In December, ACIP voted to remove the recommendation that all babies receive a hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth, instead recommending parents confer with a provider about when to vaccinate. Many clinicians, epidemiologists, and researchers have criticized the recent changes ACIP has made — most vociferously, the removal of the hepatitis B birth dose recommendation — as representing a fundamental departure from rigorous scientific inquiry that will cause preventable disease and patient harm. Meanwhile, USPSTF — which makes recommendations for a range of preventive services, including cancer screenings, drug and alcohol use counseling, and HIV screening and preventive medication — has not met since last March amid news reports that the Secretary may fire its members.

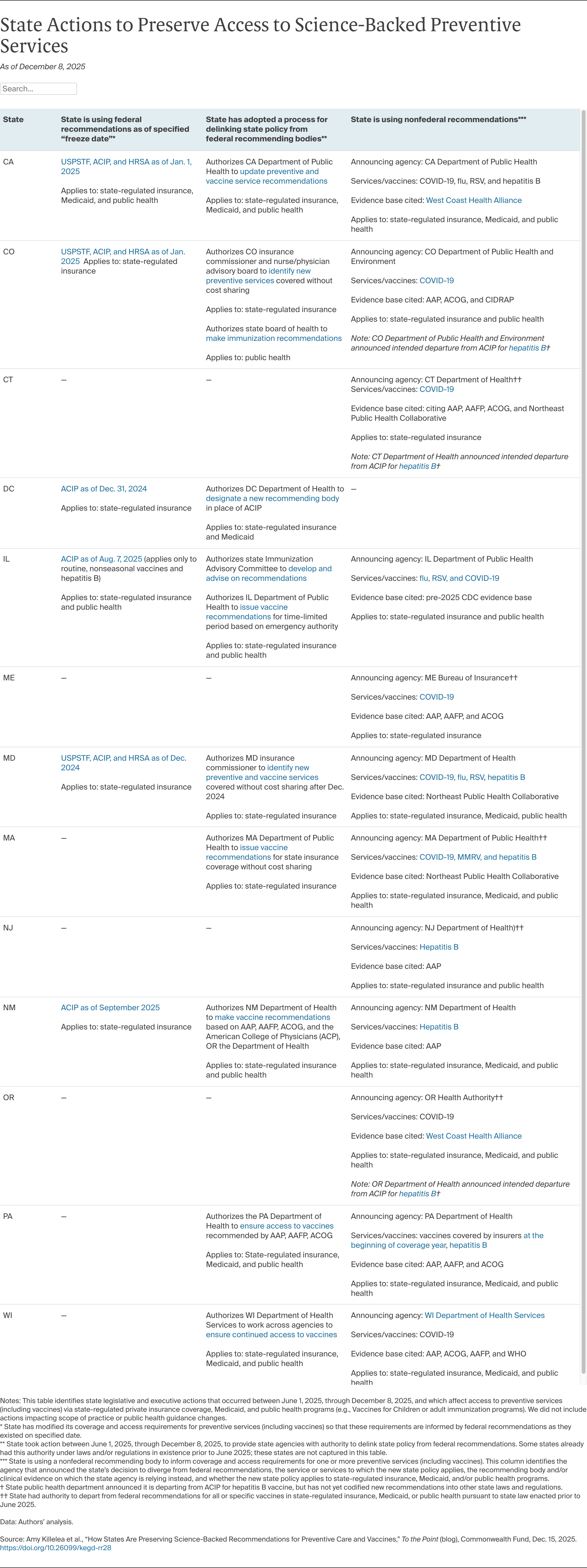

These developments have prompted states to preserve scientifically backed services where they can: state-regulated private insurance plans, Medicaid, and public health programs. State policymakers must determine how to move away from federal recommending bodies without further damaging trust in public health.

Should states declare federal recommendations no longer credible?

As the federal bodies change their processes and recommendations, states should use data and evidence to determine whether to continue following those recommendations or chart a new course. Some states have chosen the latter and moved to delink all of their coverage and public health standards from ACIP, while others have done so only for COVID-19. A more focused approach, zeroing in on specific services one at a time, may be simpler in the short term and buy states time to identify a new recommending body. However, deeming some of ACIP’s recommendations credible, but others not, risks confusion and may erode trust in all recommendations over time.

No state has yet announced its departure from USPSTF or HRSA recommendations, but some are laying the groundwork to do so if those bodies follow ACIP’s trajectory. For example, some states have opted to tie their coverage and public health requirements to the specific federal recommendations that were in place at the end of the Biden administration. This approach preserves the status quo in the short term. But these frozen-in-time recommendations can’t account for changes in science and will become obsolete. In addition, announcing a “freeze date” pegged to a prior administration runs the risk of further politicizing preventive services policy, especially if the reasons for doing so are not well communicated by policymakers or understood by the public.

What alternative clinical recommendations should states adopt?

