While the United States spends more of its gross domestic product on health care than other high-income countries in the world, Americans do not have more affordable or more accessible care.1 Life expectancy in the U.S. is also lower compared to peer countries, and rates of avoidable deaths are higher.2

The predominance of fee-for-service payment in the U.S. is seen as a major contributor to this incongruity. Because health care providers are paid for each service they deliver, fee-for-service incentivizes the delivery of a high volume of services, regardless of their value, efficiency, or quality. Value-based care — which ties payments to patient outcomes rather than the number of services — is a potential tool for improving care quality and equity while also reducing costs.3

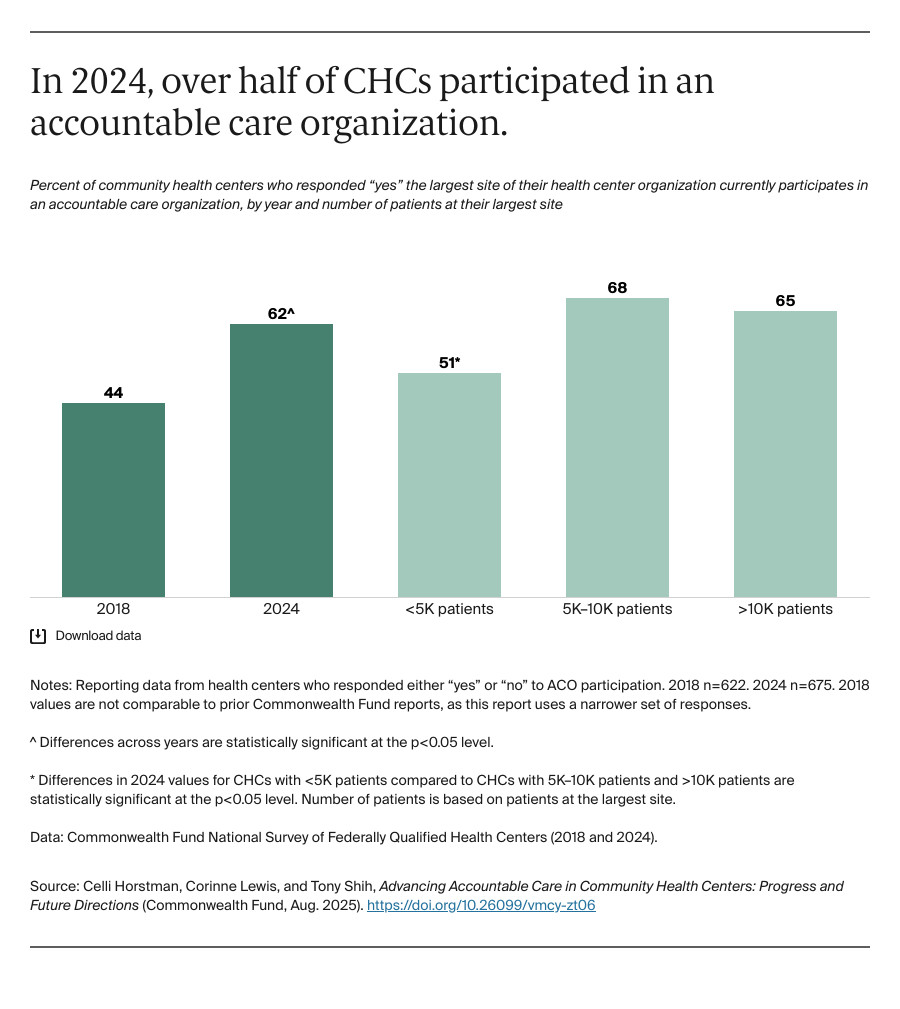

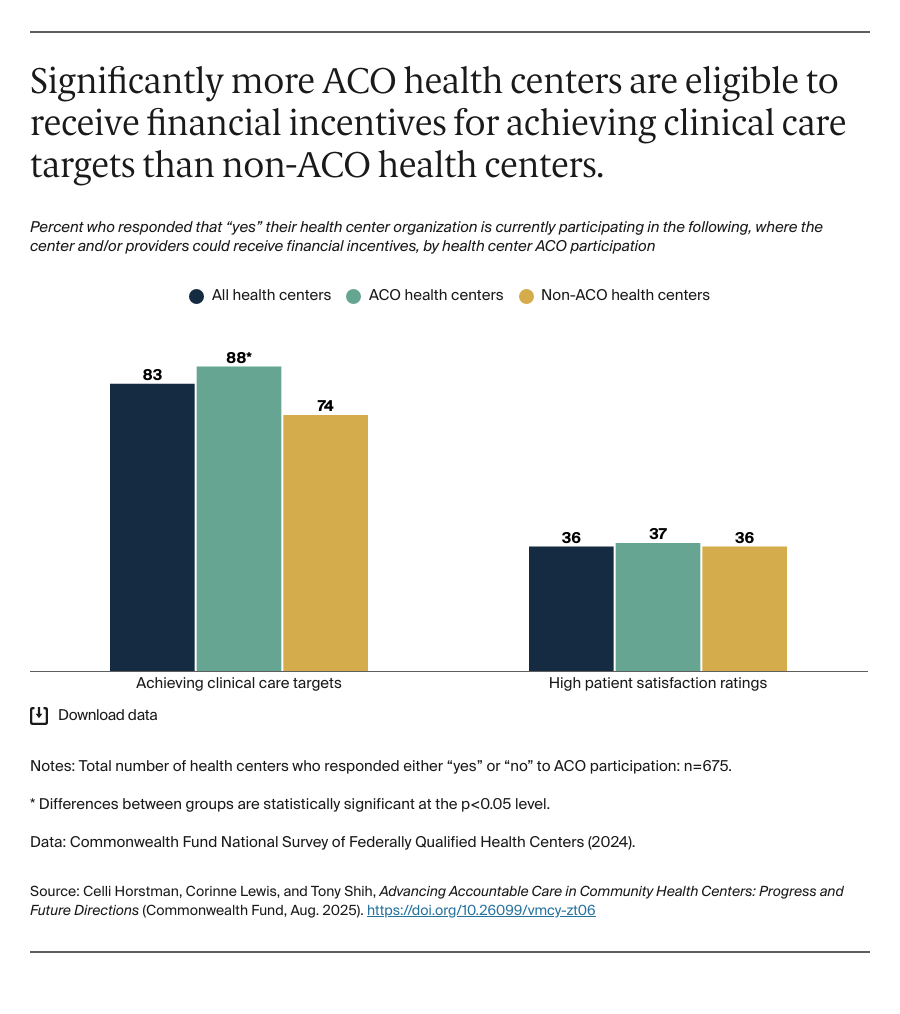

One of the most promising models of value-based care with the highest participation among health systems and providers is the accountable care organization (ACO).4 ACOs are networks of providers that join together to assume responsibility for the cost and quality of care delivered to their patients. If they are successful in improving care delivery without increasing costs, providers can receive financial rewards from payers. Many types of providers participate in ACOs, including community health centers (CHCs), which predominately serve low-income and publicly insured or uninsured patients.

