The progress made during this period suggests that it is possible to reach near-universal coverage if enhanced subsidies are combined with Medicaid expansion, improved enrollment and retention systems, and other state efforts. States that have expanded Medicaid, run their own marketplaces, and adopted their own individual responsibility provisions have 6 percent higher coverage rates than states adopting none of these policies.23 Their coverage rate is comparable to countries with universal coverage.24

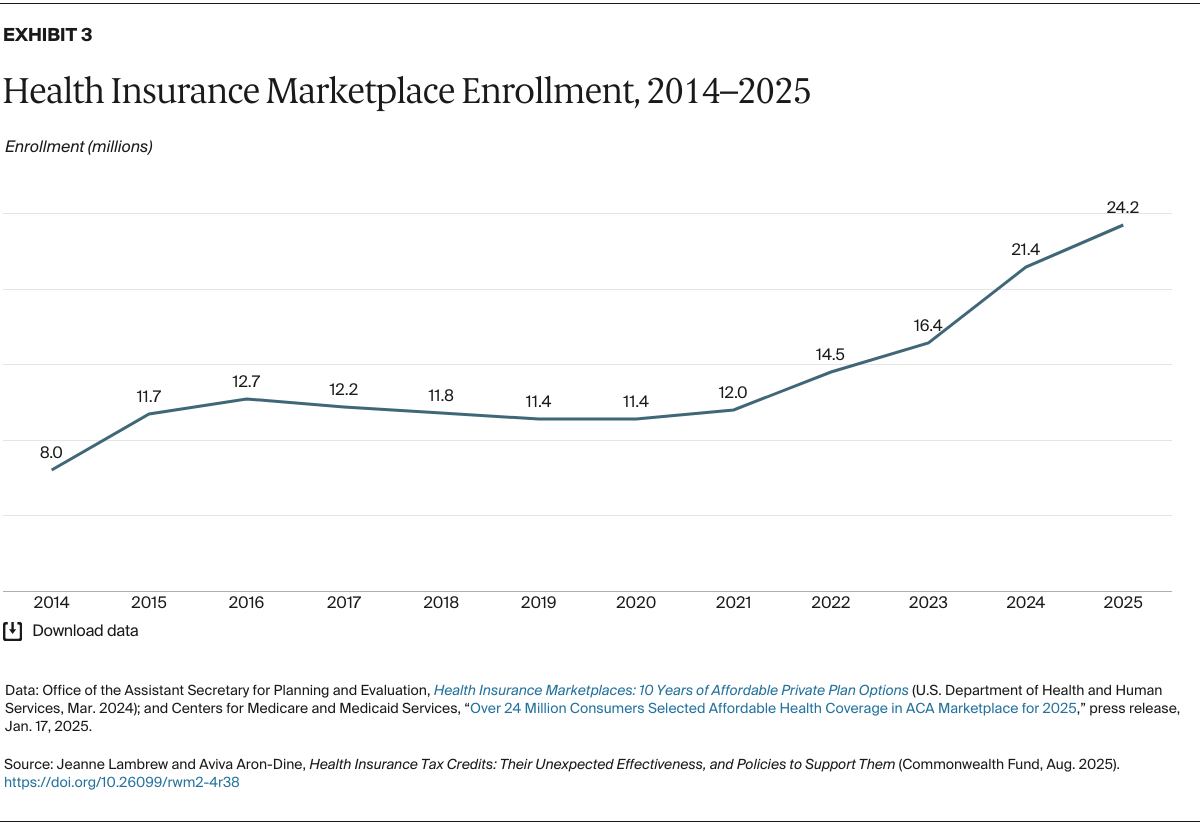

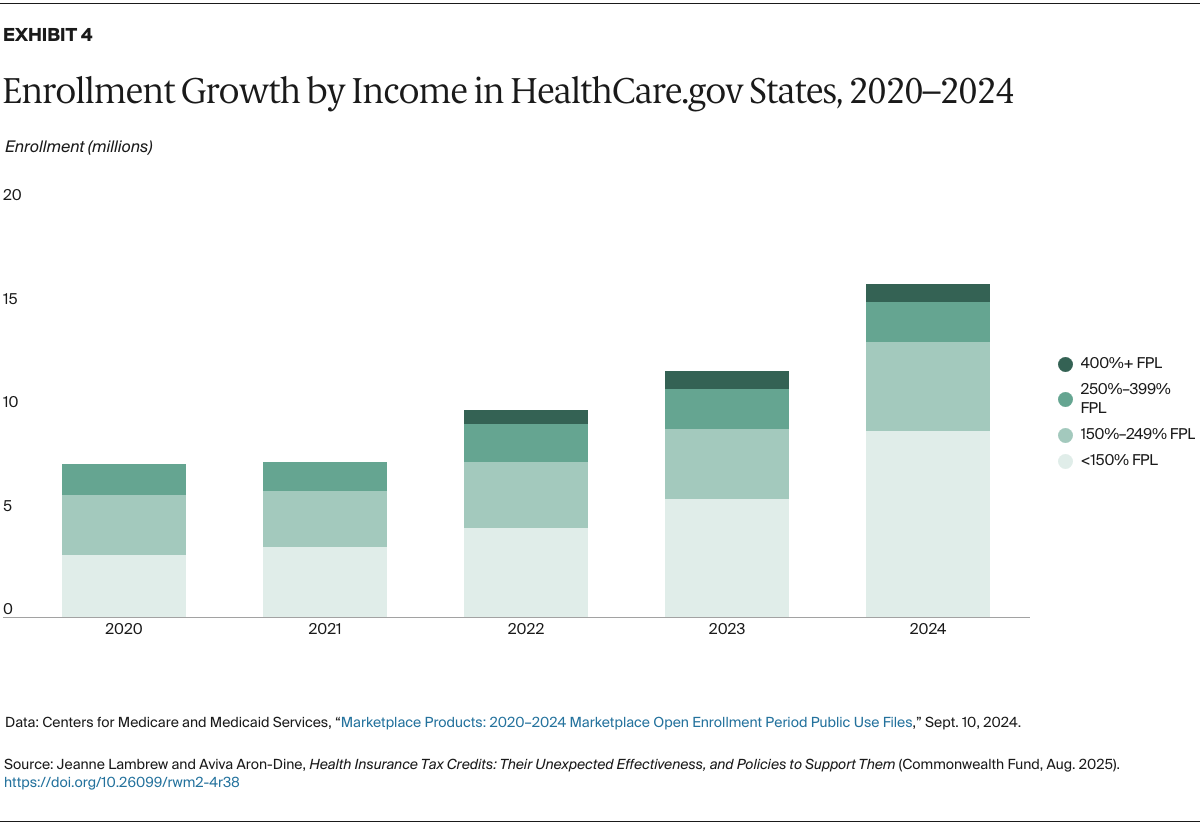

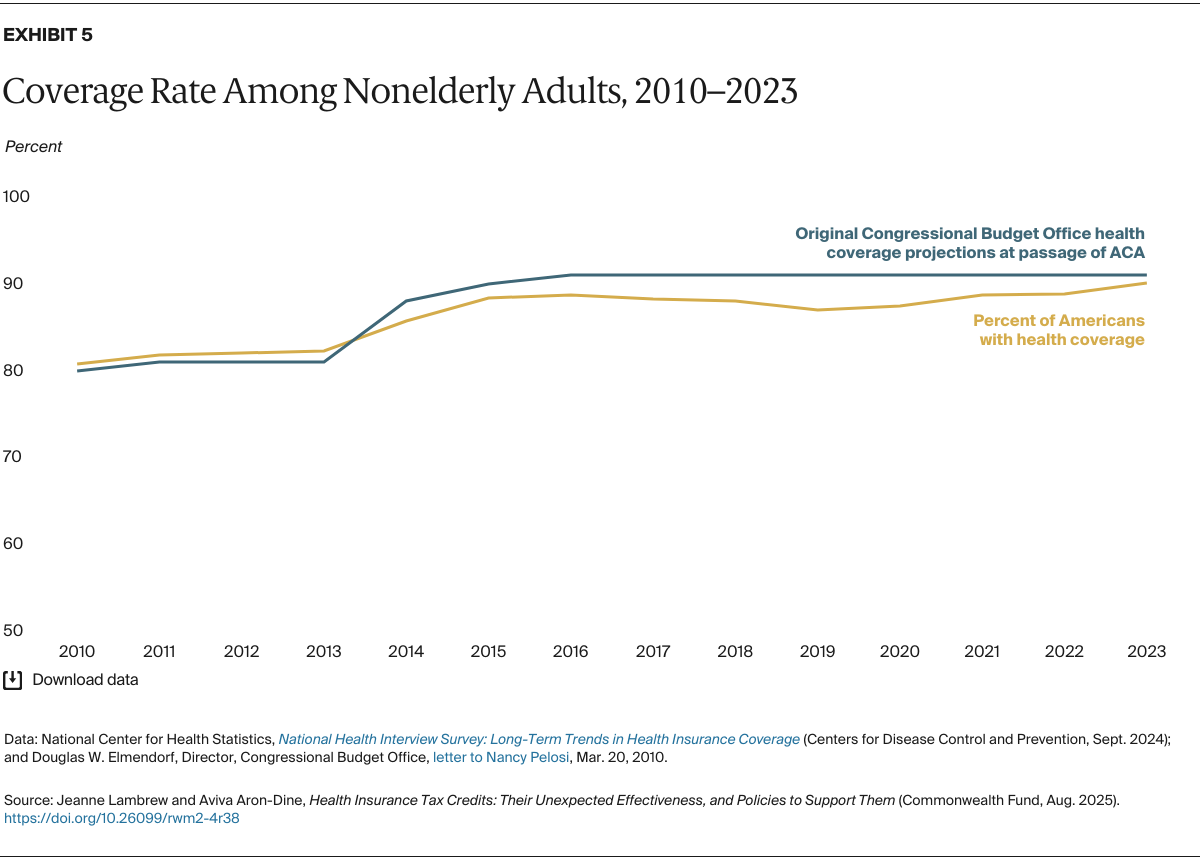

As with enrollment changes, health coverage increases since 2020 substantially exceed the predicted effect of the enhanced premium tax credits, with the caveat that other factors affect coverage as well. In the first half of 2024, there were 7.0 million fewer nonelderly uninsured Americans compared to 2019. Prior to passage of the American Rescue Plan in 2021, the CBO estimated that the premium tax credit changes would lower the number of uninsured by 1.3 million.25 After the tax credit provisions were extended in the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022, the CBO projected that making the changes permanent would reduce the number of uninsured by 2.2 million.26 Most recently, it projected that continuing the changes would reduce number of the uninsured by 4.2 million.27 Others project that extending the tax credit changes would lead to reductions in the number of uninsured, from 4 million28 to 5.4 million.29

Two Paths: Improving or Limiting the Efficacy of Tax Credits

The unexpected success of the ACA premium tax credits demonstrates the importance of financial assistance in expanding coverage. The most important near-term decision policymakers face is whether to maintain the changes from the American Rescue Plan and Inflation Reduction Act that addressed the original shortcomings of the premium tax credit policy. Numerous analyses project this would positively affect coverage and affordability, at a federal cost that is comparable to other forms of health subsidies.30 As of its August 2025 recess, Congress has not extended the enhanced premium tax credit, which is a priority for maintaining gains.

Additionally, policymakers could consider two other changes to premium tax credits to advance the affordability of private health insurance.

