What are the controversies surrounding the 340B program?

The 340B program has become controversial for several reasons:

Transparency and oversight. The program lacks transparency in many areas, including the actual 340B prices and whether manufacturers are providing the required discounts. It’s also unclear how much revenue covered entities receive from 340B drugs and how they use that revenue. Over the years, Congress has granted HRSA regulatory authority to conduct limited oversight, including auditing covered entities and manufacturers. HRSA also established an administrative dispute resolution process to resolve claims by covered entities that they have been overcharged, as well as claims by manufacturers that they provided duplicate discounts by supplying a drug at the 340B price while also paying a Medicaid rebate. Regardless of whether the 340B program is overseen by HRSA or CMS, these issues are the same.

Duplicate discounts. The longest-standing issue in the 340B program is ensuring that drugs sold at the 340B price are not subject to other statutory discounts in federal health programs, such as Medicaid’s Drug Rebate Program. For example, if a drug were sold to a covered entity at the 340B price and a state Medicaid program were to collect a rebate from the manufacturer for that medication, this would be a “duplicate discount” — something that’s prohibited by law. A similar provision exists for Medicare drugs under the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program.

However, tracking whether a duplicate discount has occurred is complicated, because there is a lack of transparency and coordination among covered entities, contract pharmacies, Medicare and Medicaid, and manufacturers. One analysis suggests that 3 percent to 5 percent of 340B drugs and Medicaid-purchased drugs receive duplicate discounts. HRSA recently announced a voluntary pilot program to test such a rebate model with manufacturers.

Patient definition. Because Congress did not specifically define “patient” in the statute, HRSA established a patient definition through guidance. However, this has created inconsistencies. For example, while community clinics that participate in the program can purchase 340B drugs only for patients who receive health care services within the scope of a federal grant, hospitals do not have this same requirement. As a result, manufacturers and some academic researchers have raised concerns that certain hospitals could take advantage of the program — in particular, by shifting care from underserved areas to wealthier communities in a bid to raise revenue.

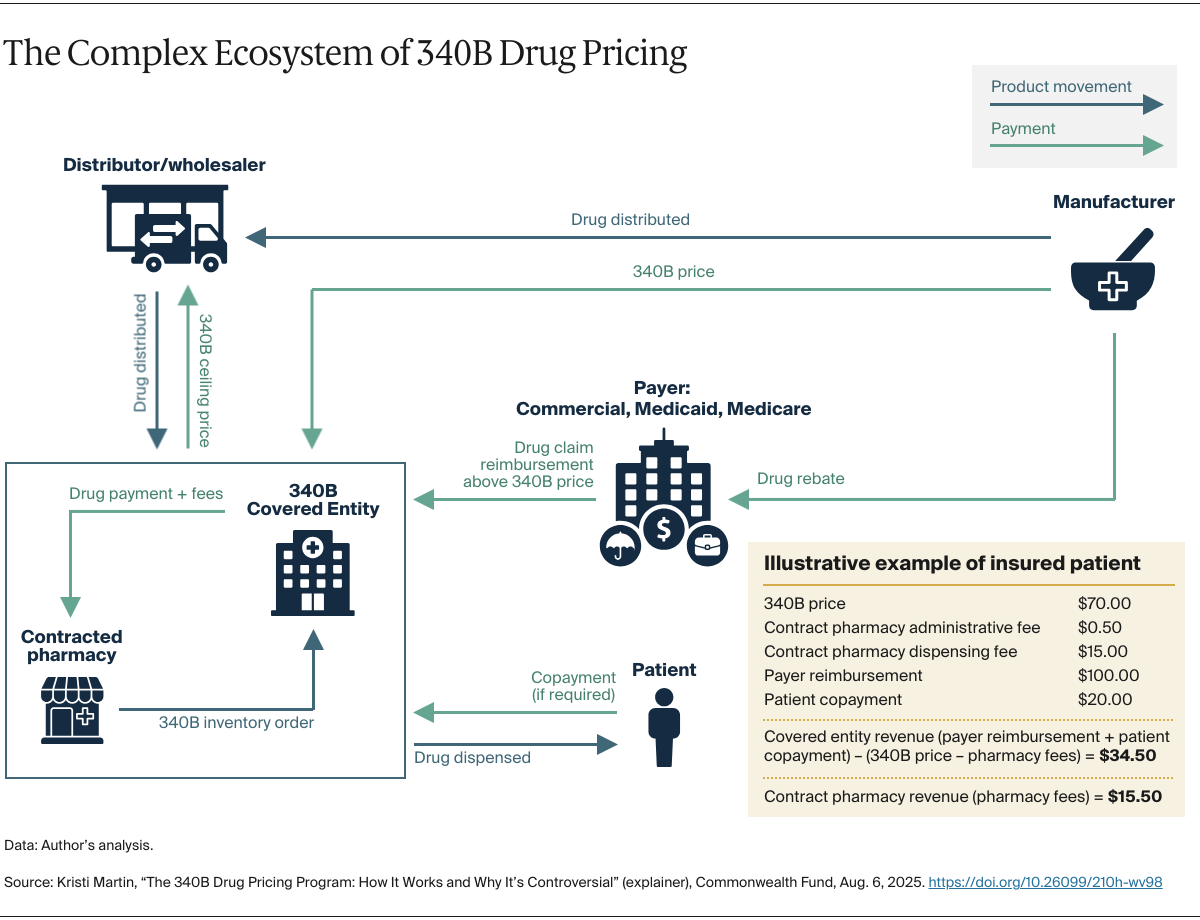

Who reaps the “savings.” Congress specified that 340B revenue is intended for covered entities. There are questions, however, about how this revenue is being used. While some hospitals and clinics use it to expand services for their low-income patients, they are not required to pass along the 340B discounted price or offer reduced cost sharing for drugs. As a result, there are cases where covered entities do not provide discounts on 340B drugs to patients with low income or no insurance.

