Abstract

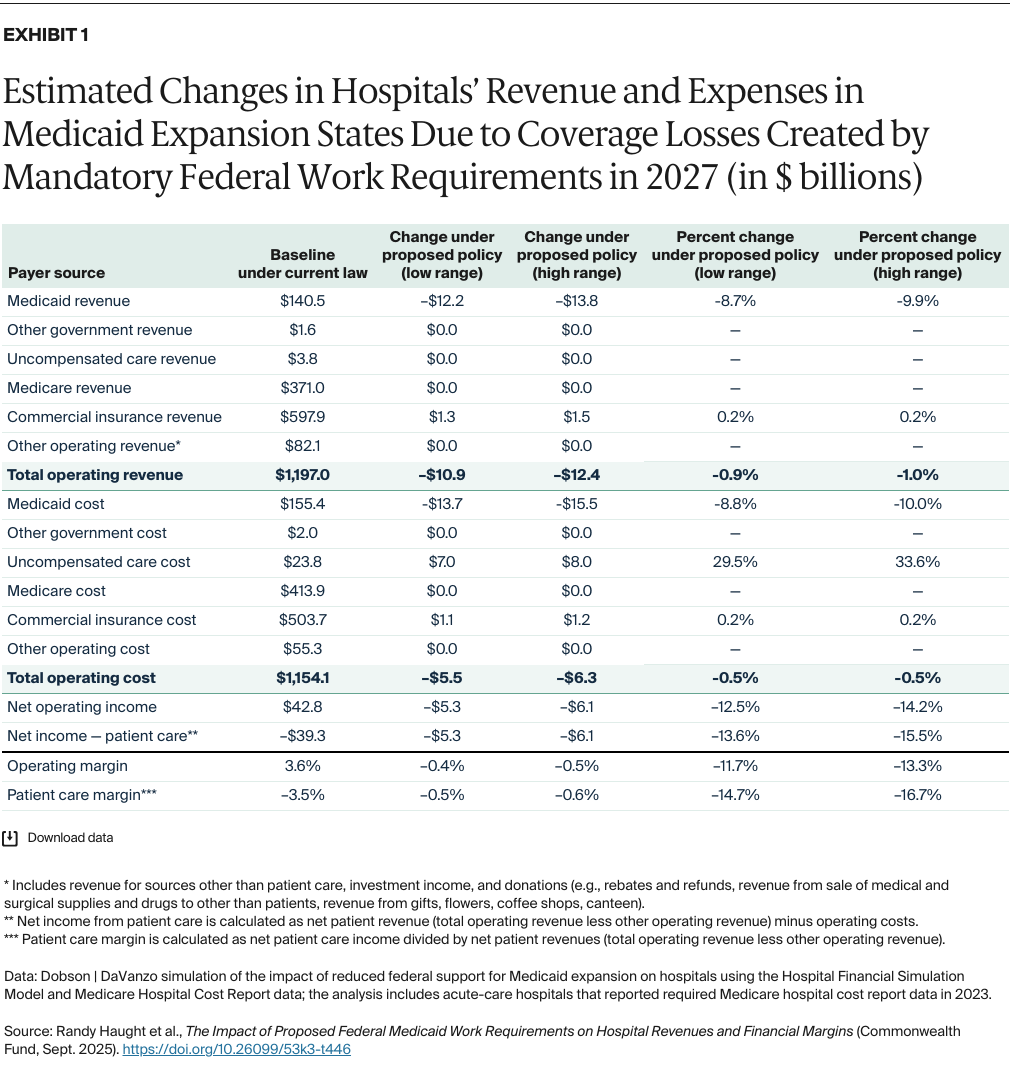

- Issue: Analyses of mandatory federal work requirements for Americans covered by the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid eligibility expansion have focused on potential coverage losses, overlooking the financial impact on health care providers.

- Goal: To assess the financial impact of the work requirement policy on hospitals in affected states.