If states stop using the federal recommending bodies, they must identify alternatives. Colorado, for instance, authorizes an existing health board to identify services to be covered without cost sharing if federal recommendations change, including for vaccines and preventive services currently recommended by USPSTF and HRSA. By identifying a health board with broad expertise and community connections to advise state health officials, the state may engender public trust in its recommendations. Other states have authorized regulators to unilaterally adopt different recommendations without specifying a process for evidence review and transparency. This approach facilitates quick action in an emergency, but may run into challenges when it comes to building public trust and provider buy-in.

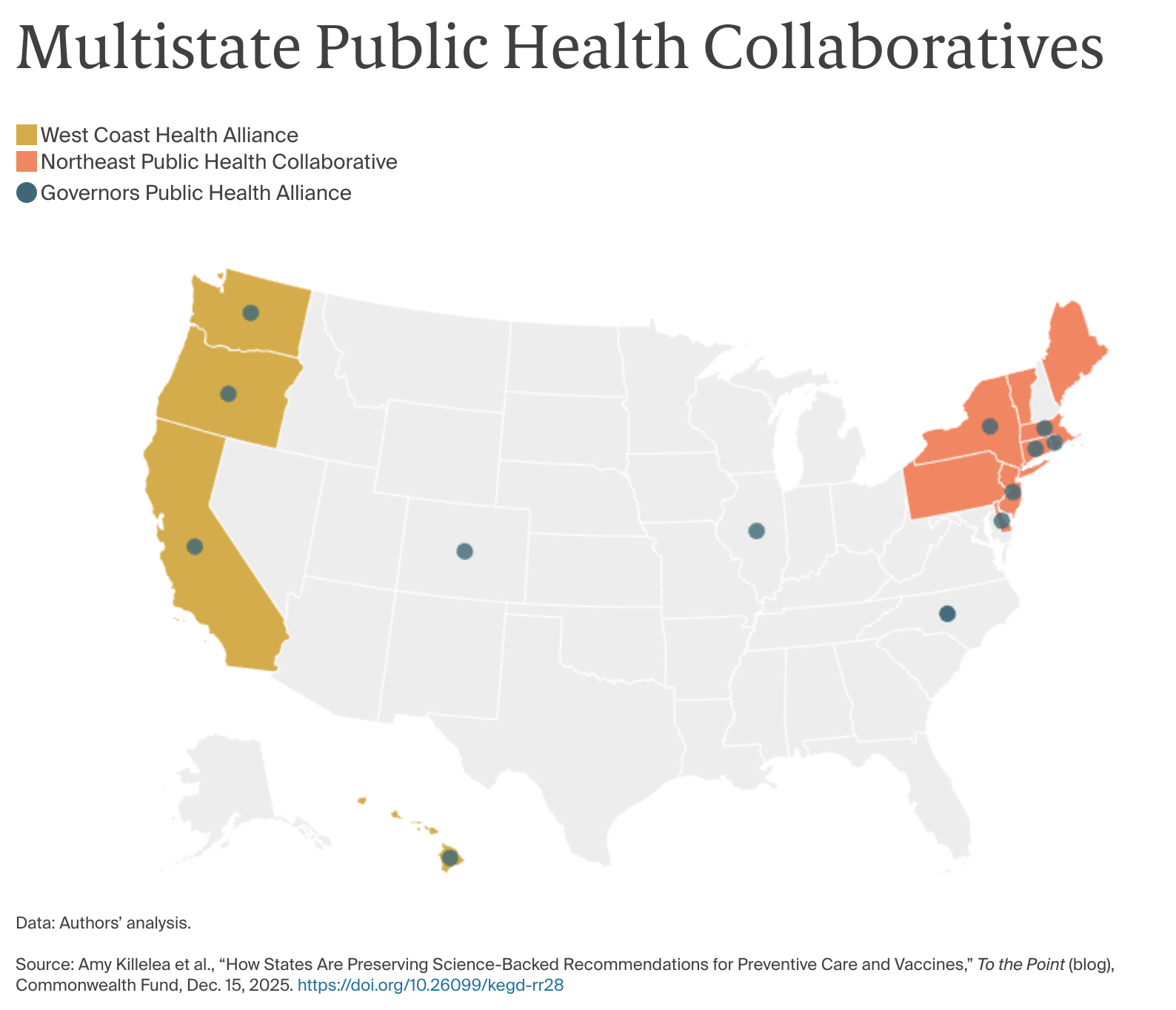

Still other states have formed regional collaboratives to develop vaccine recommendations and could use these bodies to implement regular, transparent reviews of clinical evidence on vaccines and other preventive services. Two prominent compacts — the West Coast Alliance and the Northeast Public Health Collaborative — have begun announcing vaccine recommendations, but are proceeding slowly and have provided limited information about the processes they will use to review evidence and make recommendations. So far, only Oregon has embedded the recommendations of its collaborative in state law, but as these compacts develop more transparent and intensive evidence review processes, more states may consider codifying reference to these collaboratives in state law. Meanwhile, a third collaborative has emerged — the Governors Public Health Alliance — to coordinate across regional compacts and states.