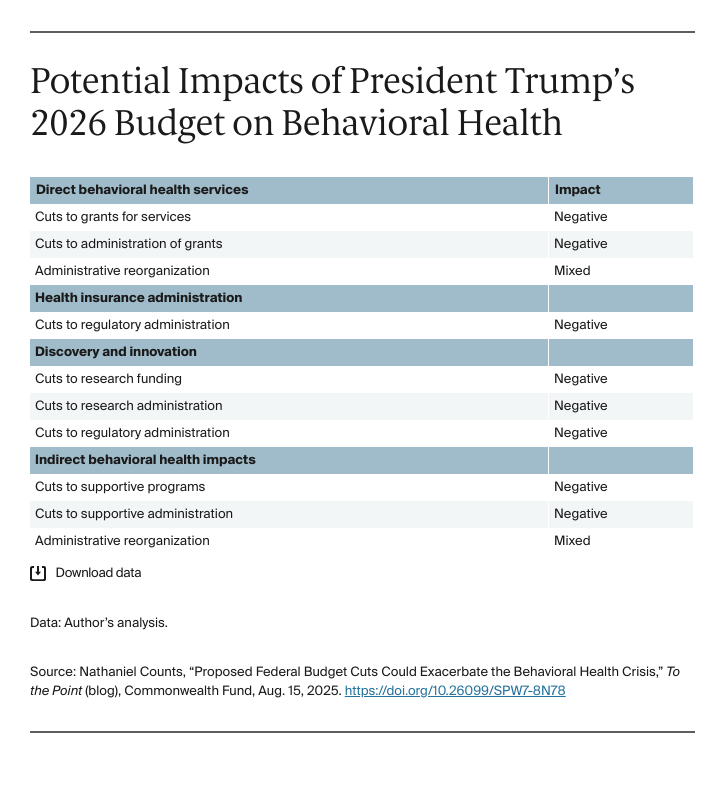

President Trump’s proposed 2026 budget requested $31 billion in cuts to the discretionary budget for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). These cuts would affect HHS grant programs and administrative functions, but exclude so-called “mandatory” spending at HHS, like Medicaid and Medicare. H.R. 1, however, will have an impact on mandatory spending by cutting Medicaid. The cuts to grant funds would magnify Medicaid losses, leaving even fewer resources for community-based providers and causing many to shut down.

The President’s budget also proposed reorganizations, including creating a new Administration for a Healthy America (AHA). The AHA would combine a range of agencies, including those focused on behavioral health, such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and some programs at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). These reorganizations also interact with other priorities, such as an executive order (Ending Crime and Disorder on America’s Streets) to deprioritize evidence-based strategies for helping unhoused people with mental illnesses access housing.

The final budget may not align with the President’s proposal, as Congress still needs to pass the budget into law. The effects of the budget, if passed as proposed, are outlined below. (Note: the specific programs cut and the size of those cuts are difficult to accurately determine.)

Cuts to behavioral health grants threaten access to lifesaving care. The proposed budget would cut spending on mental health and substance use block grants, along with an array of other behavioral health grant programs, eliminating some entirely. Many of the community-based organizations that receive these funds rely on these grants to provide care; cuts will lead to loss of services. As a result, some people will lose access to the services they need. Similarly, less funding for administrative functions may lead to delays in funding or less effective program management.

The proposed budget also combines many behavioral health grants into large block grants within the AHA. For some community-based organizations, the new block grants may promote efficiency because they can seek more funding from a single source. Community-based organizations that serve the needs of specific target populations may be deprioritized in a larger block grant though, leading to gaps. For example, current grants set aside funds to focus on the needs of adolescents and young adults at risk of developing serious mental illnesses. The grant funds allowed for effective outreach to this group and to provide specialized services that not only attend to their behavioral health needs but also connect them with education and training supports. Without the funds specifically earmarked, organizations that serve adolescents and young adults may not get these needed resources, and the population could suffer worse outcomes.

Cuts to oversight agencies may affect access to behavioral health services in health insurance. The proposed budget would cut spending at CMS and the Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA) in the U.S. Department of Labor. CMS and EBSA play important roles in ensuring that people receive coverage and benefits under commercial insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare. This includes upholding important policies like the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act and Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Cuts to administration in these agencies may lead to gaps in coverage and access.

Cuts will impact discovery and innovation. The proposed budget would cut grant spending and administration at the National Institutes of Health, as well as CDC. Both agencies play key roles in researching effective behavioral health treatments, including therapeutics, models of care, and digital innovations. Cuts will surely slow the U.S.’s progress in these areas. Similarly, cuts to service grants will stifle innovation in communities across the nation. For example, grants to community-based peer-support organizations allowed for local innovations across the country, testing new models of care and building an evidence base for critical strategies. One example is using peer-support specialists to promote successful transitions from inpatient care to community services for people that have experienced behavioral health crises. Today, these peer-support services are an increasingly established part of the behavioral health care system and were made possible by federal grant funds.

Cuts to the Food and Drug Administration, CMS, and SAMHSA will slow the translation of innovative treatments into practice. For example, virtual reality–based behavioral health treatments hold promise for a range of conditions including schizophrenia but need interagency coordination to promote appropriate access. Without proper staffing, these agencies will not be able to ensure that people get access to safe and effective interventions.

Cuts to other supportive programs. People rely on a range of federally funded programs for their well-being, including programs that support people with disabilities to live in the community or allow access to high-quality childcare. The proposed cuts may reduce access to these key supports, putting people at risk of worse behavioral health outcomes and possibly greater disability. However, the reorganization under the AHA could mitigate some of this risk, if it is able to better coordinate programs or achieve greater efficiency.

Conclusion

Cutting grants and administrative functions that affect access to effective behavioral health care and reorganizing agencies on which communities depend will have far-ranging and mostly harmful effects. With a national behavioral health crisis that continues to worsen, this country demands and deserves a budget that meets the needs of the moment.