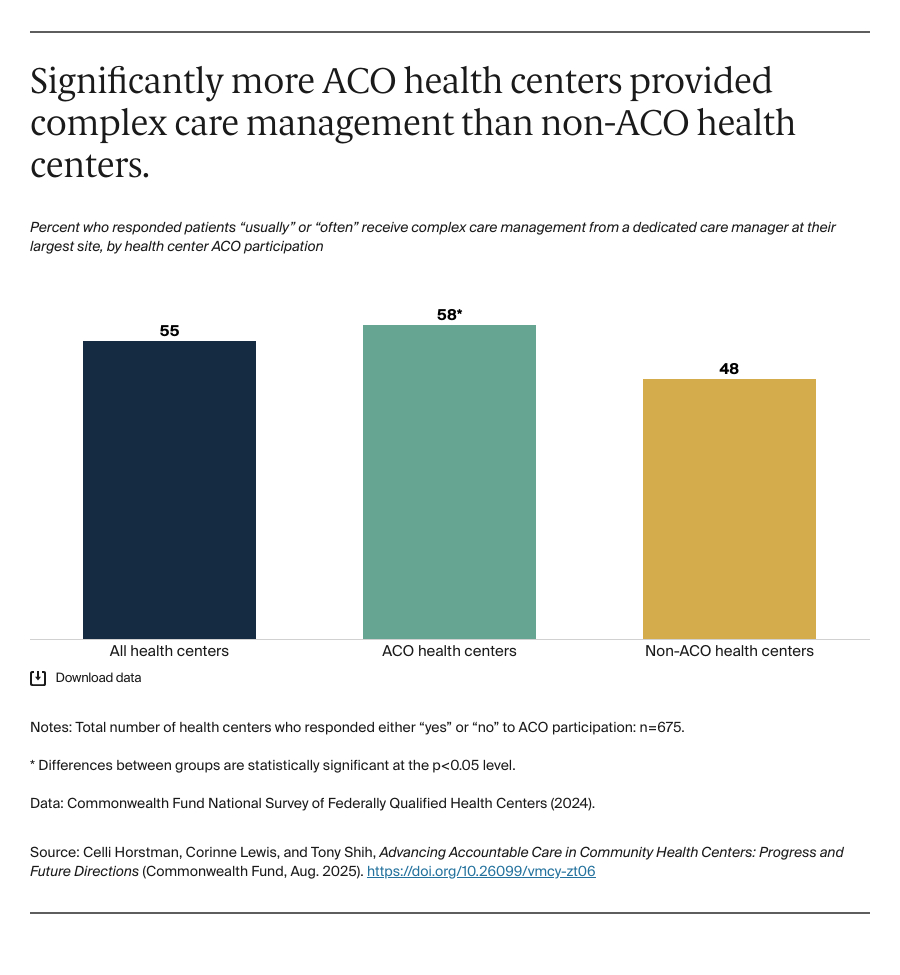

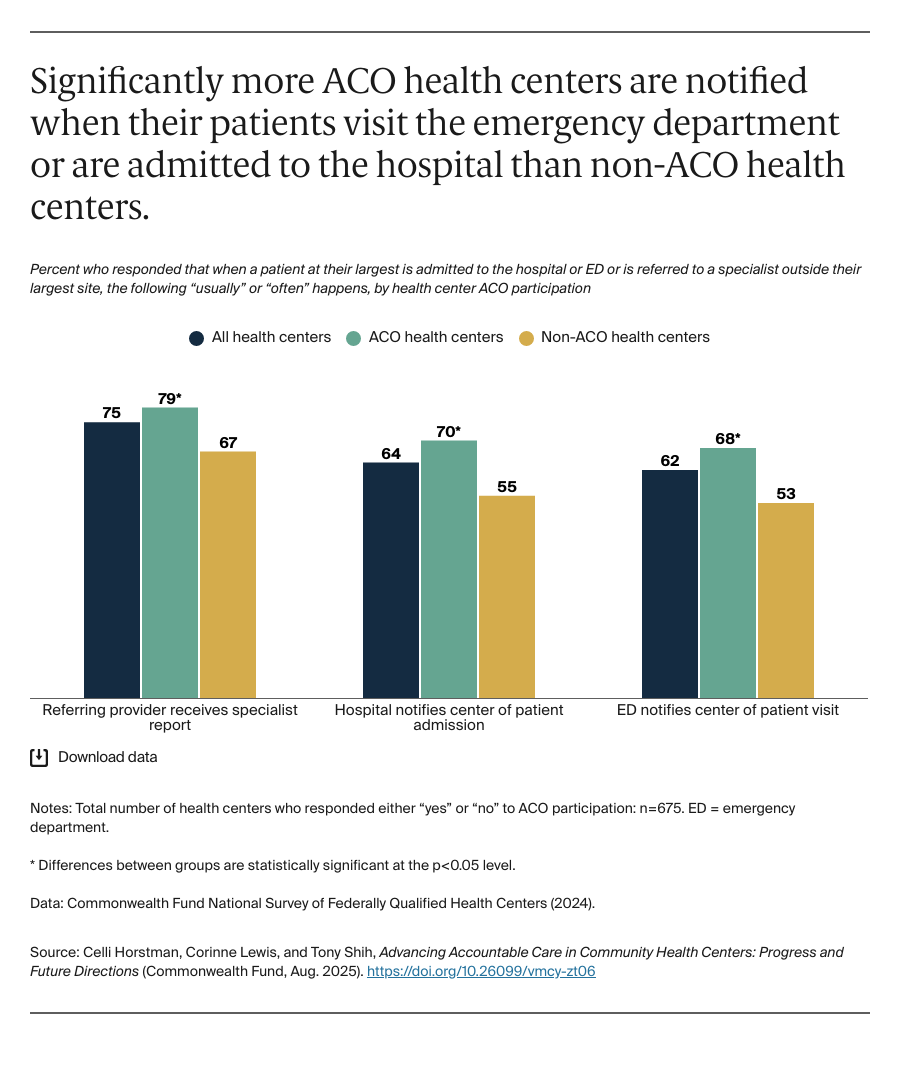

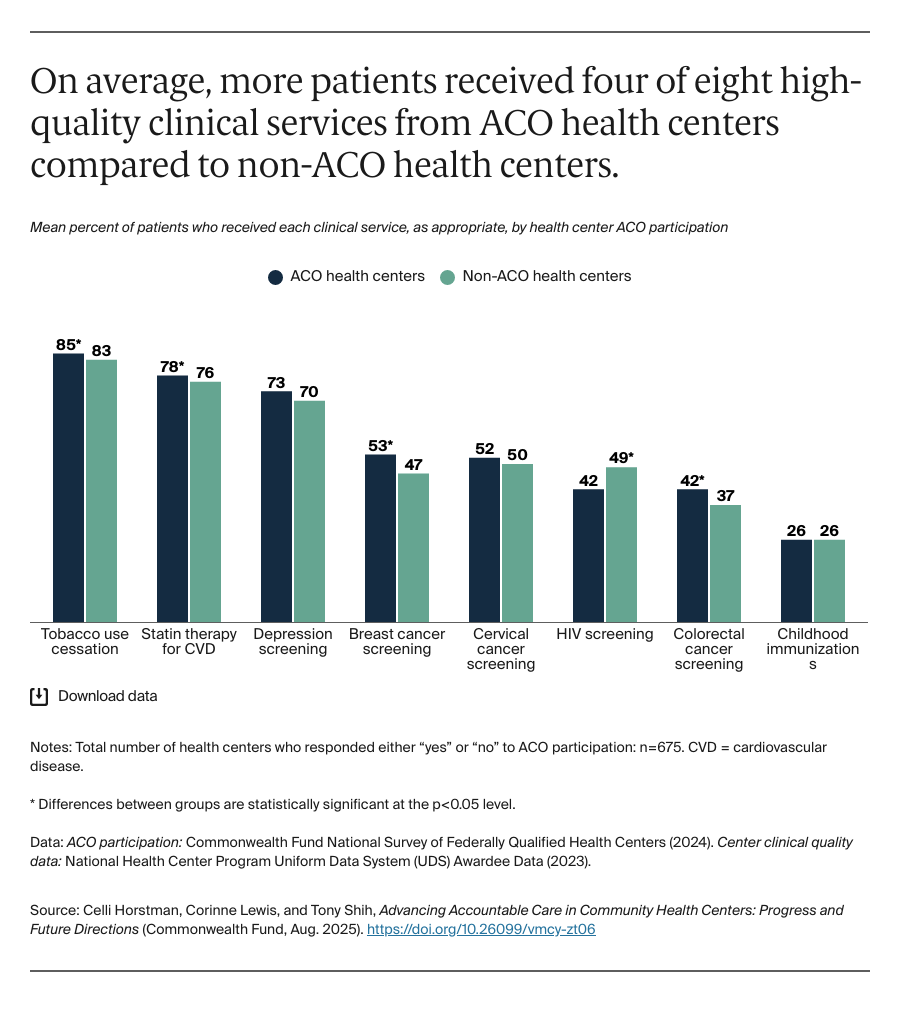

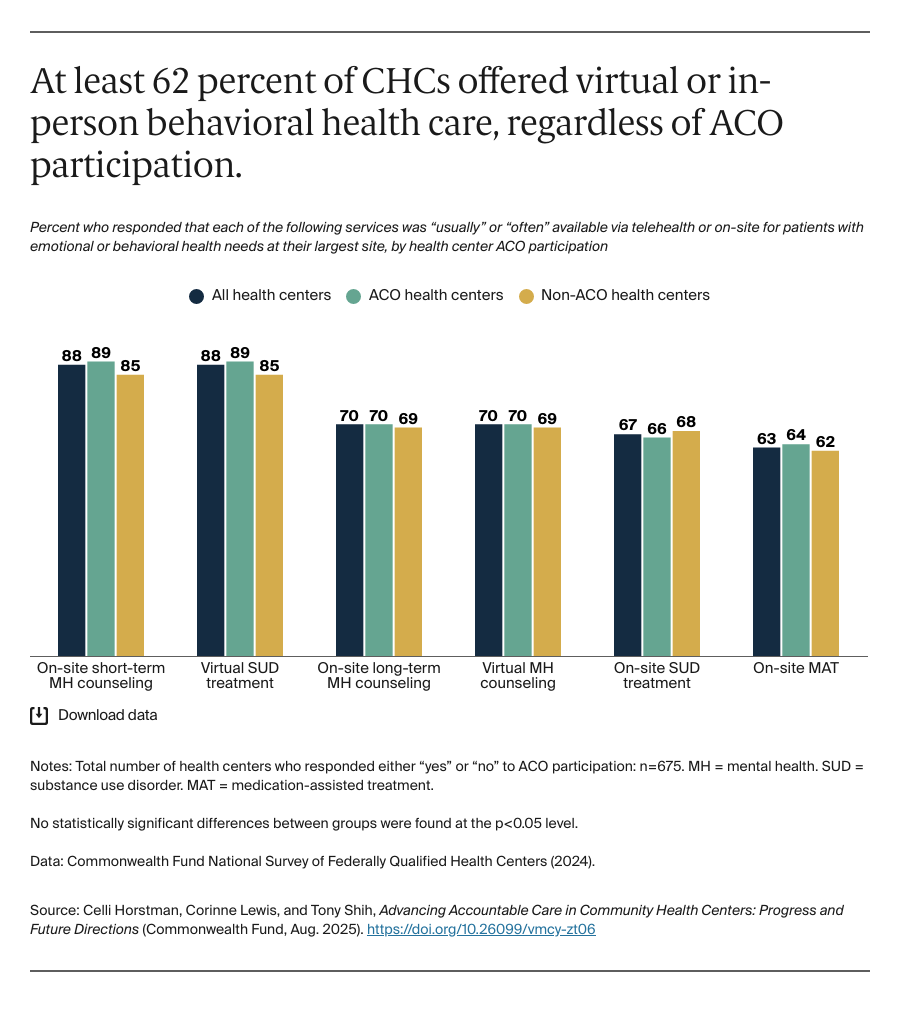

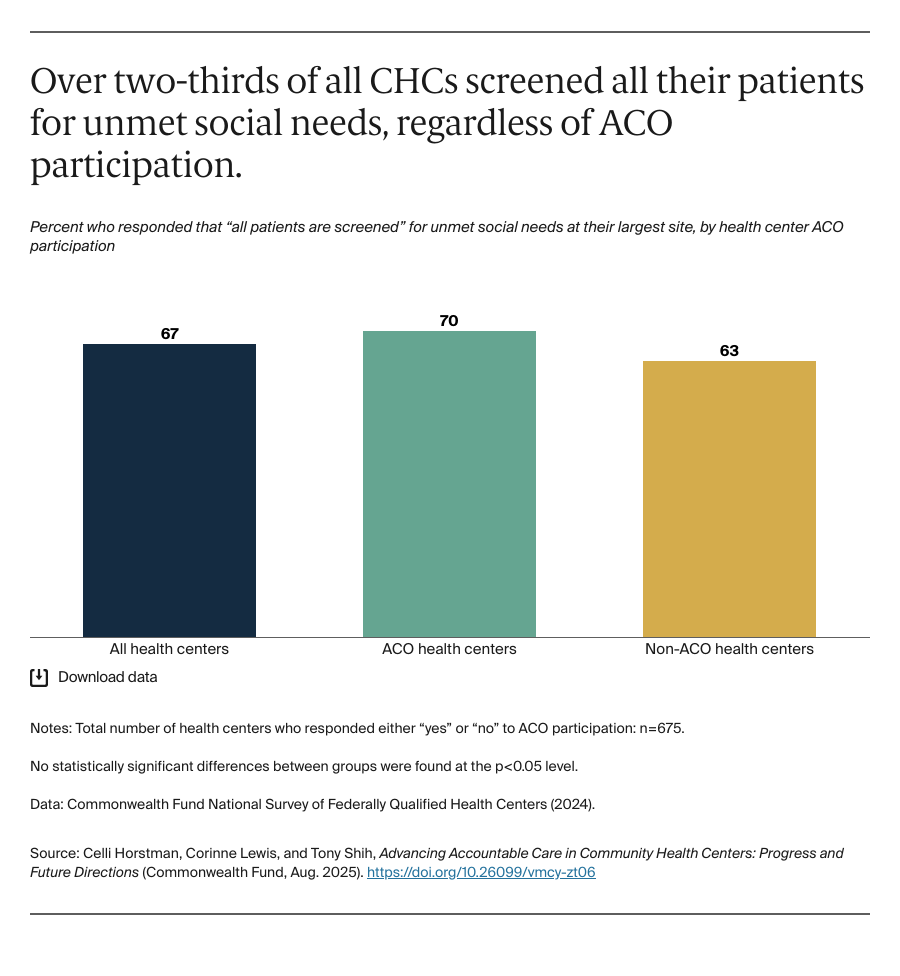

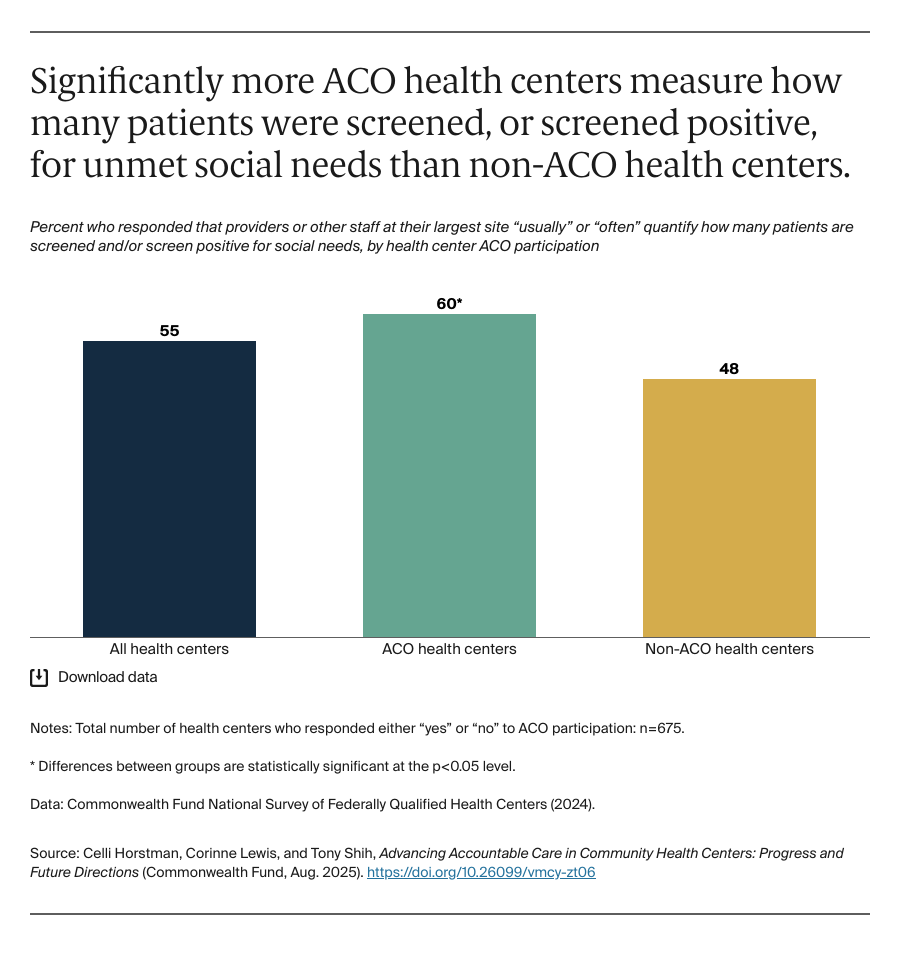

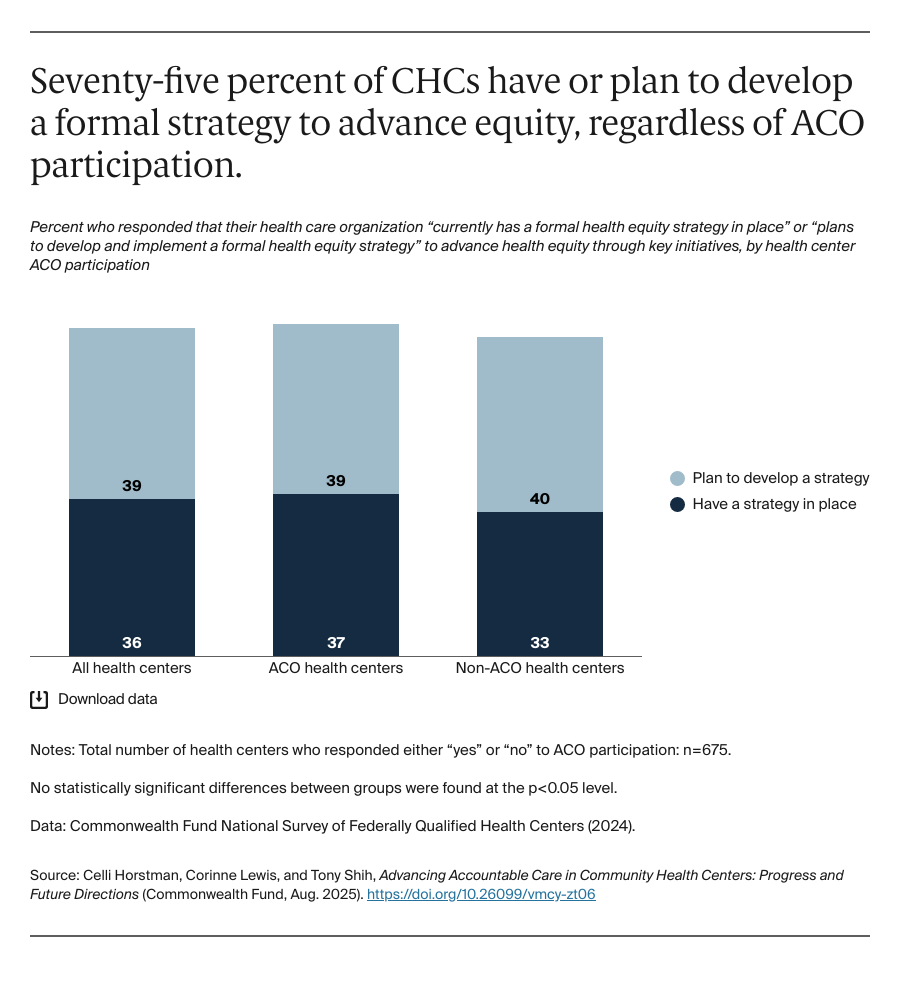

