Medicaid serves as a lifeline for nearly 80 million people nationwide, yet the payments that providers receive for treating Medicaid patients often fall below the cost of delivering care. Because of chronic underfunding, many providers who treat large shares of Medicaid patients struggle to survive, with limited ability to invest in innovations to strengthen care quality and improve efficiency.

Historically, states that contract with health insurance plans to deliver services to Medicaid beneficiaries have been limited in their ability to direct plans on how they pay providers. Over the past decade, subject to federal guardrails, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has permitted states to establish state-directed payments (SDPs) that direct Medicaid managed care plans to enhance rates (up to average commercial rates) for hospitals and other providers; support systemwide, value-based payment reforms; and enhance care quality. In Arizona, for example, SDPs for hospitals are tied to efforts to reduce unnecessary hospital readmissions. As with other Medicaid spending, states and the federal government share in the cost of SDPs.

Over the years, SDPs have become a foundational tool to boost low Medicaid payments, and improve access and quality, accounting for $110.2 billion in annual Medicaid spending. However, the growth in the size of SDPs and number of states using them has attracted considerable attention, making SDPs a target for cuts in House and Senate reconciliation bills. Often lost in this debate is the critical role SDPs play for safety-net providers, including children’s hospitals, which serve many people enrolled in Medicaid, and rural providers.

State-Directed Payments Are at Risk

The budget reconciliation bill passed by the House in May would allow existing SDPs to stay in place but would freeze the annual amounts paid and limit the level of all new SDPs to 100 percent of Medicare rates (or 110% of Medicare rates for states that haven’t expanded Medicaid), a payment level that is often a half or even a third of average commercial rates (ACR). The Senate, which recently passed its version of the reconciliation bill, would deepen the cuts by unraveling the freeze on current SDPs. The Senate version would reduce SDPs already in place by 10 percentage points until they reach 100 percent or 110 percent of Medicare rates, for Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states, respectively. According to the Congressional Budget Office estimates, the Senate provisions would reduce SDP payments nationwide by $149 billion over 10 years. The final form of congressionally mandated SDP policy changes is yet to be seen.

While this policy would affect providers across the nation, it hits hospitals, pediatric providers, and rural providers particularly hard. These providers serve a relatively high number of Medicaid patients, and many have relatively little commercial revenue to rely on. Under the proposals, states and providers will face a twofold problem: the value of existing SDPs will erode quickly, with the gap between payments and costs growing each year, and states that have not yet increased payments to the ACR (or any rate above Medicare) would be prevented from doing so.

Impact of State-Directed Payment Cuts

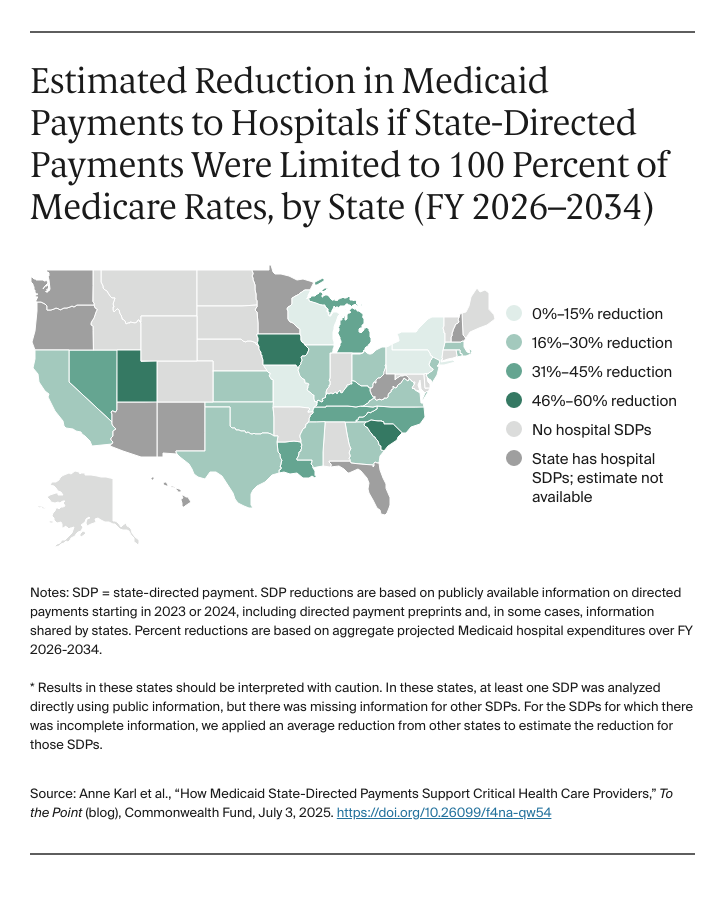

We analyzed the amount Medicaid payments to hospitals would be reduced if the 100 percent of Medicare limit were applied across any state with hospital SDPs. In 19 of the 25 states for which data are publicly available, total Medicaid payments to hospitals would drop by at least 20 percent.