Medicare beneficiaries can receive their benefits either through private plans, known as Medicare Advantage (MA) plans, or traditional Medicare. MA plans now cover more than half of all beneficiaries, and their growth has come with heightened scrutiny over the appropriateness of taxpayer-funded payments they receive from the federal government.

One aspect affecting payments to MA plans that has come under review is risk adjustment. Risk adjustment is a method to calculate payments based on patients’ expected health care needs. This explainer describes how risk adjustment works and how federal policymakers might consider reforming it.

What is risk adjustment?

Unlike traditional Medicare that’s primarily paid through a fee-for-service system after care is given, MA plans receive prospective capitated payments, which are lump sum amounts to cover expected future health care services for a patient. If given the same lump sum for each patient, plans have less financial incentive to enroll sicker patients with greater health care needs and expenses.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) first implemented risk adjustment for MA’s precursor program in 1985. The agency has evolved its methods over time to ensure that MA plans were not financially deterred from enrolling sicker people who need more medical care. Risk adjustment does this by modifying payments — up or down — to account for enrollee characteristics and health conditions that are expected to affect future health care costs.

How does risk adjustment in Medicare Advantage currently work?

Using what’s known as the Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCC) model, CMS estimates enrollees’ health care costs for the coming year. In the model, each demographic characteristic or health condition (known as a risk factor) is associated with an expected cost, based on past fee-for-service claims data from patients with traditional Medicare. Diagnoses can influence payment only if they resulted from hospital inpatient stays, hospital outpatient visits, or face-to-face visits with health care professionals.

Each enrollee is assigned a risk score that reflects the sum of their risk factors and their predicted health care costs. Higher risk scores result in higher per-beneficiary payments to plans.

What are the shortcomings of CMS’s current approach?

Incomplete or unrepresentative data. Declining enrollment in traditional Medicare has raised concerns over whether fee-for-service claims data can continue to accurately predict expenses for Medicare Advantage enrollees. Research also finds that MA beneficiaries generally cost less than their risk scores predict, a pattern known as “favorable selection.” In other words, the HCC model overestimates what MA enrollees would cost, leading to higher plan payments for enrollees who don’t always require more care.

In recent years, CMS started using plan-submitted “encounter data” — or data on the actual items and services provided to MA enrollees — to capture patients’ diagnoses for risk adjustment. But regulators and researchers have found issues with the completeness and validity of the data. Audits from the Office of the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) found that 70 percent of diagnosis codes were not supported by medical records.

Encouragement of “overcoding.” MA plans have faced scrutiny for overcoding, or documenting patient conditions with no bearing on actual expenditures, which inflates payments. (“Upcoding,” another tactic some plans use, is a specific kind of overcoding in which patient diagnoses are reported as more severe than they actually are.) The federal government joined lawsuits initiated by whistleblowers against Kaiser Permanente and UnitedHealth Group, alleging that the companies overcoded patients’ records to boost their revenues.

Plans overcode by using chart reviews and health risk assessments to add diagnoses to patients’ records that may not be documented on subsequent visits. Chart reviews and health risk assessments are estimated to account for about half of the more intense coding seen in MA plans.

To reduce the potential for overcoding, the Biden administration removed some conditions from the HCC model that were used inappropriately or unreliably predicted costs. Congress has also required at least a 5.9 percent decrease in risk scores to all plans, known as the coding intensity adjustment. While the HHS Secretary has the authority to require plans to reduce risk scores by more than 5.9 percent, no Secretary ever has.

Some critics argue that an across-the-board adjustment doesn’t do much to encourage competition between MA plans. Because coding practices vary by plan, making the coding intensity adjustment plan-specific could be more effective but poses methodological challenges.

How might CMS reform their approach to risk adjustment for Medicare Advantage plans?