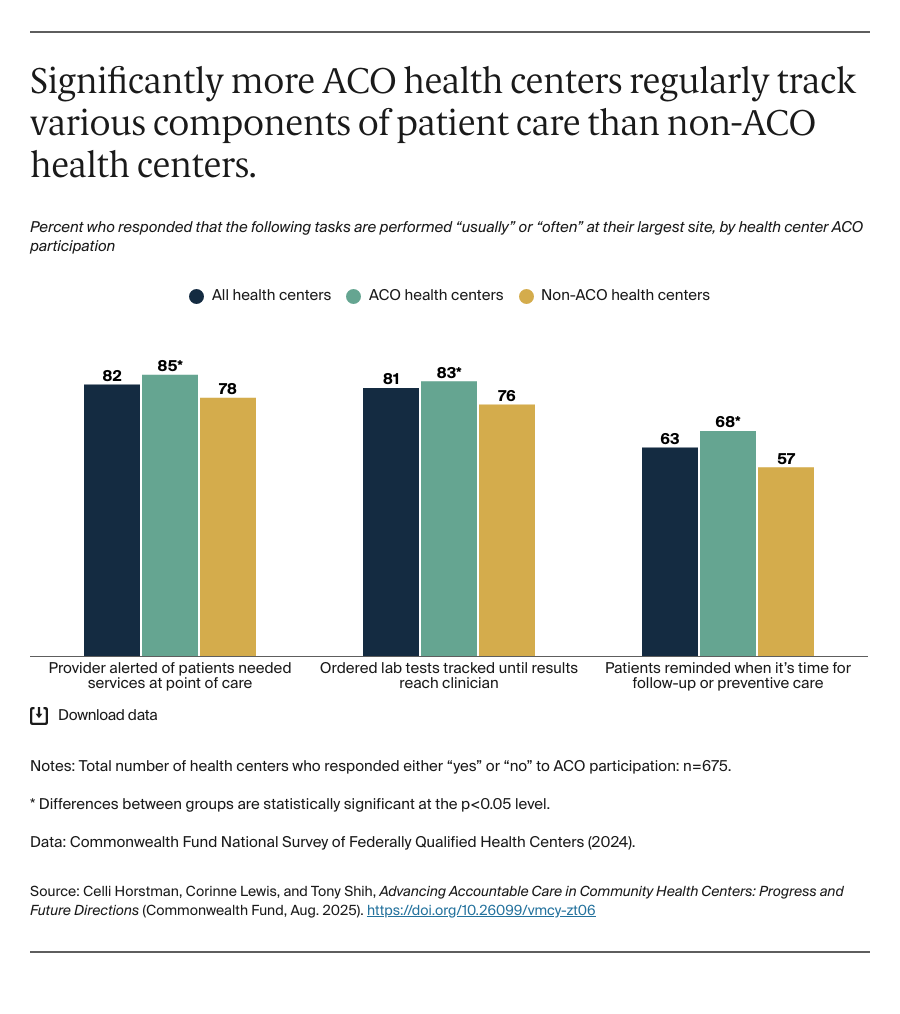

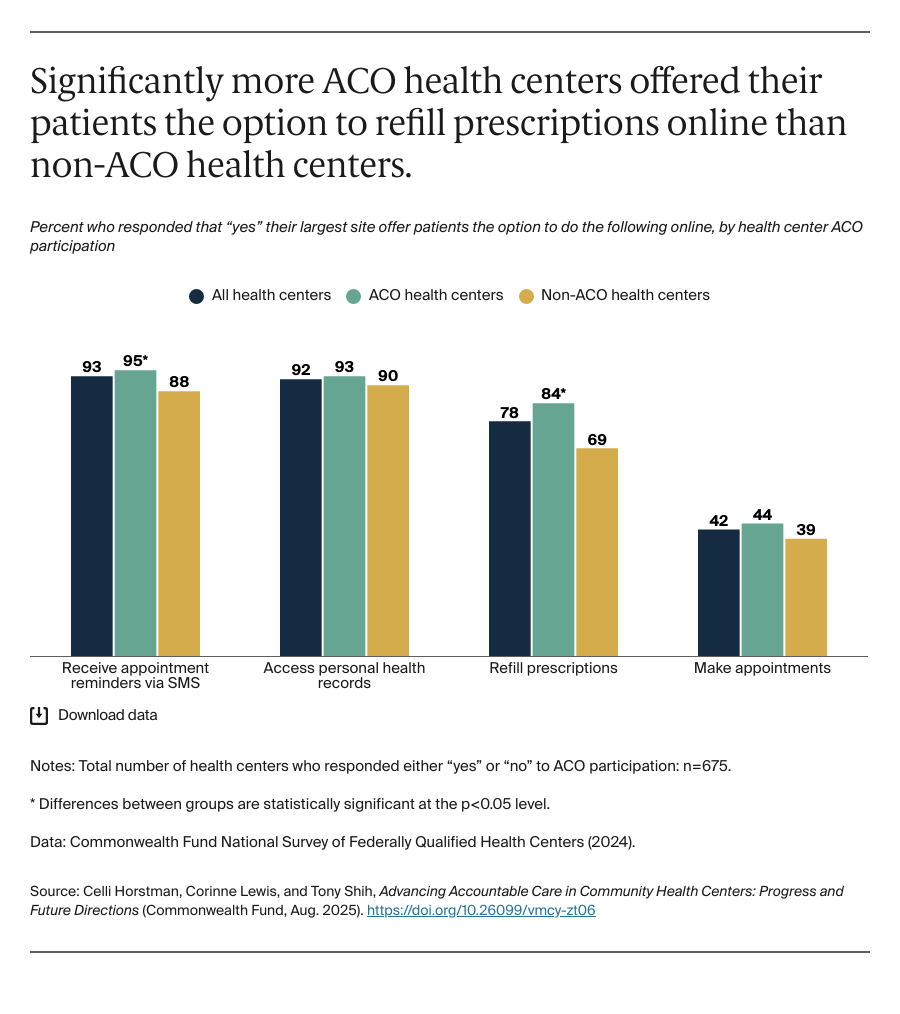

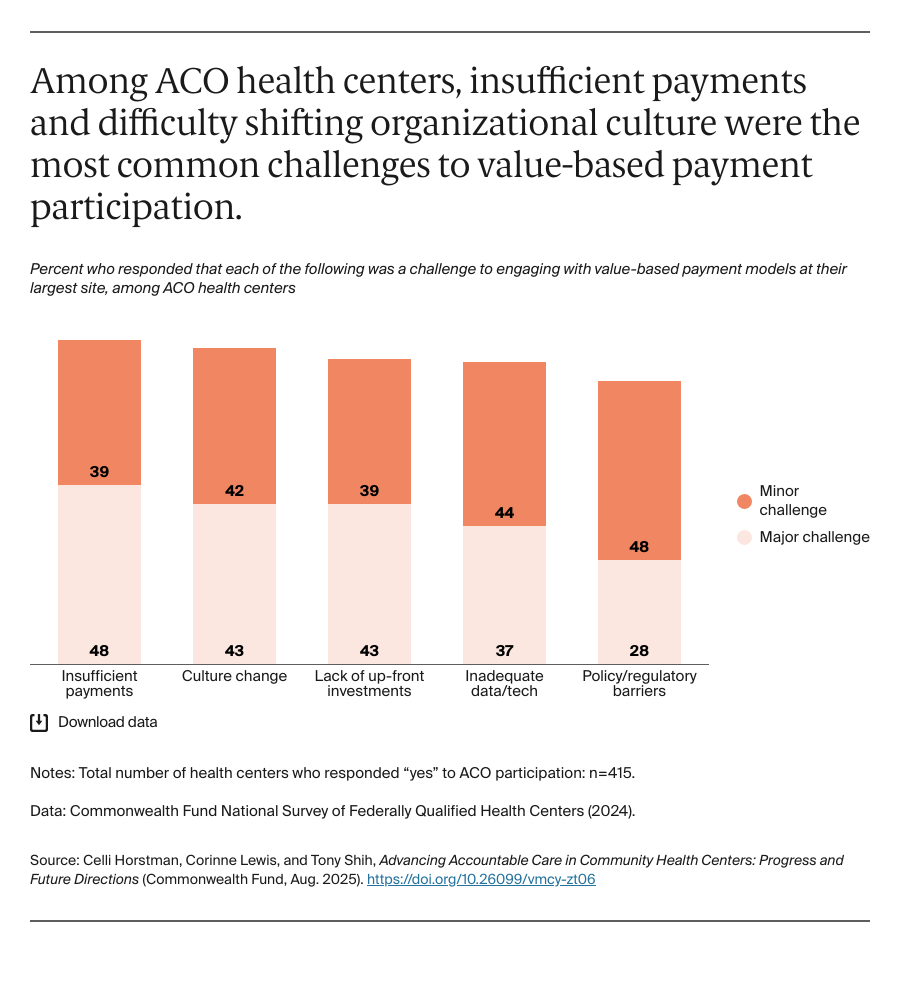

To improve the quality of care and lower the cost, ACO participants coordinate care with other providers; track, report, and work to improve care quality measures; identify and address inequities; offer more comprehensive services such as care management to reduce costly complications; develop data and technology infrastructure; and adopt new payment models.5 Undertaking these activities can be more difficult for CHCs, however. These health centers tend to operate on thin financial margins and with fewer resources, as they are funded largely through a combination of low reimbursements and stagnant federal grants.6 At the same time, CHCs are often uniquely positioned to succeed in these areas, some of which have long been among the criteria for federal funding and regulatory approval.

In this brief, we explore CHC participation in ACOs across key areas such as care coordination, quality and comprehensiveness of services, efforts to advance health equity, data and infrastructure, and payment reform to assess strengths and potential areas for improvement. In addition, we identify how ACO model design could better accommodate the unique characteristics of CHCs. We draw from the 2024 Commonwealth Fund National Survey of Federally Qualified Health Centers, specifically data from the 675 CHCs that responded to the survey’s question regarding ACO participation at their largest site, as well as national data on federally qualified health centers (see “How We Conducted This Study” for more detail).7