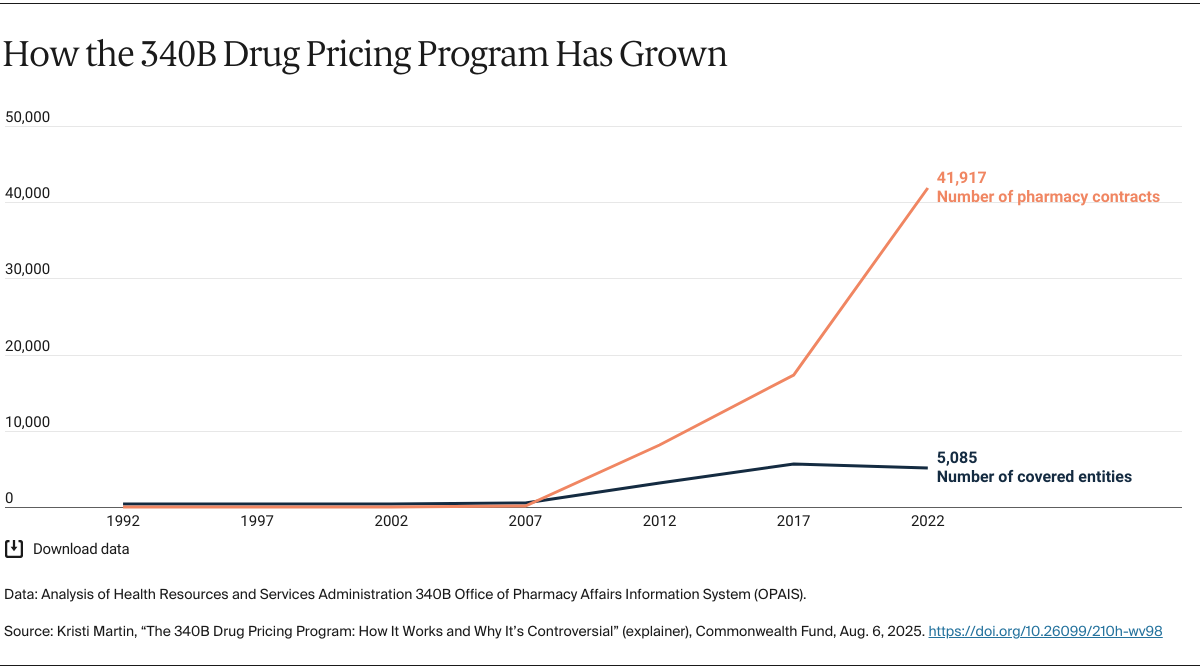

Program growth. The number of hospitals eligible to participate in the program increased dramatically because of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which expanded the types of hospitals eligible (such as critical access hospitals and rural treatment centers). The ACA also expanded Medicaid, which resulted in more hospitals qualifying as disproportionate share hospitals. Originally, there were 1,000 covered entities, including their registered sites in the program in 1992. Today there are more than 53,000 sites, representing more than 40 percent of the hospitals in the country.

While the use of contract pharmacies has been permitted since the early days of the program, their involvement has grown since 2010. That year, HRSA amended rules that permitted a covered entity to use an unlimited number of contract pharmacies rather than a single pharmacy. Since then, the number of contract pharmacies, predominantly for-profit companies that retain revenue generated from the program, increased from roughly 1,000 in 2010 to more than 25,000 in 2022, with many having 10 or more contracts. With some contract pharmacies charging fees ranging from $15 to more than $1,700 per drug, these pharmacies’ expanded involvement in 340B has drawn scrutiny, including recent litigation.

What reforms have been proposed to address concerns about the 340B program?

Policymakers at the federal and state level have considered a number of reforms, many of which have bipartisan support, to improve oversight and implementation of the 340B program:

Enhance oversight. A common theme with the controversies surrounding the program is HRSA’s lack of regulatory authority. Congress could consider providing HRSA rulemaking authority to set clear, enforceable standards for participation in all aspects of the 340B program.

Increase transparency. One option is allowing a federal and/or state agency to collect data from covered entities annually to quantify the net revenue generated from the program and understand how covered entities use it. Similarly, providing additional resources to HRSA could help ensure more covered entities and manufacturers follow the program requirements. In fiscal year 2024, HRSA performed 144 audits of covered entities and five audits of manufacturers.

Address duplicate discounts. Some states have “carved in” 340B, meaning their Medicaid programs allow a covered entity to purchase a drug at 340B pricing to dispense to a Medicaid patient, but the states don’t claim a Medicaid rebate from the manufacturer. Other states have “carved out” 340B, meaning their Medicaid programs prohibit a covered entity from using 340B pricing for a Medicaid patient, and the states claim a Medicaid rebate from the manufacturer.

Manufacturers are pushing to apply the retrospective rebate model for generating the 340B discount. Policymakers could specify what models are acceptable to avoid duplicate discounts.

Clarify definitions and provisions in the existing 340B law. First, policymakers could clarify the definition of “patient” for hospitals, similar to how the definition applies to community clinics. Second, policymakers could better define the role contract pharmacies should play in the 340B program. Finally, policymakers could consider clarifying how the revenue generated from 340B drugs should be used by covered entities (such as requiring the use of a sliding scale for patient cost sharing for a 340B drug or specifying that a minimal amount of 340B revenue is used for charity care).

By implementing such reforms, policymakers could reduce some of the controversy surrounding the 340B program, increase transparency, and help promote its original intent to improve patient access to affordable care.