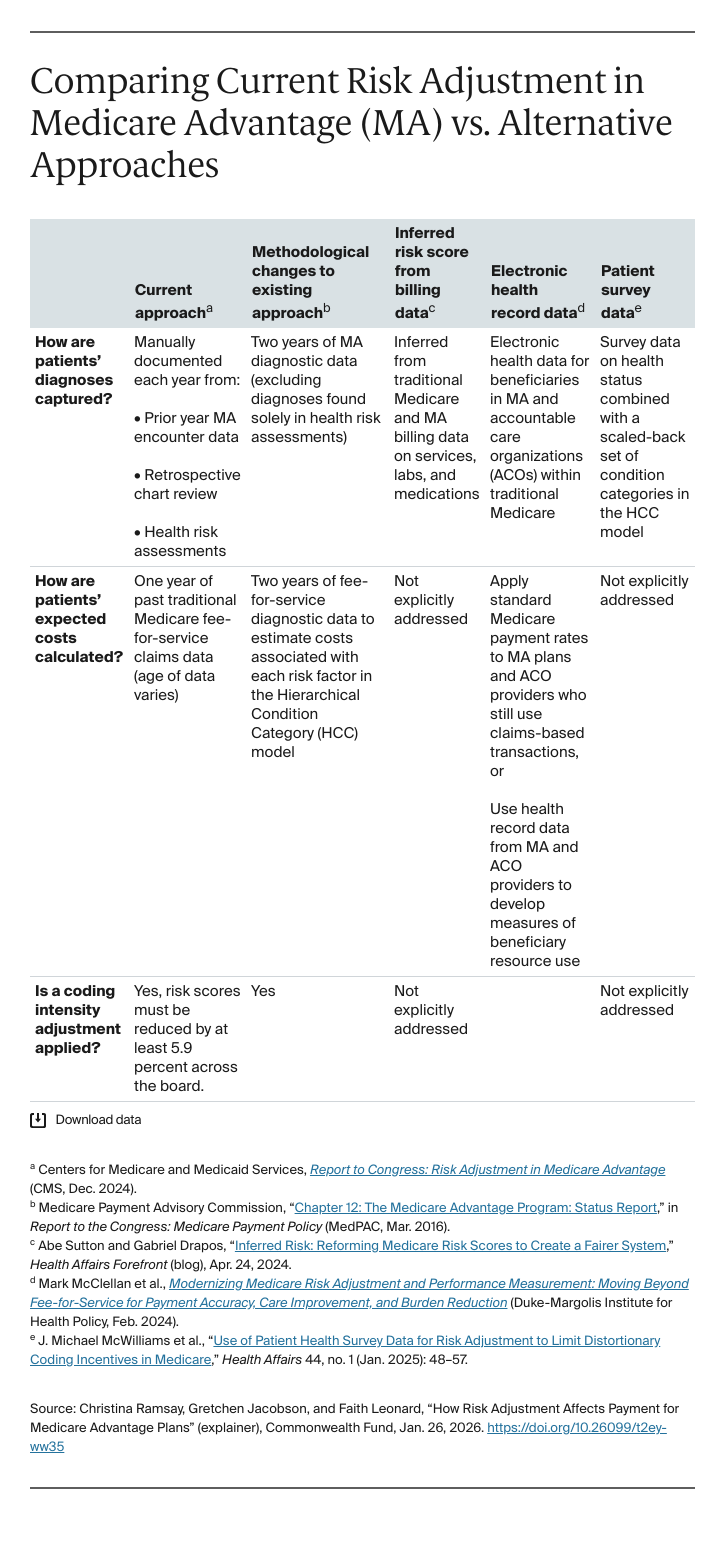

Researchers have proposed several policy options to address these data and coding issues. In 2016, MedPAC, an independent congressional agency that advises Congress on Medicare issues, recommended changes that would:

- Use two years — instead of one year — of diagnostic data from Medicare Advantage as well as traditional, fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, which would narrow differences in coding intensity and improve chronic condition coding for enrollees.

- Exclude diagnoses derived from health risk assessments from the HCC model, given that these codes are more common and varied in MA compared with traditional Medicare.

- Change the coding intensity adjustment to address any remaining coding differences between traditional Medicare and MA after making the two changes above.

Many have echoed support for these reforms, while some also suggested setting a threshold level of coding and auditing plans that exceed it.

Other policy experts, however, have proposed more fundamental shifts in the data sources and processes used for capturing patients’ diagnoses.

Use CMS billing data. Last year, Abe Sutton (now head of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, part of CMS) and Gabriel Drapos proposed testing a new approach to establishing patient risk scores. Rather than rely on manual documentation by plans and providers, CMS could infer patients’ diagnoses based on all its billing data on past services, labs, and medications for all traditional Medicare and MA beneficiaries. From this data, CMS could create “synthetic cohorts,” each representing a group of patients with similar characteristics and care utilization, to help set risk scores.

This approach, however, would likely create two issues for CMS. First, it could inflate payments to MA plans. If MA beneficiaries are compared to each other — rather than to traditional Medicare patients — using diagnostic, cost, and use data, the coding intensity adjustment would no longer be required. Removing this downward adjustment to risk scores would essentially result in an across-the-board increase in payments to all plans, creating higher spending for CMS.

Second, if CMS were to continue using fee-for-service claims data to determine the predicted costs of each risk factor, there might be a risk of perpetuating favorable selection issues between traditional Medicare and MA. In other words, because MA enrollees tend to have lower spending than similar beneficiaries in traditional Medicare, basing MA payments on fee-for-service costs would continue to overestimate MA enrollee costs.

Use electronic health record data. Experts at the Duke-Margolis Institute for Health Policy have proposed using electronic health record data from beneficiaries enrolled in MA and accountable care organizations (ACOs), which are care delivery models within traditional Medicare that also use risk adjustment to determine payment. Compared with enrollees in fee-for-service Medicare, these MA and ACO enrollees may show more similar use patterns and costs and serve as a better basis for calculating payment.

Use patient survey data. Experts at Harvard University have proposed a hybrid risk score partially drawn from survey data on enrollees’ health status, which would be less subject to manipulation by plans and providers than claims-based diagnoses. Their approach, which couples health status data with a scaled-back set of HCCs, might better align payments to enrollee health.

What are the implications of risk adjustment reforms for MA plans and taxpayers?

Risk adjustment was instituted in Medicare Advantage to ensure that plans are not financially deterred from enrolling and caring for patients with more costly health needs. However, the current risk adjustment model’s shortcomings — such as suboptimal data and the opportunity for overcoding — contribute to billions more in yearly plan payments. By addressing these shortcomings, reforms could potentially save taxpayer dollars and ensure resources are efficiently spent toward beneficiaries who most need them.