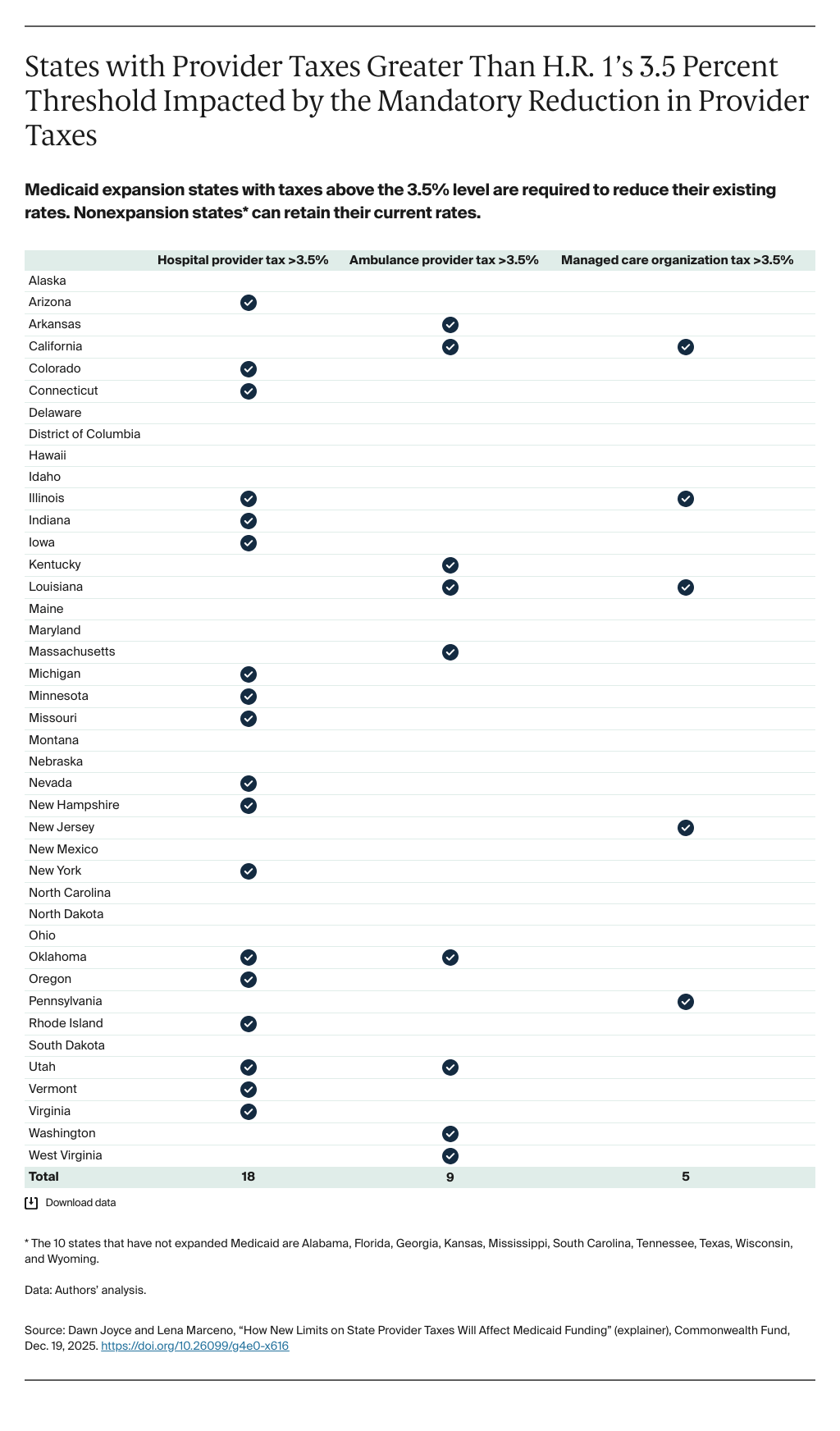

Congress authorized more than $900 billion in Medicaid cuts, the largest in the program’s 60-year history, when it passed its budget reconciliation bill in July 2025. The tax and spending law, known as H.R. 1 or the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, significantly limits states’ ability to impose or raise taxes on health care providers, one of the primary tools that states have at their disposal to fund their portion of Medicaid financing. With this change, states will face greater challenges raising money to pay for their residents’ Medicaid coverage. As explained below, this change in policy is likely to lead to coverage losses, lower provider payment rates, diminished access to care for Medicaid enrollees, and a weakened health coverage safety net for some of the nation’s most economically and socially vulnerable individuals.

How do states currently use provider taxes to fund Medicaid?