- Methods: We used Urban Institute estimates of coverage losses to project the financial impact on acute-care hospitals.

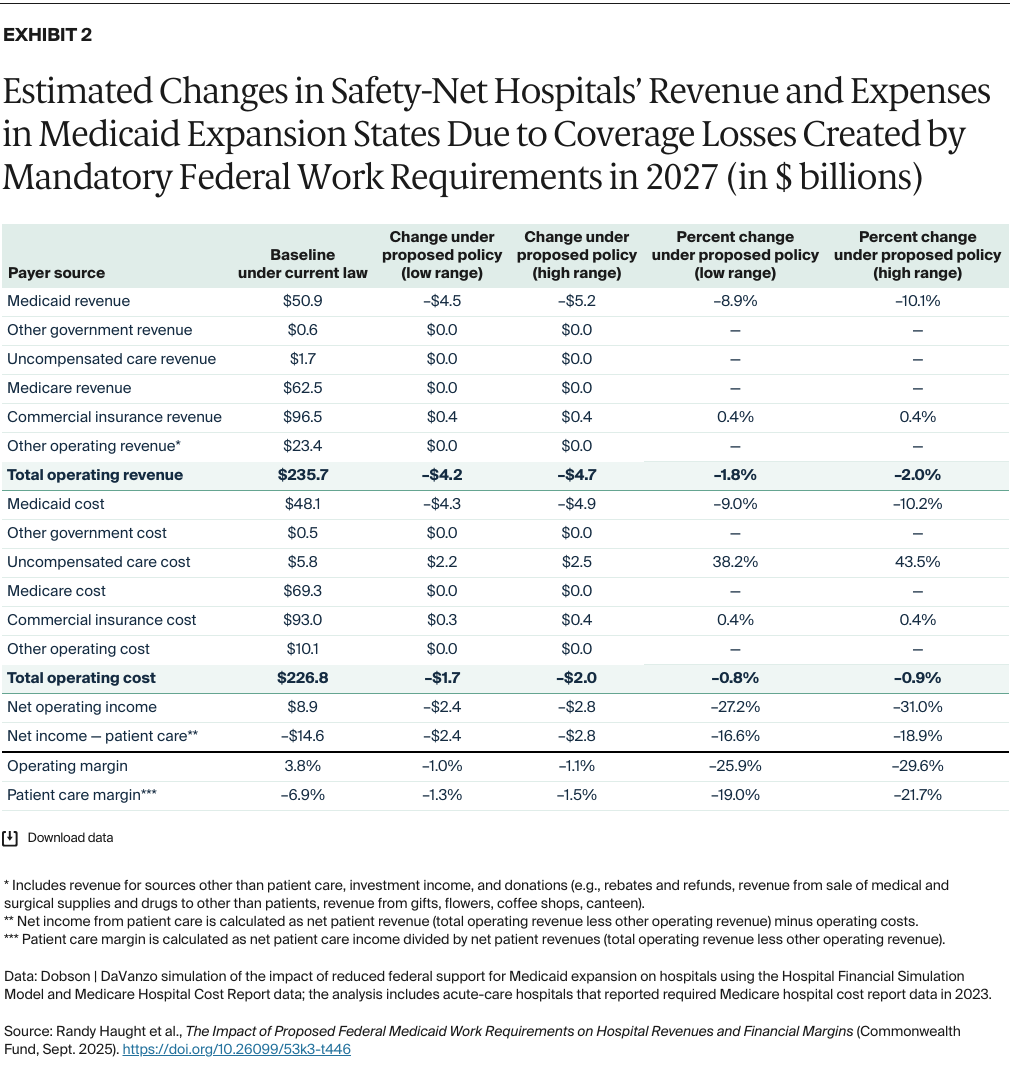

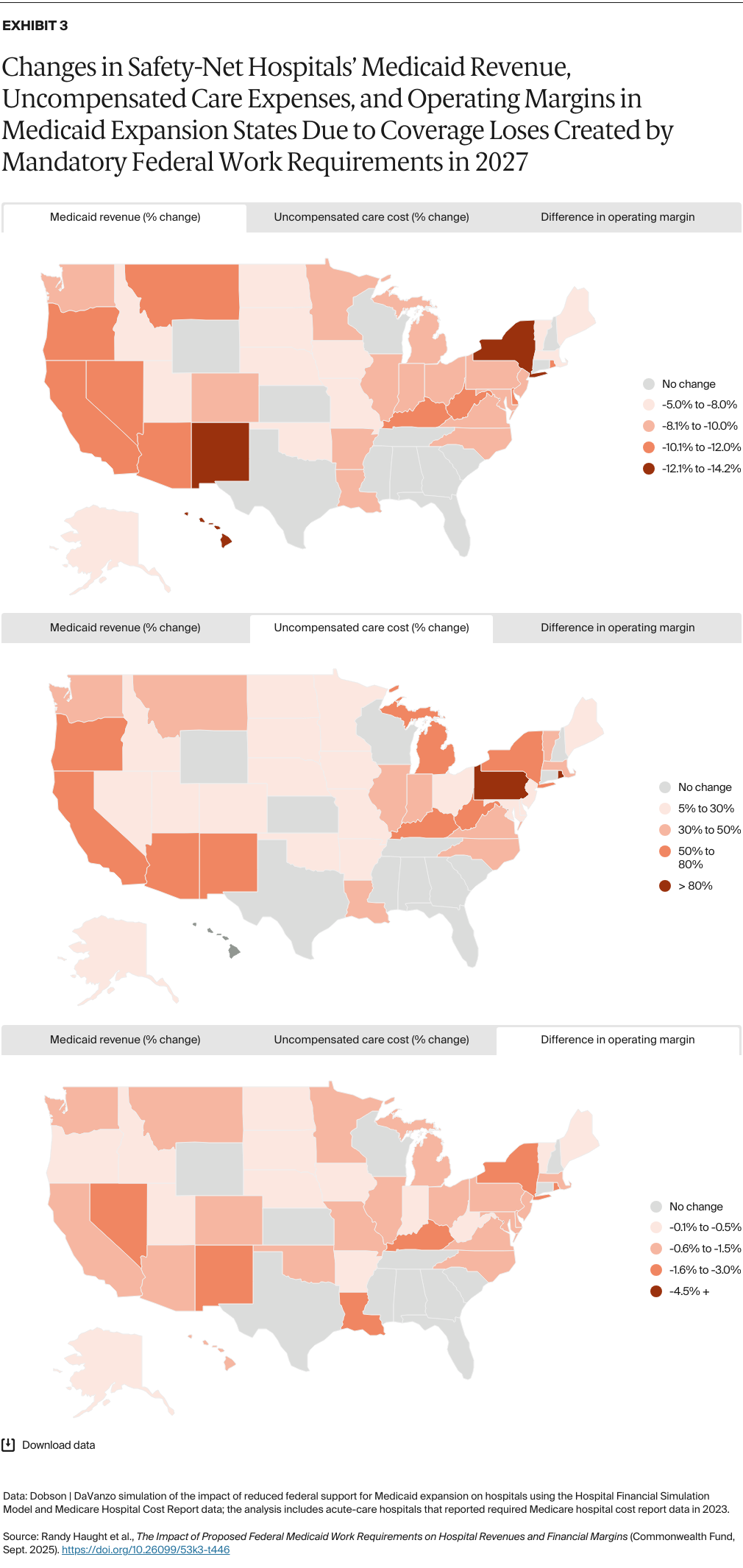

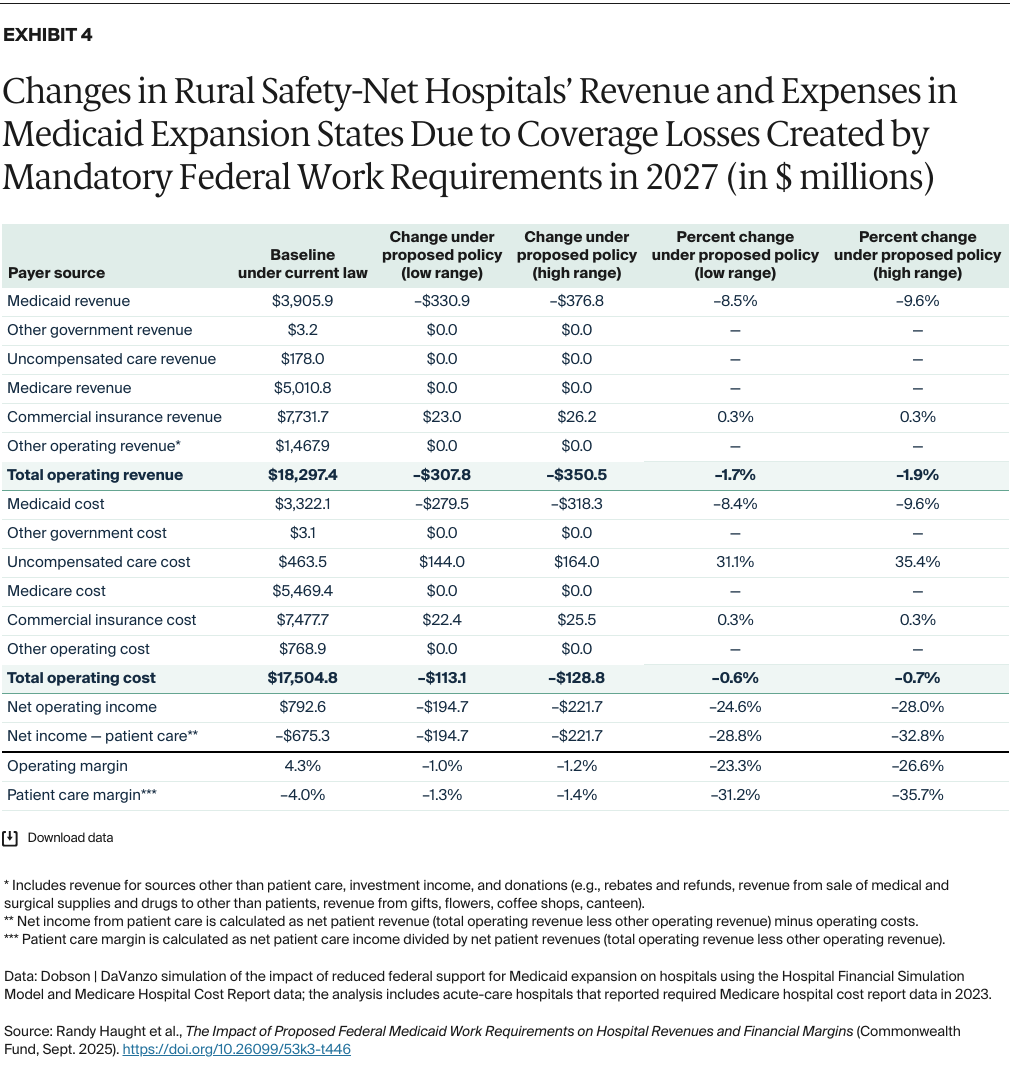

- Key Findings and Conclusion: Hospitals in Medicaid expansion states could see operating margins reduced by an average of 11.7 percent to 13.3 percent. Safety-net hospitals could be disproportionately impacted: their operating margins could fall by an average of 25.9 percent to 29.6 percent, and even more in certain states and in rural areas. Both Medicaid enrollees and the broader communities that hospitals serve would likely be affected, as lower revenues and increased uncompensated care costs could force hospitals to reduce staff or eliminate services.

