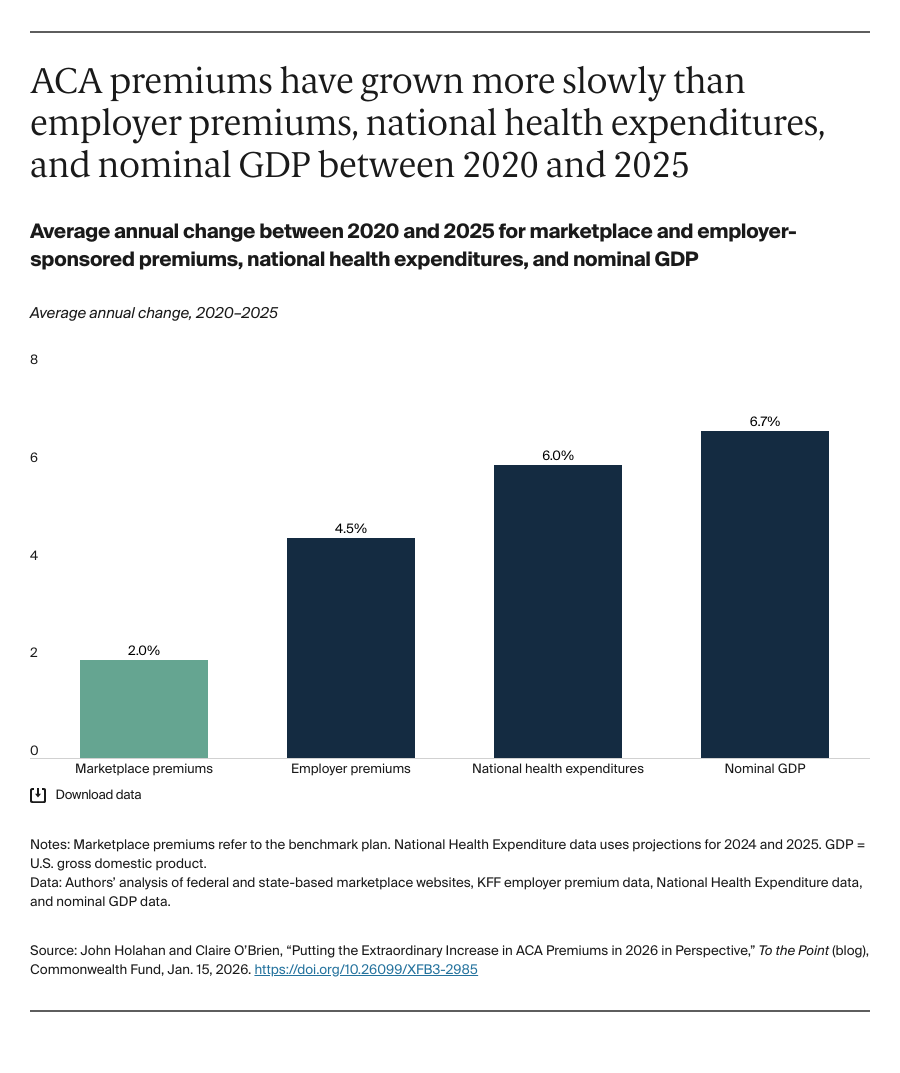

ACA premiums grew more slowly (2.0% annually) than employer premiums (4.5%), national health expenditures (6.0%), and gross domestic product (6.7%) between 2020 and 2025. As we have shown, the level of ACA premiums prior to 2026 were lower than those in employer and small-group markets, by 15 percent and 23 percent, respectively. This analysis controlled for differences in actuarial value of plans (i.e., richness of benefits), utilization, and the need for marketplace premiums to finance cost-sharing reductions. We have also shown that the ACA does not subsidize rich insurance plans; deductibles and out-of-pocket costs are high. We showed that deductibles average $5,000 for silver plans and $7,500 for bronze plans; out-of-pocket maximums were between $9,000 and $10,000.