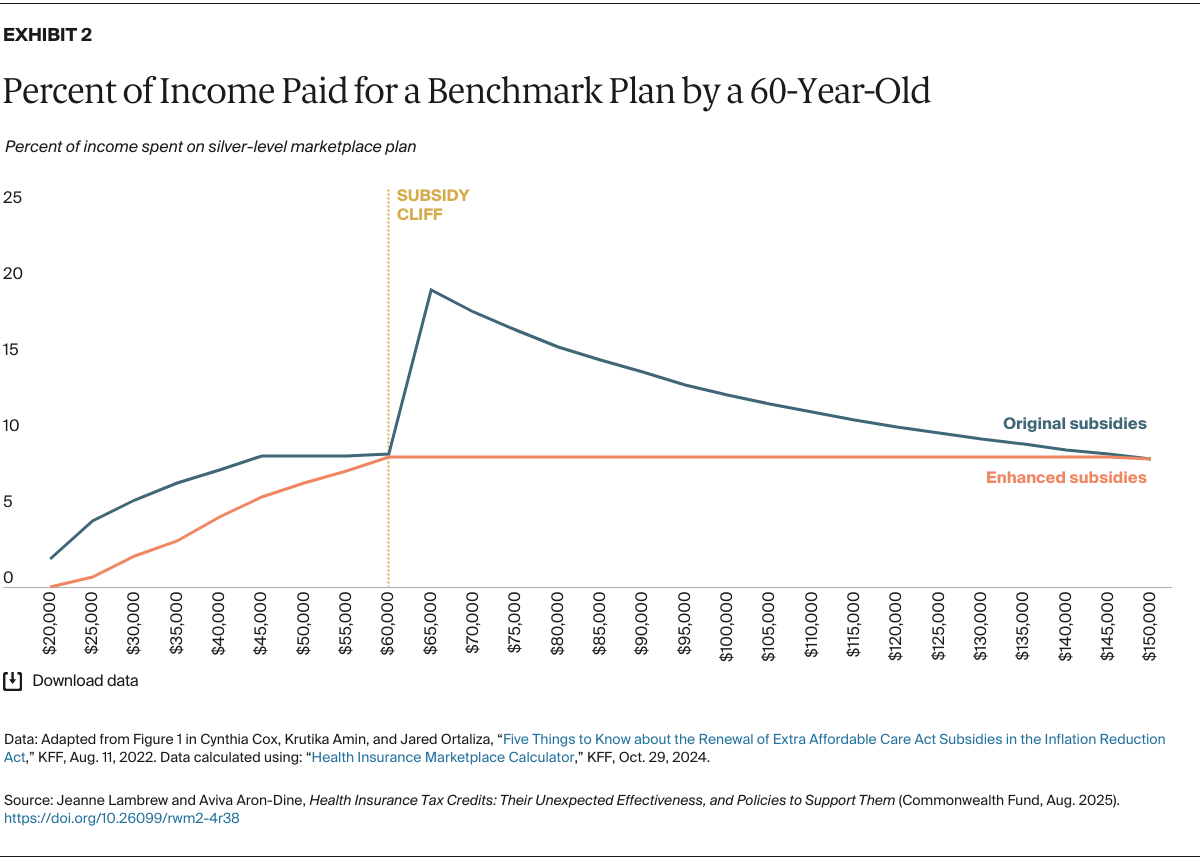

Directly link the premium tax credit to a more generous health plan. The consequence of the first Trump administration’s ending federal payment for cost-sharing reductions is that the premiums for the silver plans (which are used as the benchmark to determine the amount of tax credit enrollees receive) have been increased, or “loaded,” to pay for this otherwise unfunded mandate. In effect, silver loading has increased the actuarial value (meaning the percentage of medical costs the plan pays) of benchmark coverage in most states from 70 percent to about 85 percent of health expenditures,31 improving affordability and increasing coverage.

But silver loading has some downsides compared to directly increasing the value of benchmark coverage: There is variation in implementation across states, and the resulting pricing structure may lead to overenrollment in lower-value bronze plans.

Congress could change the actuarial value of the silver-plan benchmark coverage from the current 70 percent to 80 percent or 85 percent of health expenditures and return to an explicit payment to insurers for cost-sharing subsidies.32

Remove the premium tax credit’s lower eligibility limit. In 2021, Congress considered legislation that would have established subsidized coverage for people with incomes below FPL in states that have not adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion. In developing this proposal, policymakers debated whether providing coverage for this group through the ACA marketplaces would meet the needs of low-income enrollees, or whether it was necessary to create a federally administered Medicaid plan for this group, a far more complex undertaking. The experience of the past several years indicates that marketplace coverage, with zero-premium plans and improved enrollment procedures, is a successful approach to covering people at or near FPL.