Background

Congress recently passed unprecedented cuts to federal Medicaid spending that will not only impact beneficiaries but the entire safety-net system that serves a wide array of patients and families. To achieve a large portion of these cuts, lawmakers adopted mandatory federal work requirements for people who qualified for Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) expansion of eligibility. Under this policy, enrollees ages 19 to 64 must engage in at least 80 hours per month of community engagement activities (such as work, volunteering, or enrollment in an educational program) and must verify these activities twice a year to retain coverage. The law exempts caregivers of dependent children under age 14, people with disabilities, people who are pregnant, and several other groups.1

Forty states, along with the District of Columbia, have expanded Medicaid eligibility to nonelderly adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) — more than 16 million people in 2024.2 In these states, Medicaid beneficiaries could lose health insurance if they cannot find work, are unable to document the required number of hours they work, or cannot document an exemption. While the vast majority of Medicaid beneficiaries subject to the requirements either work or qualify for an exemption, millions could lose coverage because of difficulties they experience in navigating complex work-reporting and verification systems or the work-requirement exemption process. Others who could lose their Medicaid are people who have been laid off or are temporarily unemployed.

While the work requirement policy could generate federal and state savings by reducing the number of people that receive Medicaid insurance, it could leave many uninsured. This would lead to lower revenues and higher uncompensated care costs for hospitals.

Alongside the potential loss of coverage for Medicaid beneficiaries is the work requirement policy’s impact on hospitals — a subject that has received less attention. Coverage losses will affect hospitals by reducing their revenue and increasing uncompensated care costs. These adverse outcomes will affect not only Medicaid patients but the broader community as well, since lower revenues and increased uncompensated care could force many hospitals to reduce staff and payroll or eliminate important clinical services used by all patients.3

Based on the impact that Arkansas and New Hampshire’s state work requirement programs had prior to their halt in 2019, the Urban Institute has estimated that about 5.5 million to 6.3 million people across all Medicaid expansion states would lose access to coverage if such a policy were fully implemented in 2026.4 Although the Urban Institute report did not attempt to estimate the number of people losing Medicaid coverage who would become uninsured, our estimates show that 5.1 million to 5.8 million people would become uninsured and that 400,000 to 500,000 individuals would either enroll in employer-sponsored health coverage or purchase nongroup health insurance (see “How We Conducted This Study” for details). In comparison, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that 5.2 million people would lose Medicaid coverage and 4.8 million would become uninsured by 2034.5 The Urban Institute study assumed that Medicaid agencies would rely on existing state databases to automatically determine whether enrollees are meeting work requirements or are exempt from the policy, using data-matching processes similar to those that Arkansas and New Hampshire used previously. The study’s estimates also assumed that noncompliance rates for people not automatically exempted from the reporting requirement are consistent with the noncompliance rates observed in Arkansas (with a low-range estimate of 72%) and New Hampshire (with a high-range estimate of 82%).

In this brief, we examine the potential financial impact of federal mandatory work requirements on hospitals once the new policy is implemented for Medicaid expansion enrollees in 40 states and the District of Columbia. Our analysis provides high- and low-range estimates of the impact of Medicaid coverage loss on revenues, uncompensated care costs, and financial margins for hospitals in the affected states. For modeling purposes, we assume the policy is fully implemented in all expansion states in 2027. We present impact estimates by state and focus on two specific subgroups of hospitals: safety-net hospitals and rural hospitals (see “How We Conducted This Study” for details).

How Medicaid Coverage Losses Impact Hospital Finances

Reductions in Medicaid coverage will decrease Medicaid payments and increase uncompensated care costs, resulting in lower hospital operating margins. Exhibit 1 shows the projected baseline revenues and expenses by payer source under current laws for 2,958 general acute-care hospitals in the 40 expansion states and the District of Columbia, compared to projections if the proposed work requirement policy were to be fully implemented.