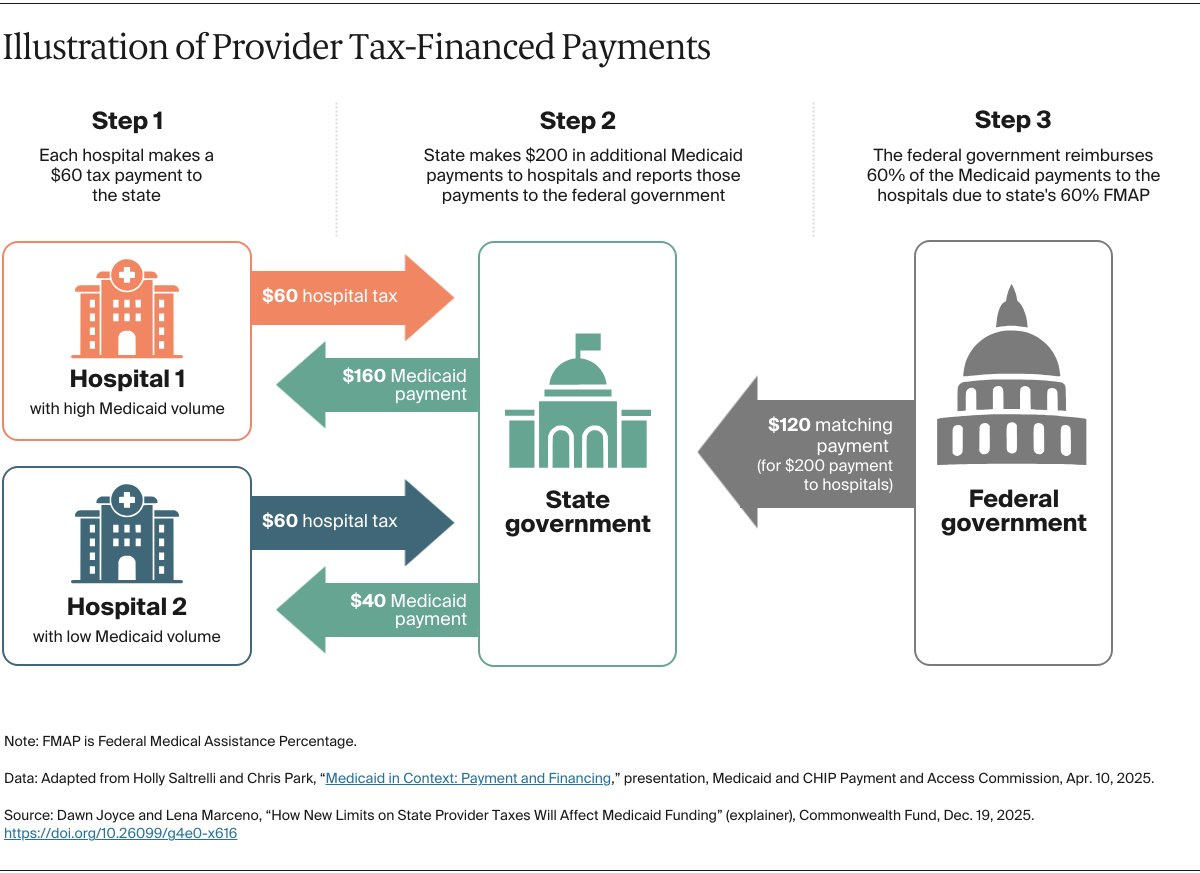

Medicaid, the public coverage program for people with low income and individuals with disabilities, is jointly funded by the federal and state governments. To raise funding for their share of program costs, states levy taxes on providers like hospitals, ambulance companies, nursing homes, and managed care organizations. States then use that revenue to “draw down,” or claim their share of, federal matching dollars. The specific level of federal funding a state draws down is based on the state’s Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) rate, which ranges from 50 percent to 83 percent, with an enhanced FMAP of 90 percent for the Medicaid expansion group.

This provider tax revenue funds approximately $37 billion of the annual state share of Medicaid funding, or an average of 18 percent of that share nationwide. States have used these funds since 1980 to finance an array of Medicaid services, such as maternal health care, services for patients with disabilities, and children’s behavioral health services.

What did provider tax requirements look like before H.R. 1?

For a state to receive matched federal dollars for Medicaid, its provider tax must be the same for all providers in a class, such as all hospitals. States also cannot guarantee that providers will receive all or most of their payment back through direct payments or indirect arrangements designed to cover the cost of the tax (the “hold harmless” provision).

Before H.R. 1, states were allowed to draw down a federal match as long as their provider taxes did not exceed 6 percent of a provider’s net patient revenue — known as the “safe harbor” threshold. The diagram below illustrates how provider taxes work.