Removing the lower-income eligibility limit for premium tax credits could provide a simple approach to this currently intractable gap in the U.S. coverage system, which is the 3 million to 5 million poor Americans in states that have not expanded Medicaid who are currently ineligible for tax credits.33 However, as with the 2021 proposals, legislation also would need to incorporate strong incentives to prevent states that have already expanded Medicaid through the ACA from dropping their expansions and relying on the federal program, especially in light of the financial burdens placed on expansion states by the recently enacted budget reconciliation law (e.g., extra limits on provider taxes).34

Proposals That Could Limit the Efficacy of Premium Tax Credits

The Republican-led Congress and the Trump administration have both made a number of major policy changes that will affect premium tax credits in 2026 and beyond. With the rationale of reducing federal spending and fraud, they have limited eligibility for and the value of premium tax credits. The final program integrity rule lowers the value of premium tax credits by changing the indexing formula.35 And, the reconciliation law changes enrollment and reenrollment policies in ways that will make it harder for eligible people to access premium tax credits while also eliminating premium tax credit eligibility for certain lawfully present immigrants.36 CBO has estimated that the final rule by itself would increase the number of uninsured by 1.8 million.37 It projects the reconciliation law, including its Medicaid and marketplace changes, would increase the number of uninsured by 10 million.38 Taken together, the rule changes, law changes, and lack of extension of enhanced subsidies could reduce marketplace enrollment around half and increase premiums by 7.0 percent to 11.5 percent.39

Additional proposals that were not included in the reconciliation law could further limit the effectiveness of premium tax credits.

Ending zero-premium plans. One analysis estimated that more people are enrolled than are eligible for premium tax credits, attributing this in part to setting the value of the premium tax credit so that the lowest-income enrollees may pay no out-of-pocket premium induces fraudulent enrollment.40 While the analysis has been disputed, zero-premium plans do make it easier for agents and brokers to fraudulently enroll eligible individuals; changes to prevent this abuse have been implemented or proposed.41

However, overwhelming evidence underscores that even relatively small premiums are a barrier to enrollment.42 The current policy allowing zero-premium plans has increased enrollment of otherwise eligible but uninsured people. This not only gives them the security of health coverage but also improves the risk pool for all enrollees, lowering premiums. Continuing such tax credits for low-income enrollees would maintain this positive impact on coverage.

Ending silver loading without compensating changes. A provision passed in the House but excluded from the final budget reconciliation legislation would revert to the pre-2018 approach to cost-sharing reduction payments. As described earlier, the current policy of silver loading has improved the value of tax credits, so that eliminating silver loading without commensurately increasing the value of the credit would not only shift cost to middle-income people but also reduce coverage.

Expanding tax spending for health accounts. Conservatives, including the Republican House Freedom Caucus,43 support using taxpayer dollars to subsidize health savings or reimbursement accounts. The House-passed version of the budget reconciliation bill included over a dozen sections with such policy changes.44 Research and experience suggest the health accounts are not a replacement for health coverage and tend to drive up unnecessary health spending.45 Such accounts also disproportionately benefit wealthy rather than middle-income people and disqualify middle- and low-income people from premium tax credits. In a time of fiscal constraint, extending and improving premium tax credits for middle-income people would have a broader benefit than funding the expansion of such accounts.

Conclusion

Lessons from the first 15 years of the Affordable Care Act suggest that the health insurance marketplace premium tax credits have been more durable and effective than anticipated. These subsidies could serve as a foundation to address other problems affecting health coverage in the U.S., such as underinsurance from inadequate coverage and the Medicaid coverage gap that leaves many uninsured in nonexpansion states. That said, policies adopted in recent months by the Trump administration and Congress will reverse much of the past decade’s progress. Failing to extend current enhanced premium tax credits, otherwise lowering tax credit values, and shifting taxpayer dollars to savings accounts rather than coverage would further erode coverage gains. The short-term federal financial gain of such proposals could lead to higher federal costs by creating greater numbers of uninsured, requiring more government funding for uncompensated care, and worsening health outcomes in the United States.